| |

|

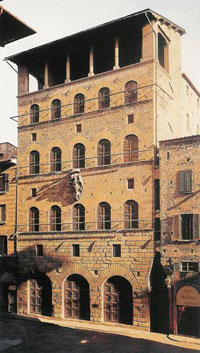

The Palazzo Davanzati is one of the oldest palaces in Florence, dating back to the early part of the 14th century.

The palace was originally owned by the Davizzi, a family of prosperous wool merchants, but was bought by the Davanzati family, in 1578. It is the latter’s enormous coat of arms, which looks so out of place on the facade.

In the years between 1400 and 1600 Italians became the most extravagant builders in Europe. Wealthy citizens commissioned magnificent palaces, and displayed their gentility and education through splendid possessions. Prestigious artists would produce domestic objects as well as paintings and sculpture. Social, cultural and moral messages could be found in a portrait or an inkstand.

The Renaissance was a period of profound change. Its revival of classical antiquity took place in a world of economic growth, scientific and geographical discovery, political and religious conflict. While reflecting these upheavals, domestic life also played an active role in the creation of art and culture.

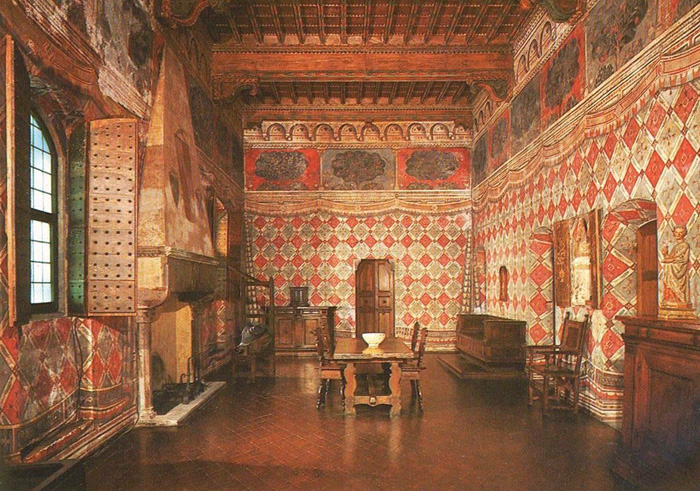

In the Early Renaissance this was not the only purpose paintings served. The walls of palaces were decorated in fresco, and their rooms were filled with painted furniture. Comparatively few of these secular frescoes have been preserved. Taste in the fifteenth century changed rapidly (almost as rapidly as it does today), and when the decoration of a room appeared old-fashioned, it was commonly superseded by a decorative scheme that looked more up-to-date. In Florence and in its neighborhood Gothic secular frescoes can never have proliferated as they did at the courts of Northern Italy, but a few examples survive to show the type of decoration that was employed. In the Palazzo Davanzati in Florence, for example, one of the large reception rooms is decorated with fictive wall hangings painted as though suspended from hooks in the molding above them, and at the top is a frieze divided by little colonnettes with vases of flowers between which runs a landscape with carefully rendered shrubs and trees.[1]

Palazzo Davanzati is a unique example of a transitional period of domestic architecture in Florence. It combines some safety and layout features of the late medieval tower home with some of the ideals that developed in the 15th century home. Sections of the building re-opened to the public in late 2005 after a long restoration, and parts are still inaccessible.

Located in the center of Florence, this is a rare museum, very interesting to get a sense of what life was like during the Renaissance.

The narrow building extends to a height of five floors, but the top floor was only added in the 16th century. The three portals on the ground floor would originally have been open onto the street for the purposes of trade, as was common practise in the 14th century.

In the ceiling of the ground floor loggia there is a reminder of the defensive function of the palace in the form of four openings through which molten lead could be poured onto any attackers below!

The wrought ironwork on the outside of the palace is the earliest in the city to survive intact. The horizontal bars, which run across the facade on the upper floors, would have been used for displaying costly silk banners decorated with the family coat of arms. Cages containing exotic birds and small animals would have been hung from the hooks.

