| |

|

|

|

|

|

The church also contains the alleged portrait of Amerigo Vespucci, the man who gave his name to the Americas.[2] In the second bay of the nave, just below Botticelli’s painting, there is a fresco of The Madonna della Misericordia by Ghirlandaio.

The young boy, whose head appears under the Virgin's right arm, between her and the man in the red cloak, is supposed to be a portrait of the explorer, Amerigo Vespucci. A plaque marking his tombstone can be seen in the floor to the left of the altar.

Amerigo Vespucci was an Italian explorer, financier, navigator and cartographer who first demonstrated that Brazil and the West Indies did not represent Asia's eastern outskirts as initially conjectured from Columbus' voyages, but instead constituted an entirely separate landmass hitherto unknown to Old Worlders. Colloquially referred to as the New World, this second super continent came to be termed "America", deriving its name from Americus, the Latin version of Vespucci's first name.

|

|

Portrait of Amerigo Vespucci as a child, part of the Madonna della Misericordia by Domenico Ghirlandaio at the Ognissanti church in Florence[1]

|

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, about 1472, fresco, Ognissanti, Florence

|

“La Madonna della Misericordia e della Pietà” (1472 ca.) is a teamwork by the brothers Domenico and Davide Ghirlandaio. The fresco is located above the altar of the Vespucci Chapel. It presents several members of the Vespucci family, who had a special devotion to this Church, having always been one of its main benefactors. An adolescent Amerigo Vespucci can be identified under the protection of the Madonna.

The next Chapel hosts La Madonna in Trono (1565) by Santi di Tito.

The following Chapel houses Il Martirio di S. Andrea by Matteo Rosselli (1578-1650).

