|

|

Lo Scheggia, Childbirth tray (desco da parto) with the Triumph of Fame (recto, detail), 1448–49, tempera, silver, and gold on panel, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Lo Scheggia |

| Giovanni di Ser Giovanni Guidi, known as Lo Scheggia, was the younger brother of Masaccio. 'Born in 1406 in San Giovanni Valdarno, Giovanni was the son of a notary, whose name he took, and of Monna Jacopa. He was also the younger brother of Masaccio (1401-1428), a much more famous painter one of the great innovators of Florentine Renaissance art, along with Brunelleschi and Donatello. His grandfather Mone, who was a cassaio, that is a craftsman specialised in the construction of chests, had a decisive influence on Giovanni’s training and set him on the path to his artistic career, where he was to specialise prevalently in the decoration of domestic furnishings, such as wedding chests, birth trays, spalliera panels, strongboxes and headrests. Giovanni was nicknamed lo Scheggia (the splinter), on account of his slender build, but also probably because of the particular specialisation of his work, constantly in contact with wooden artefacts. After a period as a mercenary, he settled in Florence and between 1420-1421 entered the workshop ofBicci di Lorenzo, an artist still bound to outmoded, traditional stylistic features and insensitive both to the new perspective approaches and also to the more modern sophistication of the international Gothic. Consequently Giovanni moved on to the workshop of his brother Masaccio, with whom he lived in Via de’ Servi with their mother. In effect, Giovanni’s early activity is characterised by the marked influence of Masaccio, which led Giovanni to translate the forms into geometric terms (as in the small ancon with the Madonna and Child and Two Angels in the Museo Horne in Florence). In 1432 he registered in the Guild of Stonemasons and Carpenters and the following year in that of the Physicians and Apothecaries, which was the Guild the artists enrolled in, a sign that he was by this stage specialised in his profession as a decorator of interiors and domestic furnishings, collaborating with carpenters and inlayers. His work was considerably appreciated in the city, so much so that he received commissions even for Palazzo Medici, including a spalliera panel (lost) illustrating the joust of 1469, which was set above strongboxes and chests in the first-floor chamber of Lorenzo il Magnifico (Cavazzini 1999, p. 13). As a painter of sacred subjects, in altarpieces and large-scale wall paintings, lo Scheggia’s commissioners were instead largely located in the rural district, in particular the Valdarno. Between 1436 and 1440 he collaborated on the intarsia cupboardsforthe Sagrestia delle Messe in the Duomo. In the interim, after the death of his brother (1428), Giovanni turned his attention to those artists who had shown themselves to be the most gifted interpreters of Masaccio’s teaching, such as Beato Angelico, Domenico Veneziano and Filippo Lippi. Around 1449 he created his masterpiece, the birth tray for Lorenzo il Magnifico portraying the Triumph of Fame (New York, Metropolitan Museum). Dating to 1456-1457 is the only signed work by loScheggia: the fresco portraying the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian and Scenes from the Life of Saint Anthony Abbot in the oratory of San Lorenzo in San Giovanni Valdarno. It is around this work that the critics have reconstructed the corpus of the painter’s works, drawing partly on catalogues gathered under the conventional names, Master of the Cassone Adimari and Master of Fucecchio. Among the most important works referred to lo Scheggia are the so-called Cassone Adimari, or Adimari Wedding Chest, actually a spalliera panel (Florence, Accademia Gallery), the birth tray showing the Gioco del civettino and the curved panels portraying the Triumphs of Death, of Fame, of Love and of Eternity, now in Palazzo Davanzati (the latter originating from the Medici collections) and the altarpiece of the Madonna and Child with Saints Lazarus, Martha, Mary Magdalene and Sebastian originating from the Collegiate church of Fucecchio (now in the Museo Civico).'[1] |