The palace is now home to one of the most fascinating museums in Florence, the Museo della Casa Fiorentina Antica, which attempts to recreate the atmosphere of everyday life in a medieval house. The original furnishings were sold at the turn of the century (the furnishings one now sees come from other museums and collections), but one can still see a number of the original wall paintings, which date from as early as the 14th century.

On the second floor there is La Sala dei Papagalli (The Hall of the Parrots), which has geometric patterns on the lower part of the walls topped by a frieze of trees filled with parrots. In La Sala dei Pavoni (The Hall of Peacocks), the walls are painted with geometric patterns and heraldic crests to create the impression of wallpaper. On the third floor, only the bedroom is frescoed, with scenes from a medieval legend, the Chatelaine de Vergi.

Florence | Palazzo Davanzati

Via porta Rossa

Open weekdays, 8.15 – 13.30

Early History

|

| The palazzo was commissioned in the mid 14th century by the Davizi family, who were members of the Arte della Calimala (wool guild). The Davizi had to sell in 1516 due to financial difficulty, and the building changed hands twice before being owned by the Davanzati family (that give the building its name), who had it until 1838; at which point it was converted into apartments and fell into a state of disrepair.

Purchased in 1904 by the antique dealer Elia Volpi, It was restored and opened in 1910 as a museum. The collection of this museum was always in flux, since Volpi also used it partially as an antique showroom and the objects were for sale! In his restoration, the frescoes were enthusiastically in-filled, and the furnishings reflected the scholarship of the day on how the early Renaissance palazzo must have looked. This initiative must be taken into consideration in light of the late 19th century revival of the Florentine Trecento, fathered by Americans like Bernard Berenson (the art historian) and Herbert Horne (the collector; his place is also a museum).

A complicated history characterizes the war periods, with lots of changing of hands. In the 50’s the palazzo reopened as a state museum, but the money for restoration was not enough to keep it standing. It was closed in 1995 because the building was falling down. It is now being opened again after 10 years of restoration.

The restoration has been major. The whole building had to be secured; floors were taken up and relaid, walls consolidated and frescoes repainted. The architectural framework is now safe and the work that is left to be done is on the walls and then the refurnishing of the museum. It’s an interesting place to visit already, and will be even more so when completed. Hopefully the scholars on board will take into account the vast scholarship now available on domestic architecture and furnishings, which has blossomed in the past 40 years, when choosing how to set up the new museum. New literature on the Palazzo Davanzati would also be a big step, since there are only a few books on it and they are not highly informative.

EXTERIOR

The facade was added to a grouping of medieval tower houses that were purchased with the intent of unifying them. The topmost level is an open loggia that was added in the 16th century.

INTERIOR: Ground Floor

The palazzo is in some ways typical of trecento family architecture in that it is rather well reinforced. The ground floor, now accessed by large doors set in arches, was before an open space (loggia) for commercial use. These kinds of spaces were typical of Florentine palaces of the 14th century, and can be related to the city’s strong merchant population. The loggia was used for storage or business, while the family lived upstairs, in this case with two levels of living quarters and the top level dedicated to cooking and servants.

The entrance loggia is now used as an exhibition space. Usually on display is the prized birth tray by Lo Scheggia, the younger brother of Masaccio [2010: this is now exhibited in the upstairs bedroom]. A birth tray is an object commissioned either to celebrate or to encourage a birth in the family. The front of Lo Scheggia’s tray shows the “gioco della civetta“, a game that youths played apparently in a piazza. Although this game continued into the 19th century i have been unable to figure out exactly what was involved, other than that three participants are required, and that the one in the middle has to place his feet on top of those of his companions… !! The back of the tray shows two little boys, or “putti”, also playing. They are trying to grab each others’ private parts.

Through the loggia you reach an open courtyard and a stone stairway reaching to the first floor. Notice that, beyond the first floor, the upper part of the stairway is built in wood, not stone. This might be done so that, in case of riot, the family could hole up upstairs and knock down the stairway so that nobody could get at them. This remains part of tower-home mentality. On the other hand, the concept of a courtyard as a communicative space for the whole building is rather new. It indicates a certain amount of spatial planning. Also, the courtyard was a private space for the family. The use of a courtyard as both a practical and a familial space was theorized in the 15th century, and the courtyard became a standart part of palace architecture.