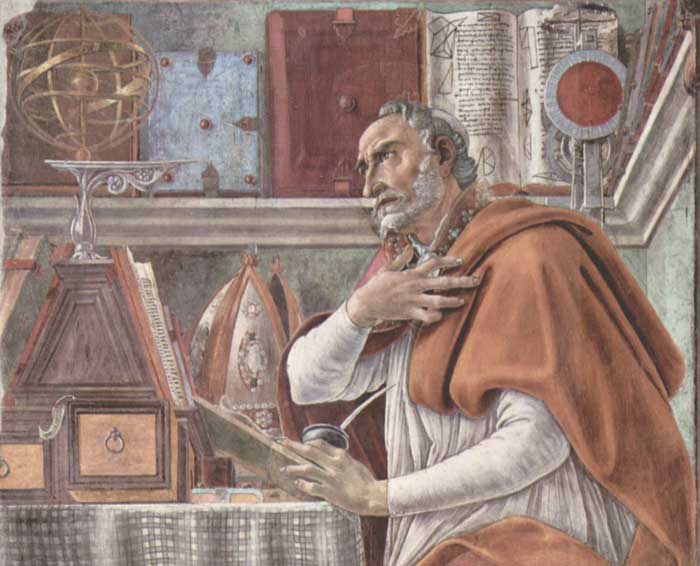

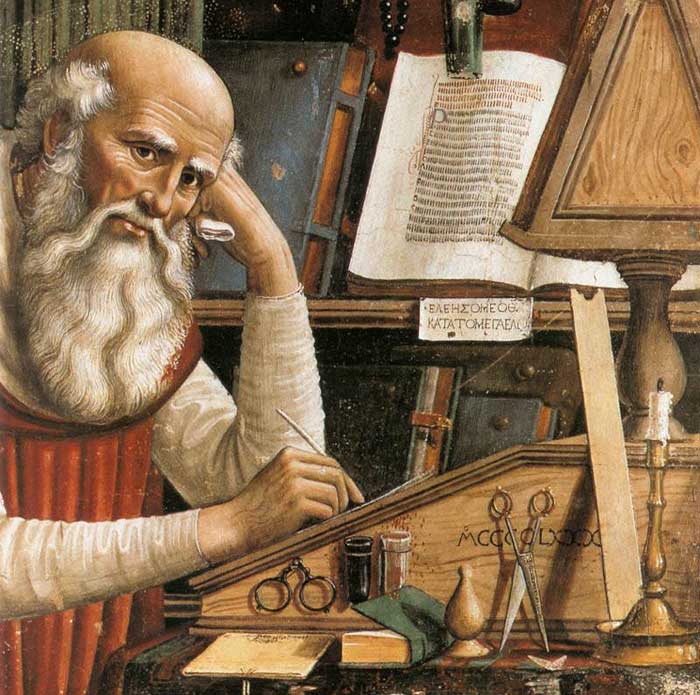

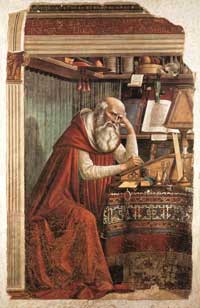

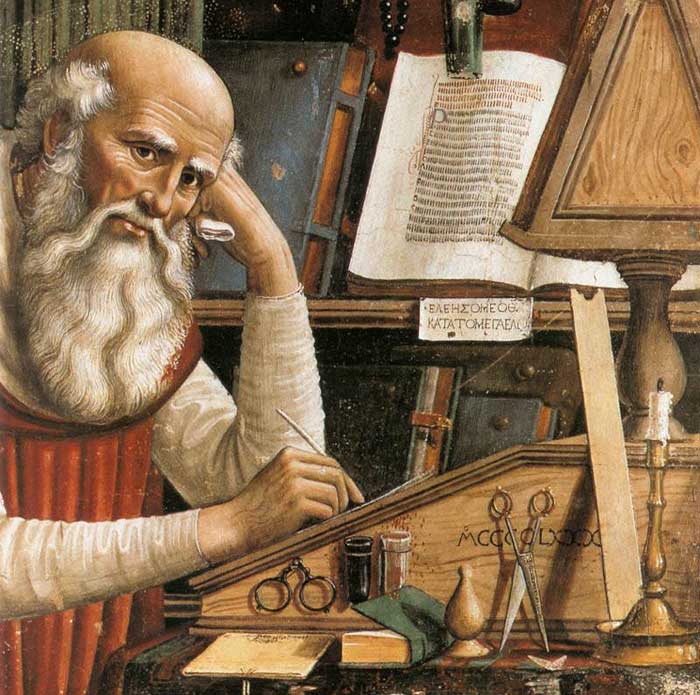

Above the confessionals there are two wonderful frescoes: “S. Girolamo” by Domenico Ghirlandaio and “S. Agostino nel suo Studio” by Sandro Botticelli.

The first chapel to the left preserves the habit worn by S. Francesco d’Assisi when he received the Holy Stigmata, the 29th September 1224, while he was fasting on devotion to the Archangel S. Michael on the Mount della Verna, situated in the Tuscan territory of Casentino.

In the Sacristy there are many artworks from the Early Renaissance. The most relevant are:

A Crucifixion by the Tuscan architect and painter Taddeo Gaddi (1300ca.-1366) and another one attributed to a follower of Giotto, as well as La Resurrezione e l’Ascensione by Agnolo Gaddi (1350 ca.- 1396), son of Taddeo Gaddi.

The Refectory is situated between the two cloisters of the former Convent. The huge room has a superb entry door in malleable stone with a washbasin included in each side, dated 1479 ca.

The large vaulted niches are ornamented with frescoes by Giuseppe Romei (1770 ca.) depicting some biblical episodes related to water’s intensity.