|

||

| Lo Scheggia was the younger brother of Masaccio, the short-lived revolutionary artist of the early quattrocento in Florence. Scheggia, on the contrary, had a long, successful career and was particularly adept at the production of secular domestic objects. This salver was commissioned to celebrate the birth of Lorenzo de' Medici (1449–1492), de facto ruler of Florence from 1469 until his death, and is the largest and most elaborate surviving birth tray. Twenty-eight men on horseback are shown pledging allegiance to Fame, a beautiful winged woman who holds a sword and a statuette of Cupid as she stands atop a globe on an enormous pedestal. This scene, known as the Triumph of Fame and based on Boccaccio's Amorosa Visione (1342) and Petrarch's Trionfi (1354–74), clearly shows the dynastic ambitions of Piero de' Medici, Lorenzo's father, who commissioned the work and gave it to his wife Lucrezia Tornabuoni. The tray must have had considerable commemorative value to Lorenzo, as it was hanging in his bedchamber at the time of his death. The back of the salver, once resplendent with silver decoration that has now oxidized, is embellished with Piero de' Medici's emblem, a long-standing Medici family symbol of eternity, usually encircling three feathers in reference to the ostrich, associated with the Resurrection. The feathers, red, white, and green represent the three theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity. At the top are the coats of arms of the Medici and the Tornabuoni. To the left of the central feather are the eight red balls of the Medici, and to the right the rampant lion of the Tornabuoni.'[0] |

Childbirth tray (desco da parto) with the Triumph of Fame (recto) and Medici and Tornabuoni arms and devices (verso), 1448–49 |

|

|

||

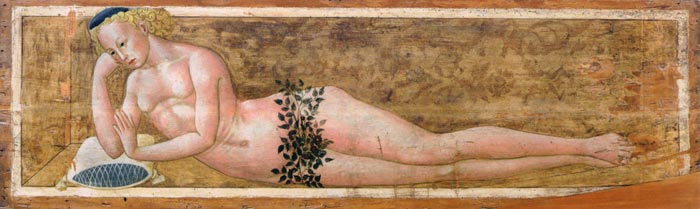

Reclining Youth |

||

|

||

Giovanni di Ser Giovanni, Lo Scheggia, Reclining Youth, Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon |

||

| Cassoni (wedding chests) were constructed by specialized carpenters who delivered them to the painters' workshop to be adorned with scenes on the front and side panels and often on the lids. The inside was often decorated with textile patterns and a male or female nude reclining in the entire length of the lid.

The picture shows the inner lid of a wedding chest with the image of a reclining youth. The female pendant of it is in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. This images of a private nature promoted fertility, the female nudes are notable predecessors of Titian's and Giorgione's naked Venus figures. |

||

|

||

Ameto's Discovery of the Nymphs |

||

|

||

Master of 1416 (Italian, Florentine, early 15th century), twelve-sided childbirth tray (desco da parto) with scenes from Boccaccio's Commedia delle ninfe fiorentine: Ameto's Discovery of the Nymphs and Contest between the Shepherds Alcesto and Acaten, ca. 1410, The Metropolitan Museum, New York |

||

The Master of 1416 is the name given to the painter of an altarpiece of the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints, dated 1416, in the Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence. |

||

|

||

Frederick III and Leonora of Portugal in Rome |

||

|

||

Giovanni di Ser Giovanni, Lo Scheggia (1406–1486), Frederick III and Leonora of Portugal in Rome, 1452, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts |

||

In 1452, the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick III, visited Italy to marry Leonora of Portugal and be crowned. At the left, in front of old St. Peter's in Rome, the pope crowns the kneeling emperor. In the center, the imperial procession makes its way through the city. At the right, Frederick III knights his brother on the Ponte Sant'Angelo. This chest is unusual because it depicts contemporary political events. Smaller panels originally decorated the ends of the cassone (and were in the same positions as installed here). They show the Empress Leonora returning to her palace, and Frederick III riding through Rome after his coronation. On the sides of the pedestal: Leonora and Ladislaus Returning to the Vatican and Frederick III's Procession through Rome. 'The Sienese provenance of this cassone may not be accidental, as four spalliera panels by the artist are in the Pinacoteca Nazionale there. |

||

|

||

Giovanni di Ser Giovanni, Lo Scheggia (1406–1486), Frederick III and Leonora of Portugal in Rome, (detail), 1452, |

||

|

||

[3] The panel The Story of Lionora de' Bardi and Ippolito Buondelmonte was attributed to the Master of Fucecchio in 1975. On the basis of illustrations, and noting the condition of the panel, Everett Fahy very tentatively points to compositional similarities with works by Domenico di Michelino, including the Story of Susanna at Avignon and the cassone front with the Triumph of Love and Chastity, sold at Sotheby's, New York, 26 January 2006. |