UPSTAIRS

On the first floor above ground, the “piano nobile” in Italian, the front room was for business affairs. In correspondence with the three openings of the loggia below are three holes in the ground that can be revealed by opening up trap doors. These permitted the owner to check who was coming in, and in case of undesireables, drop heavy things on their heads. A storage nook in the wall behind one of these holes now contains a stone ball and I imagine this space was used to store defense objects like that. The room has a few pieces of furniture and paintings from the 15th and 16th centuries now on display, suggestive of what it might have looked like before. On the central wall of this room, adjacent to the courtyard, take note of the well, which permitted residents to draw water throughout the whole house.

The Sala dei Pappagalli (room of the parrots). A room adjacent to this one is set up like a dining room, and has a large fireplace. The much-restored frescoes on the wall (at this point more rightly called wall paintings than true frescoes) have a pattern of diamonds and parrots after which the room is named.

A very small room in between this one and the next was a bathroom, with a potty hole. Florentines reinvented indoor personal hygeine, which was known to the Ancients but lost in the middle ages.

Next to this bathroom was the study, or studiolo. Its wall paintings are now lost, but it is suggestively set up with objects that one might find in the man of the house’s room used for storage of business and recreational items. On display are a forziere (safe or strongbox), a cassone covered with velvet (more rightly found in a bedroom), some chairs, some small bronze statuettes, and some paintings with mythological scenes.

Accessed from the hallways is a bedroom set up with an antique bed and crib, as well as with other objects that would be found in the Renaissance home, like devotional paintings and a cassone. There is an “ensuite bathroom” with wash basin and other apparatus (though no hole connected to the central drainage system here).

Sections of the upper floors of the buliding are still under restoration, but each has the same layout as the first floor, and was used for family living.

The third floor hosted the kitchens, since this was most convenient for dispelling the heat of cooking, as well as in case of fire. There is an interesting display of practical objects from everyday life, like spinning tools and cooking pots. Servants’ quarters were also up here. As of Summer 2009, the kitchens are open for guided visits (free with entry) every hour on the hour. You must phone to reserve a slot, or be available to wait until there is a free space on the tour.

CONCLUSIONS

The walls of all these rooms were once decorated with frescoes; where they do not represent realistic scenes they were patterned in imitation of the tapestries that would have hung on special occasions or in winter to keep warm. Those that are now on view are heavily restored (ie, in-painted). They must be taken only as illustrative of the “early renaissance palazzo” but not considered for stylistic elements.

The art-historic significance of this palazzo is mainly its architecture, as an example of a typical domestic building of the mid trecento. However, the various changes in the quattrocento and the major restorations of the 19th and early 20th century make it hard to use as a “document”. However, many forward thinking elements, like the courtyard that gives access to all the rooms, and the desire to create a logical space for family life, are important predecessors of the great 15th century palaces, like those built by the Strozzi and Medici.

|

|

Palazzo Davanzati Palazzo Davanzati

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Mediateca di Palazzo Medici Riccardi | Giovanni di ser Giovanni, known as lo Scheggia (San Giovanni Valdarno (Arezzo), 1406- Florence, 1486)

Art in Tuscany | Lo Scheggia

Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance Cassoni paintings

Pope-Hennessy, John, and Keith Christiansen. "Secular Painting in 15th-Century Tuscany: Birth Trays, Cassone Panels, and Portraits." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 38, no. 1 (Summer, 1980)

Palazzo Davanzati | www.museumsinflorence.com

Damien Wigny, Au coeur de Florence : Itinéraires, monuments, lectures, 1990

Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, Art, Marriage, and Family in the Florentine Renaissance Palace (YUP 2009).