Covering an entire wall of the Refectory there is an imposing masterpiece by Domenico Ghirlandaio: L’Ultima Cena (The Last Supper).

|

|

Lamentation over the Dead Christ, c. 1472, fresco, Ognissanti, Florence

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Madonna of Mercy, c. 1472, fresco, Ognissanti, Florence

|

The tombstone of Sandro Botticelli can be found in the floor of the Cappella San Pietro d’ Alcantara in the south transept. There is Botticelli's fresco of Saint Augustine in his Study (1480) in the same church.

|

Sandro Botticelli, St. Augustine in His Studio

|

In 1480, Botticelli was commissioned to paint the fresco St. Augustine (1480) for the Ognissanti church. [1] At that period he also created another fresco, which did not survived.

Botticelli learned the basic techniques associated with fresco painting while working for his teacher, Filippo Lippi. We know of documents, telling of paintings that have since been destroyed, that Botticelli was greatly in demand as a master of fresco paintings during the last three decades of the Quattrocento. He painted for the Vespucci family the St Augustine in the church of Ognissanti. It was created in competition with Ghirlandaio's fresco of St Jerome.

|

|

Sandro Botticelli, St. Augustine in His Studio, 1480, fresco, Church of Ognissanti, Florence

|

| The fresco of St Augustine (1480) by Botticelli can be found half way along the nave on the right hand side. On the opposite side of the nave is a fresco (detached) of St Jerome (1480) by Ghirlandaio.

St Augustine (left) is one of the four Fathers of the Catholic church and Botticelli has portrayed him studying alone in his room. If you look closely at the painting, you will see a clock in the top left hand corner. The single hand of the clock is pointing between ‘I’ and ‘XXIIII’, the moment before sunset. The fact that the saint is shown in his cell at a specific time of the day relates to a vision that he is alleged to have had.

The story goes that St Augustine was meditating in his study on the fortune of the saints and was about to write to St Jerome to inform the latter of his reflections, when suddenly St Jerome appeared to him in a vision. St Jerome explained to him that it was impossible to describe the feeling of rapture, if one had not experienced it oneself, as he had at that very moment - the hour of his own death. It is this vision that Botticelli has tried to suggest in the fresco and it also explains the pairing of the two saints on opposite sides of the church. Both frescoes are filled with finely-observed details.

St Augustine has been interrupted at his studies. He is deeply moved as he raises his eyes, and, in an expansive gesture, lays his right hand to his chest: for he is seeing a vision of the death of St Jerome.

The entablature at the top is an architectural feature which Botticelli continued into the depth of the picture, in order to place a row of large books and astronomical instruments on it. Botticelli shows the room and the saint from a low angle which enables the artist to give greater emphasis to Augustine's dramatic gesture.

St. Augustine in His Studio ortrays Augustine of Hippo in meditation within his studio. The Coat of Arms visible in the upper part is that of the Vespucci family; it has been supposed that the picture was commissioned by Amerigo Vespucci's father.

The lines in the book over the saint's head are mostly meaningless, apart from a line in which reads: Dov'è Frate Martino? È scappato. E dov'è andato? È fuor dalla Porta al Prato ("Where is Fra' Martino? He fled. And where did he go? He is outside Porta al Prato"), probably referring to the escapades of one of the monks of the church's convent.

|

|

Sandro Botticelli, St. Augustine in His Studio, 1480, fresco, Church of Ognissanti, Florence

|

| A small round stone in the Franciscan Church of Ognissanti marks the resting-place of Sandro Boticelli (Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi), who is buried near his beloved Simonetta Vespucci. In the centre of the tombstone one can see the Filipepi family coat of arms, surrounded by the inscription in Latin containing the year of the artist's death - 1510. |

|

|

In 1480, Ghirlandaio painted the Saint Jerome in His Study and other frescoes in the Church of Ognissanti, and a life-sized Last Supper in its refectory.

|

Saint Jerome in His Study

|

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Saint Jerome, (detail), Inscribed with the date on St. Jerome's desk: MCCCCLXXX,

1480, fresco, 184 x 119 cm, Florence, Ognissanti

|

n 1480 Ghirlandaio frescoed in the church of Ognissanti (All Saints) a St Jerome that rivalled the St Augustine which Botticelli had painted there a short time before. This work, which was accomplished with excessive ease, is superficial and full of objects that suffocate and impoverish its impact. The direct comparison with the Botticelli Saint serves merely to underline an unsatisfactory period for Ghirlandaio.

