Simone Martini | Maestà del Palazzo Pubblico di Siena Maestà (Madonna with Angels and Saints) |

| Simone Martini’s Maestà, painted in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico in 1315-16, is a study in the careful synthesis of religious iconography and political intent. It was commissioned by the governing committee of Siena, Li Signori Nove Governatori e Difenditori del Comune e del Popolo di Siena (fortunately known as the Nine, or I Nove), who held power in Siena from 1292 until 1355. The Maestà was painted within a few years of the completion of the Palazzo Pubblico itself, and was probably the first work in an extensive program of pedagogical decoration which includes Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Allegories of Good and Bad Government, Taddeo di Bartolo’s frescoes in the Antechapel, and Martini’s later Guidoriccio da Fogliano at the Siege of Montemassi. |

|

||

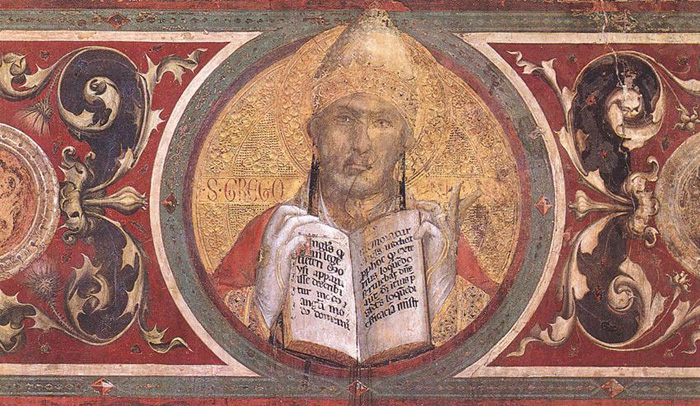

| Simone Martini, Maestà (Madonna with Angels and Saints), detail, the medallion representing St Gregory, 1312 - 1315, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena

|

||

An inscription runs under the fresco, a reassurance from the Virgin to her audience, that she will watch over Siena, on one condition:

|

||

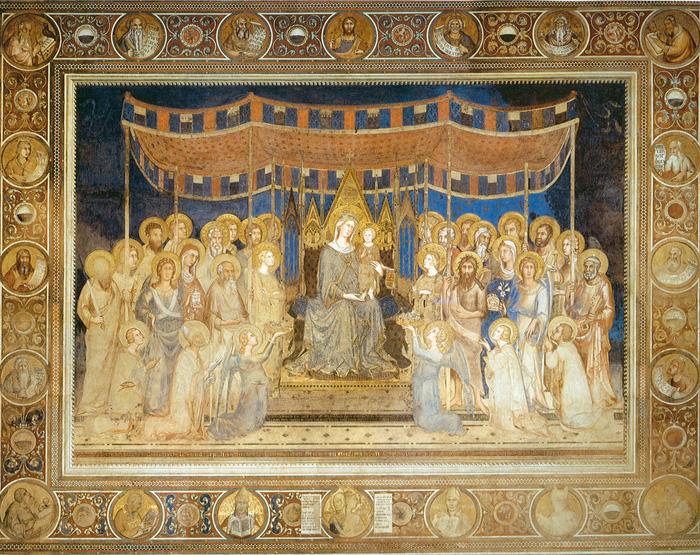

After the early works that have been attributed to him in a fairly plausible way, although purely on stylistic grounds, we come to a concrete element: the Maestà in the Palazzo Pubblico is the oldest painting that we can safely attribute to him. The end wall in the Sala del Mappamondo is entirely covered by this fresco. Surrounded by a frame decorated with twenty medallions depicting the Blessing Christ, the Prophets and the Evangelists (in the corners, each one with his symbol) and with smaller shields containing the coats-of-arms of Siena (the black and white standard) and the Sienese people (the lion rampant), the fresco shows a host of angels, Saints and Apostles, with the Madonna and Child in the centre. To the left of the splendidly decorated throne, Saints Catherine of Alexandria, John the Evangelist, Mary Magdalene, Archangel Gabriel and Paul; to the right, in almost identical positions, Barbara, John the Baptist, Agnes, Archangel Michael and Peter. Below, kneeling, are the four patron Saints of Siena: Ansano, Bishop Savino, Crescenzio and Vittore, accompanied by two angels who are offering Mary roses and lilies. The whole scene, set against a deep blue background, is surmounted by an imposing canopy of red silk, significantly held up by Saints Paul, John the Evangelist, John the Baptist and Peter. In the lower section of the fresco, on the inner frame, are the remains of an inscription which has been reconstructed as follows: "Mille trecento quindici era volto/ E Delia avia ogni bel fiore spinto/ Et Juno gia gridava: I' mi rivolto!/ Siena a man di Simone m'ha dipinto" (1315 was over and Delia had made the lovely flowers blossom, and Juno cried: I'm turning over. Siena had me painted by the hand of Simone). There is no doubt that the artist mentioned was indeed Martini, but the interpretation of the date is controversial: some think that it refers to June 1315, others believe that it means June the following year, for 1315 was over, Delia (Spring) had already made the flowers bloom, whereas Juno, to whom the month of June was dedicated, was about to show her second half.

|

||

Simone Martini, Maestà (Madonna with Angels and Saints), 1312 - 1315, fresco, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena

|

||

The most obvious innovations present in Simone's style, an art that was very different from traditional forms, are his ideas of three-dimensional space. The canopy's supporting poles are placed in perspective, thus giving a sense of depth to the composition. Under the canopy there is a crowd of thirty people: no more processions of people in parallel rows, but concrete spatial rhythms and animated gestures. Simone was quite clearly acquainted with the perspective constructions that Giotto had used in Assisi (see Guided Tour #3), an acquaintance that might have come to him through the work of the Master of Figline or that of Memmo di Filippuccio. But his art also contains a personal interpretation of elements of the French Gothic (not necessarily the result of a journey abroad, for he could have seen ivory carvings, miniatures and goldsmithery): the pointed arch structure of the throne, the precious ornamentation of the materials and the golden reflections give the whole scene a vaguely secular mood. But there is something more. Simone