Marta Ajmar; Flora Denni; At Home in Renaissance Italy, Victoria and Albert Museum (November 1, 2006), London. Catalogue of an exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in 2006 | Victoria and Albert Museum, Online Museum

At Home in Renaissance Italy reveals for the first time the Renaissance interior’s central role in the flourishing of Italian art and culture. The exhibition provides an innovative three-dimensional view of the Italian Renaissance home, presented as object-filled spaces that bring the period to life. The exhibition showcases masterpieces by Donatello, Carpaccio, Botticelli, Titian and Veronese, and exquisite treasures from the Medici and other private collections,

[1]

In the 1390s, when Francesco Datini built his palace at Prato, the principal room (characteristically, it was an office for the transaction of business, not a place of entertainment) was again decorated with landscape frescoes, but the ratio between ornament and representation underwent a change. Decoration (geometrical decoration on this occasion, not a fictive textile) is confined to the base of the walls, and the area of landscape is deepened so that an entire wood is portrayed, with trees receding into the far distance, filled with birds and animals. Datini had lived at Avignon, where he must have seen French fourteenth-century secular frescoes, and the decoration of his office may have been French in inspiration, like the later, much more complex frescoes planned by Leonardo da Vinci for the Sala delle Asse of the Castello Sforzesco in Milan. A notoriously successful entrepreneur-he dealt in cloth and many other commodities- Datini was able, when transacting business in his office, to pursue imaginary journeys through the forest on his walls. The society to which he and most of the prosperous patrons of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries belonged was pragmatic and commercial. Whether they were bankers or merchants, its members were concerned with making money, and with bettering the worldly position of their families. The symbol of their aspiration was the palace, which served, as Leon Battista Alberti tells us, as the physical embodiment of the historic unit of the family This point must be borne constantly in mind in examining its decorations and its furnishings. The frescoes in the Palazzo Datini and the Palazzo Davanzati have in common an obsessive insistence upon heraldry On the ceiling of the office in the Palazzo Datini there appear, twice repeated, the arms of Francesco Datini and of his wife, who had been born Bandini, and the fictive textile design in the Palazzo Davanzati similarly has a border decorated with little coats of arms. In this ambitious, rather austere society marriage and childbirth were of the utmost consequence. Marriage could be celebrated by ostentatious expenditure, like that involved in the carving of a chimneypiece by Desiderio da Settignano when Giovanni Boni married Camilla Marsuppini in 1463, or less extravagantly by the purchase of a chest or chests with the heraldic bearings of the bridal pair. Not all cassoni were made for marriages (though the word is now generally translated "marriage chest"), and some of them must have been commissioned for no better reason than that a chest or a container was required. For Giorgio Vasari, writing in the middle of the sixteenth century, the custom seemed an odd, old-fashioned one. 'At that time," he tells us in his life of the painter Dello Delli, "large wooden chests like tombs were in use in people's chambers with the lids variously decorated. Everyone had these chests painted. The front and ends were decorated with various narrative subjects, and the corners and other parts were enriched with the arms or insignia of the house." Not only chests, Vasari goes on, but beds and cupboards and moldings were decorated in this way In his time a number of such works by artists "non mica plebei" ("of no mean talent") were preserved in the Palazzo Medici, and there were indeed other Florentine palaces in which the owners had likewise preserved them, and had refrained from replacing them with "ornamenti e usanze moderne." Childbirth was celebrated by the commissioning of painted trays, generally with a narrative scene on the front and the coats of arms of the parents on the back. Initially, they appear to have been used for the ritual presentation of sweetmeats and other offerings to the mother during the period of lying-in, but they were then preserved (like modern christening cups) by the child for whom they had been made. When Lorenzo il Magnifico died in 1492, one of the objects recorded in his apartments in the Palazzo Medici was his desco da parto or birth tray. In the fifteenth century in Florence the urge toward commemoration was extremely strong; inevitably, it affected not only marriage and childbirth but death too. It was morally incumbent on the heads of families to maintain a family tree, and when portraits were made of members of the family, the impulse likewise was commemorative. To our eyes the profile portraits produced in the middle of the fifteenth century look very little lifelike; but they were not conceived as modern snapshots. Some of them are systematic reconstructions of their subjects' features, painted posthumously and some of them are life portraits made for the information of later generations, who would otherwise recall the sitter as a mere name in the ricordi of the family.

Pope-Hennessy, John, and Keith Christiansen. Secular Painting in 15th-Century Tuscany: Birth Trays, Cassone Panels, and Portraits. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 38, no. 1 (Summer, 1980), p.3.