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Siena, Piazza del Campo |

Florence, San Miniato al Monte |

||

Pienza |

Bagni San Filippo |

San Quirico d'Orcia |

||

Florence, Duomo |

Orvieto, Duomo |

Monte Christo, evening sunset |

||

| Boasting Etruscan origins and having then developed as a Roman colony with the name Florentia, today Florence is a charming city attracting every year thousands of tourists, fascinated by the Cathedral, the Baptistery, the church of San Marco, San Miniato al Monte, Ponte Vecchio, Piazza della Signoria and Palazzo Vecchio, the Loggia dei Lanzi and its statues and many other famous monuments. The many Medicean villas scattered in the countryside surrounding Florence and Fiesole, with its Roman amphitheatre and the magnificent view of the Tuscan main city, are two fundamental stops while visiting Florence. To those who love historical commemorations and folklore, Florence offers various events in the course of the year: the Cavalcata dei Magi (evoking the trip the Three Wise Men did in order to give their presents to Jesus) in January, the Calcio in costume (football as it was played in the Middle Ages) in June and the Scoppio del carro (explosion of the cart) on Easter Day. Florence is also synonym with haute couture, with the various Pitti Immagine events, shopping, handicraft and good cuisine, thanks to its restaurants and the numerous trattorias in the historical centre, where to taste the dishes of Tuscan culinary tradition sipping some Chianti wine. Paganico, near Podere Santa Pia offers an excellent bus connection to the city. The Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence | A multitude of artists, including Arnolfo di Cambio and Filippo Brunelleschi, worked for 140 years - from 1296 to 1436 - to the construction of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, the Duomo of Florence. A must-see for all of the tourists who visit the capital of Tucany, the Duomo stands in an area completely closed to motor vehicles. One of the biggest churches in Europe, the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore boasts two stunning records: its renowned cupola, the fruit of Brunelleschi`s talent, is the biggest masonry dome ever built; moreover, thanks to Vasari and Zuccari, it features the broadest frescoed surface in the world. And if that is not enough, next to the cathedral Giotto`s bell tower (which is about 85 metres tall) commands the houses, palaces, historic residences and villas of Florence. Close to the cathedral stands the Baptistery of San Giovanni, an octagonal building dating back to the 4th-5th centuries whose walls are decorated with superlative mosaics and whose three doors are embellished with wonderful panels by Andrea Pisano and Ghiberti. So if you are planning your next holidays and you would like to admire Brunelleschi`s dome, Giotto`s bell tower and the baptistery from the balcony or the windows of your apartment in Florence, you had better look for a holiday house in the "Quartiere 1" (district 1), that is, Florence historic centre. Last but not least: after having visited these three masterpieces, you should visit the Museo dell`opera del Duomo as well. Art in Tuscany | Florence Firenze Art in Tuscany | The Duomo or Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence At a short distance from the Duomo, the Basilica of San Lorenzo was the official church of the Medicis. Not only did the membres of this influential family contribute to the construction of the building that tourists can still admire today; they chose it as their mausoleum: indeed, the mortal remains of the grand dukes of Tuscany and of their relatives lie in the so-called Medici Chapels. Going on towards the river Arno, you arrive at the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella. With its green and white marble façade, it was designed by Leon Battista Alberti. The church houses works by Giotto, Brunelleschi, Masaccio, Paolo Uccello, Giambologna... Crossing the river, you arrive in the district called Oltrarno, where the road begins to rise towards Piazzale Michelangelo. Over the upper-class houses and apartments emerges the Basilica of San Miniato al Monte. At the end of your tour, go down from Piazzale Michelangelo, cross the river again and go towards the Basilica of Santa Croce, or the "tempio dell`Itale glorie" (the temple of Italian celebrities), as Foscolo called it, where you can find the tombs of Michelangelo, Galilei, Alfieri... |

||||