has developed a new way of understanding art: the wall is not simply painted, but carved, incised, set with coloured glass, raised surfaces, strong and bright colours. The various materials, like glass, tin and so on - everything that is not tempera or coloured earth - are all handled with great confidence by Simone. Simone Martini owes a great deal to the work of Sienese goldsmiths, the Gothic shapes and the sophisticated and shining surfaces were undoubtedly influenced by the artefacts produced in the workshops of goldsmith artisans, who decorated the most precious metals with the new technique of translucid enamels.

|

||

|

||

Simone Martini, Maestà, 1312 - 1315 (detail), affresco su parete, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena |

||

In 1321 Simone Martini and the assistants of his workshop restored the fresco, retouching some of the figures that had been damaged: the faces of the Virgin, the Child, the angels and the patron Saints, Ansano and Crescenzio.[2] The two different periods when Simone worked on the Maestà are very important in our reconstruction of the development of his art: the restored sections, with their more linear design and more transparent colours, are much more self-confident than the earlier parts. But let's not forget that between his first intervention and the second one Simone had been to Assisi. And that's not all. Tests carried out recently have shown that in the lower section (more or less at the height of the thighs of the kneeling Saints, about four metres from the floor) there is a clearly visible line where the colour tonality changes. Since it does not look simply like the demarcation between two different days' work, It was suggested that it indicates a short period of interruption on the work on the fresco. Therefore, we can say that even the first painting of the Maestà was carried out in two separate sessions. One can but wonder where Simone was while the host of Saints was waiting to be completed, and what superior power had distracted the artist from such an important fresco. He was probably in Assisi, measuring the wall surfaces of the chapel of San Martino, planning the scenes and perhaps even drawing his first synopias on the walls. The glorification of the Virgin is the iconographical element on which the painting is based: Mary's function is to protect the city, and the four patron Saints are her intermediaries. The fresco was painted in the room where the government held its meetings to discuss the future of the city: the Nine are the highest representatives of the citizenry and the Madonna's protection must first of all cover them. Political messages in depictions of holy scenes were not a novelty for the Sienese; Duccio's Maestà, carried in triumph into the Cathedral in 1311, includes both the patron Saints and a prayer to the Virgin; although in a more veiled way, its purpose was the same. But in Simone's the civic and secular content is developed fully: the sacred elements are included in a slightly ambiguous dimension, in which the heavenly court becomes the highest exaltation of a very worldly and real court. Simone's social ideals, "courtly" and aristocratic, are the same as those of his clients: the Maestà is both sacred and profane and the courtly gestures of the characters reflect a noble and elitist vision of religion.[°] |