[2] Giovanni di Ser Giovanni Guidi, known as lo Scheggia Lo Scheggia (San Giovanni Valdarno, nr. Arezzo 1406-1486 Florence) was the younger brother of Masaccio? During a long career, he built up a successful workshop, a major speciality of which was the production of narrative panels for cassoni (marriage chests). Cassoni had an important place in Florentine domestic interiors in the quattrocento. A number of workshops specialised in their production, the most familiar being that of Apollonio di Giovanni and his associate Marco del Buono. The main panel of the Cook cassone is of the same subject as one of the finest extant examples, The Triumph of David, once in the Medici collection and more recently at Lockinge, now in the National Gallery, London, by Francesco Pesellino. That panel is the right hand element of a pair, answering one of the Slaying of Goliath. As a hero of the Old Testament, David was held in especial veneration in Renaissance Florence, as statues by every major sculptor from Donatello to Michelangelo so spectacularly attest. Five cassone fronts of the Triumph of David were known to the late Ellen Callmann. She suggested (p. 39, no. 4) that the Cook work was the pair to a panel of the Slaying of Goliath, formerly in the Spiridion Collection, Paris (P. Schubring, no. 115). Callmann further argued (pp. 44-5) that the testate were originally associated with the panel, and noted that the subjects of these offered classical parallels to the 'Old Testament example of Virtù' of the main panel.

Of Florentine cassone of after 1435, Ellen Callmann ('William Blundell Spence and the transformation of renaissance cassoni', The Burlington Magazine, CXLI, December 1999, p. 342) considered that 'fewer than six original examples' survive. Numerous panels were, however, set in new chests by Florentine craftsmen to satisfy a demand for the most part from English collectors, from whom Spence catered. In view of Sir Francis Cook's interest in sculpture and the applied arts, as well as pictures, it is not surprising that he obtained a number of cassone panels as well as this chest.

|

The hidden secrets of southern Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

Podere Santa Pia is a beautifully renovated holiday house, located 350 meters above sea level

in a panoramic position, overlooking the vineyards and beautiful hills of the Maremma.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden |

|

Villa di Catignano |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cortona, Santa Maria de Nuova |

|

Orvieto, Duomo |

|

Florence, San Miniato al Monte

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Palazzi a Firenze / Palaces in Florence | Palazzo Acciaiuoli, Palazzo Adorni Braccesi, Palazzo degli Alessandri, Palazzo dell'Antella, Palazzo Antinori, Palazzo Arcivescovile, Palazzo dell'arte dei Beccai, Palazzo dell'Arte dei Giudici e Notai, Il Bargello, Palazzo Bartolini Salimbeni, Palazzo de' Benci, Palazzo di Bianca Cappello, Palazzo Buondelmonti, Palazzo dei Canonici, Palazzo Capponi Covoni, Palazzo Cocchi-Serristori, Palazzo dei Congressi, Palazzo Corsini, Palazzo Corsini al Prato, Villa Corsini a Castello, Palazzo Da Cintoia, Palazzo della Gherardesca, Palazzo Fenzi, Palazzo dei Frescobaldi, Palazzo Galileo, Palazzo Gondi, Palazzo Lenzi (French Consulate), Palazzo Giugni, Palazzo Guadagni, Palazzina della Livia, Palazzo Malenchini-Alberti, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Palazzo Mellini Fossi, Palazzo della Misericordia, Palazzo della Missione, Palazzo dei Mozzi, Palazzo Nasi, Palazzo Nonfinito, Palazzo Pandolfini, Palazzo Pazzi, Villa la Petraia, Palazzo Pitti, Palazzo Portinari Salviati, Palazzo delle Poste Centrali, Palazzo Pucci, Palazzo Ramirez de Montalvo, Palazzo Ricasoli, Palazzo Rucellai, Palazzo Sacrati (Guadagni-Strozzi di Mantova), Casino Salviati, Palazzo di San Clemente, Palazzetto Serragli, Palazzo Serristori, Palazzo Spini Feroni, Palazzo Strozzi, Palazzo Taddei, Palazzo Torrigiani Del Nero, Palazzo Uguccioni, Palazzo di Valfonda, Palazzo Vecchio, Villa il Ventaglio, Palazzo dei Visacci, Palazzo Vivarelli Colonna |

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()