||

|

||

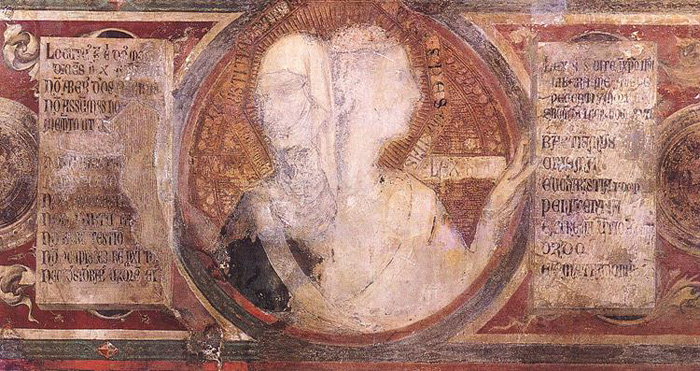

Simone Martini, Maestà, the medallion representing the Allegory of the Old and New Law, 1312 - 1315, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena |

||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

[1] Biografia di Simone Martini | It is convenient to think of Simone Martini (b. 1280/85, Siena, d. 1344, Avignon) as a pupil of Duccio, although nothing is known of Simone's life before 1315. From this point on, however, its main outlines are reasonably clear. He spent much of his life in Siena and Tuscany. He may have visited Naples c. 1317 and he certainly visited Avignon c. 1314, staying there until his death in 1344. At least one other visit to Avignon had probably already taken place. If one were to reconstruct the life of Simone Martini using only documented facts one would have a very short account, with a great many gaps. However, making use of many of the elements that have been handed down by traditional accounts, we shall be able to reconstruct the great artist's life story. Let us begin this short historical and chronological account from the date of Simone's death, which we know for certain as 4 August 1344. If we are to believe Vasari, who tells us that on Simone's tomb there was an epitaph stating that he had died at the age of sixty, then the artist must have been born around 1284. What did Simone look like? He was probably not a very handsome man, at least according to Petrarch, who was a close friend of his. Some scholars claim that the Christ before Pilate on the back of Duccio's Maestà in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena is a portrait of Simone; others believe that he is the knight with the blue hat who is witnessing, half amused, half in disbelief, the Miracle of the Resurrected Child in the Chapel of San Martino in the Lower Church of San Francesco in Assisi. He may have been born in Siena, in the neighbourhood of Sant'Egidio; or perhaps, according to another theory, he was born in the countryside around Siena, near San Gimignano, the son of a Master Martino specialized in the preparation of the arriccio (or first coat) applied to wall surfaces to be frescoed. Simone most probably learnt the trade in the workshop of Duccio di Buoninsegna, but he only became well-known as an artist when he painted and signed the Maestà in the Sala del Mappamondo in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena in 1315. If we consider that the Comune of Siena chose Simone as the artist to paint such an important fresco, we can assume that he must already have had quite a good reputation before he was commissioned the Maestà. Working for the Comune on the decoration of the Palazzo Pubblico, the heart of the city both literally and symbolically, was an experience shared by all those who are today considered the greatest Sienese painters of the late l3th century and the first half of the l4th: Duccio, Simone and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. From the reconstruction of Martini's life and work, it appears that he travelled frequently from Siena to Assisi and viceversa. It seems that between 1312 and 1315 he did the drawings for the stained-glass windows in the Chapel of San Martino in the Lower Church in Assisi, for these windows certainly look earlier and more archaic from a stylistic point of view than the frescoes in the same chapel (finished by 1317). In 1315 he painted the Maestà in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena and probably also did some more work in Assisi, on the frescoes in the Chapel of San Martino. Also in 1315, as a result of the canonization of Louis of Toulouse, Simone probably received the commission for the Naples Altarpiece, a signed painting which is traditionally supposed to have been painted in Naples, although there is no evidence to support this theory. Based on a document in which Simone is not referred to as a painter, but as a "miles," a term used in the Middle Ages to mean a knight, Simone must have been knighted for having paid tribute to King Robert, his family and the French royal lineage both in the frescoes in Assisi and in the Naples Altarpiece. It was fairly common procedure in the late Middle Ages for a sovereign to knight an artist for such merits. A large and quite varied group of panel paintings is normally dated around the late 1310s and the early 1320s. Our documentation on this group of paintings is so scarce that we know for certain the dates of only two of them: the polyptych for the church of Santa Caterina in Pisa (1319) and the one in the Museum at Orvieto (1320). As far as the others are concerned, especially the numerous polyptychs produced in the Orvieto workshop, most recent scholars tend to date them at the early 1320s, but entirely on stylistic grounds, for there is no documentary evidence at all. In any case, an accurate study of Simone's production in Orvieto is extremely difficult, for all the paintings attributed to him show quite considerable interventions by assistants. All through the 1320s the Biccherna registers (the Comune of Siena's accounting ledgers) record payments to Martini, evidence that he must have worked a great deal in Siena before leaving for Avignon. These documents refer to a variety of paintings, many of which have not been identified or have not survived. In 1321 Simone was paid to restore his own Maestà, which had been damaged already by rainwater infiltrations in the wall, and for the work he had done on a painted Crucifix (which was eventually completed by his pupil, Cino di Mino Ughi). In 1324 he married Giovanna, the daughter of Memmo di Filippuccio and the sister of Lippo Memmi. Simone may have been a rich man, for his activity as a painter certainly provided him with a substantial revenue. Shortly before his marriage, in January or February 1324, he bought a house from his future father-in-law and presented to his wife-to-be a generous wedding gift. Perhaps with an excess of sentimentalism, this gift has been interpreted as a sign of gratitude: after all, Simone was already past forty and not very handsome, so he was grateful to the young girl for accepting to marry him. Whatever the truth may be, the gift is undoubtedly evidence of his generosity, a trait that comes across quite clearly in his last will and testament as well. Simone married into Lippo's family, then, and this further strengthened a bond of friendship and artistic collaboration that lasted throughout their careers, reaching its highpoint in the Annunciation in the Uffizi where it is actually quite difficult to distinguish Simone's work from Lippo's. Also presumably dating from the 1320s are the Altarpiece of the Blessed Agostino Novello and the small tempera portrayal of St Ladislaus, King of Hungary. In 1326 Simone must have painted a panel for the Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo: we know this must have been a very important painting, both because of the huge sum of money he was paid for it and because Ghiberti, in his l5th-century Commentaries, described it as "molto buona," and we know that Ghiberti was never a great admirer of Simone's, since he thought Ambrogio Lorenzetti was a better painter. The following year Simone painted two banners which have not survived; they were presented by the Comune of Siena to Duke Charles of Calabria, the son of Robert of Anjou. In 1329/30 he painted "two little angels on the altar of the Nine" in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena and a portrayal of the rebel Marco Regoli (who was hanged by his feet, a form of execution reserved for traitors and forgers) in the Sala del Concistoro; neither of these frescoes has survived. Also in 1330 Simone painted in the Palazzo Pubblico one of his most celebrated works, the fresco of Guidoriccio da Fogliano, a commemoration of the conquest of the castle of Montemassi in 1328 (the date, "MCCCXXVIII," under the fresco refers to the conquest and not to the fresco). The recent discovery of another fresco below this one depicting a similar scene, has raised some doubts as to the attribution. The history behind the Guidoriccio, its meaning and iconography, have been the object of a very animated debate amongst the most authoritative art historians. The date 1333 appears on the frame of the Annunciation painted for Siena Cathedral: this is the last painting we know of that Simone worked on before moving to France. The primary consequence of the Papal See being transferred to Avignon in the early l4th century was that it transformed that small Provencal city into an artistic centre of European renown: paintings, artists and entire workshops, incentivated primarily by the Italian cardinals, were transferred to Avignon, and Simone, too, moved there in 1336. In what became the busiest art centre of the century, the style of the northern artists soon blended with the aristocratic elegance of Italian painting, especially the art of Simone, laying the foundations for the International Gothic style, an art of exquisite courtly refinement, of which Simone is generally considered a forerunner. Although a member of a very stratified society (common citizens, imperial power and feudal hierarchy, the Pope and the Papal State), Simone was always associated with the highest social levels. His career evolved from one important commission to the next, always at the service of the highest powers. While in Siena he worked for the Government of the Nine, decorating the palace where they held their meetings; then he worked in the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi, the most important institution of the Franciscan Order, but one which was temporal enough to be influenced by the current political situation. Then he gained the favour of the House of Anjou working at the Court of King Robert; and lastly he moved to Avignon to work for the most powerful members of the Church. From local painter to artist of European renown: his art went from secular subjects commissioned by the city's lay government, to holy subjects painted for Church patrons and even for royalty. But he always remained faithful to his style, an elegant, realistic and cultured art. His growing reputation as an artist must also have contributed to the general esteem he was held in, and we find his name appearing in documents in roles that required public trust. These are all incidents that have nothing to do with his career as a painter, but they help us reconstruct his life history and his temperament. The contrasting opinion of scholars on Simone's later works is the result of the lack of information available. Apart from the fragments of frescoes in Notre-Dame-des-Doms in Avignon, all that has survived from this period is the frontispiece of Petrarch's copy of Virgil (now in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan), the Holy Family in the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, dated 1342 and the polyptych of Stories from the Passion now belonging to the museums of Antwerp, Paris and Berlin. Simone Martini died in Avignon in the summer of 1344. As Vasari tells us "he was overcome by a very serious infirmity. . . and not being able to withstand the gravity of the illness, he passed away." Clearly Simone was already ill and must have been aware that the end was near, for on 30 June he had already drawn up a will. The true nature of Simone, an extremely generous man, deeply attached to his family, comes across from this document. And his family loved him as much as he loved them, especially his wife Giovanna who returned to Siena from Avignon in 1347 (perhaps she was escaping the Black Death) all dressed in black, still in full mourning for her beloved Simone. [2] Damage to the fresco over time was caused by the storage of salt in basement rooms beneath the fresco. Moisture carried the salt up through the inner walls of the building and caused crystals to form beneath the surface of the paint. These pushed the pigment forward and damaged the structural integrity of the plaster.[°] |

||||

Montefalco |

Perugia |

Siena, Duomo |

||

|

||||

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia article Maestà (Simone Martini) published under the GNU Free Documentation License and from Art of Simone Martini, published on www.wga.hu. |

||||

Travel guide for tuscany | Art, history, hidden secrets and holiday houses in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia |

||||

Siena |

Podere Santa Pia, giardino |

Podere Santa Pia |

||

|

||||

Val d'Orcia" between Montalcino, Pienza and San Quirico d’Orcia. |

Siena, Piazza del Campo |

Orvieto, Duomo |

||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, situated in a particularly scenic valley, which overlooks on the hills around Scansano, the Valle d'Ombrone, the sea and Monte Christo |

||||

| Palazzo Pubblico in Siena |

||||

| Known also as Palazzo Comunale, Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico is considered one of the finest examples of gothic secular architecture. Formerly the residence of the city’s Signoria, or Podestà, the building is now the seat of the town council. Of all the buildings that look onto Piazza del Campo, the Palazzo Pubblico is the most imposing and stands as the natural centre of the square’s architectural perspective. The building is made of stone on the lower level and red brick on the upper levels and is crenellated at the top edges. One of the most pleasing aspects of the structure is its subtly concaved shape which is designed to complement the shape of the Piazza del Campo. The Palazzo Pubblico, whose construction began in the 13th century, houses the city's Civic Museum. Access to the Museo Civico, the city museum of Siena, is from the superbly proportioned gothic courtyard of the Palazzo Pubblico. Founded in the 1930s, the Museo Civico contains some of the finest paintings, sculptures and frescoes of the renowned Senese School. Two flights of stairs lead up to the Sale Monumentali grand chambers of the museum. Immediately to the right is the Sala del Mappamondo, formerly used as the meeting room for the General Council of the Republic of Siena. The room takes its name after a rotating map, now lost, painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, that showed the lands governed by the city. On the far wall of the chamber is a Maestà fresco by Simone Martini, painted between 1312 and 1315, still striking today on account of its delicate use of the chromatic palette and its purity of lines. This is regarded as being the first real masterpiece by Simone Martini, who in 1328 also painted the portrait of the condottiero Guidoriccio da Fogliano, who seized the Castle of Montemassi. On from the Sala del Mappamondo, the magnificent Sala dei Nove was used as a meeting chamber for the town’s Governo dei Nove government of nine councillors. Over the centuries this room has changed name a number of times, from Sala delle Balestre when it was used as an armoury to Sala della Pace from an allegorical figure of Peace in the decorations. In 1337 Ambrogio Lorenzetti was commissioned to decorate the room with a cycle of frescoes known as the Allegory of Good and Bad Government. The largest secular painting cycle of the Middle Ages, this work is a political manifesto in which the painter has depicted two opposing methods of government along with their consequences. To the left of the Sala del Mappamondo is the so-called Anticappella, once used as an antechamber of offices for the Concistoro. In 1415 Taddeo di Bartolo was commissioned to decorate it with a cycle of frescoes depicting The Virtues of Illustrious Gods and Men. A fine 15th century railing designed by Jacopo della Quercia encloses the Chapel. Completed at the end of the 15th century, when the population of the city was on the rise, this railing is larger than its counterpart on the ground floor of the building. In 1407 Taddeo di Bartolo was commissioned to decorate the room with his Storie della Madonna cycle of frescoes depicting episodes from the life of the Virgin. The adjacent passageway, known also as the Sala dei Cardinali leads to the Sala del Concistoro, with an internal doorway in marble by Bernardo Rossellino. The brightly coloured frescoes on the ceiling were completed between 1529 and 1535 by Domenico Beccafumi, once more a representation of themes related to justice and patriotic devotion that take their cue from the Lorenzetti Good Government and the di Bartolo Illustrious Men cycles. Next to the Sala del Concistoro is the Sala di Balia, also known as Sala dei Priori. This room is adorned with frescoes by Spinello Aretino (1407) illustrating the Life of Pope Alexander III dei Bandinelli. The Sala del Risorgimento, known also as the Sala di Vittorio Emanuele II, was inaugurated in 1890. The walls are decorated with frescoes of episodes from the Unification of Italy, painted by late-19th century Senese artists. The upper floor opens onto a large loggia, which overlooks the southern prospect of Siena. A number of adjacent rooms were reopened recently and contain the Quadreria, a collection of detached frescoes, paintings on wood and canvases both of the Senese School and by artists across Italy and abroad. Arte in Toscana | Ambrogio Lorenzetti | Allegoria ed Effetti del Buono e del Cattivo Governo Il Museo Civico di Siena Piazza del Campo, 1 53100 – Siena Opening hours 1 novembre - 15 marzo 10.00 - 18.30 16 marzo – 31 ottobre 10.00 - 19.00 |

Siena, Piazza del Campo e Palazzo Publicco Siena, Piazza del Campo e Palazzo Publicco Simone Martini, Guidoriccio da Fogliano all'assedio di Montemassi, 1328-30, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena

|

|||

|

||||