In contrast with the St Jerome Ghirlandaio painted in Cercina, this St Jerome is not depicted as a penitent but as the scholarly translator of the Bible.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Domenice Ghirlandaio, Last Supper frescoe

|

The Refectory is situated between the two cloisters of the former Convent. The huge room has a superb entry door in malleable stone with a washbasin included in each side, dated 1479 ca.

The large vaulted niches are ornamented with frescoes by Giuseppe Romei (1770 ca.) depicting some biblical episodes related to water’s intensity. Covering an entire wall of the Refectory there is an imposing masterpiece by Domenico Ghirlandaio: L’Ultima Cena (The Last Supper).

|

|

Domenice Ghirlandaio, Last Supper,1480, fresco, 400 x 880 cm, Chiesa di Ognissanti, Florence

|

When you leave the church turn right and you will soon see a door, which leads through a cloister to the old refectory of the Ognissanti. The end wall of the refectory is decorated with a delightful fresco of The Last Supper (1480) by Domenico Ghirlandaio.

This version of the Last Supper, executed in the refectory of the convent of the Ognissanti [3] was executed in the same year as the St Jerome in the church. It is a famous example of the Tuscan tradition of depicting the Last Supper in monastic refectories.

Jesus and the Apostles are sitting at a lengthy table placed opposite to the back wall of the room. In the centre of the wall there is a large pointed open window from which is visible an allegorical grove to the Olive Mount.

Jesus is sitting in the centre. To his left is S. John and to his right S. Peter. Judas Iscariot is separated from the other Apostles, being seated in front of the table.

Domenico Ghirlandaio painted this scene several times along his life. At the present, only three of them still exist and they are all preserved in Tuscany. The first one, which is a teamwork with his brother Davide, is dated 1476 and is hosted in the Refectory of the Badia dei Santi Michele e Biagio situated in Passignano sul Trasimeno. The second one (1480) is conserved in the Refectory which we are referring to and is somewhat bigger than the other two. The third one (1486) is housed in the Florentine Church of San Marco.

Art in Tuscany | Domenice Ghirlandaio, Last Supper frescoes |

|

|

|

Giotto's Crucifix

|

Formerly in the sacristy for 84 years, Giotto's monumental Crucifix is back in the Florentine church for which it was painted in 1310-1315, after a careful 8-year long restoration by the Opificio delle pietre dure (OPD) which has restored the luminosity and brilliance of its colours and glazes, its volumes and its modelling.

|

|

|

Giotto was renowned in his day for creating religious images that communicated directly with congregations. In contrast with stylised Byzantine art, his depiction of key scenes from the New Testament was thought daring and his newly rediscovered cross shows the crucifixion as a human triumph, with the image of the risen Christ painted above the dying figure on the cross.

The Ognissanti Crucifix was a neglected Italian treasure which a team of experts have now repaired and identified. After long being attributed to a relative or school of the early Renaissance artist Giotto, the Ognissanti crucifix is now believed to be the work of the 14th-century Italian himself. The painted cross, which hangs in the Ognissanti church in Florence, underwent extensive cleaning by the local restoration lab Opificio delle Pietre Dure. The project was led by art historian Marco Ciatti, who has concluded that the crucifix is a Giotto masterpiece dating from the 1320s.

The majestic tempera on panel realised by Giotto and his workshop around 1310-1320 had been sadly neglected for centuries. Kept in the sacristy of the church of Ognissanti, it was rarely seen and the vigorous modelling of the flesh tones of the figures, and the many precious details of the pictorial surface, were hidden by a severely altered layer due to a treatment of the past and century-old grime. The restoration of Giotto's Ognissanti Crucifix was started by Paola Bracco in 2002.

The crucifix is situated in a chapel to the left of the transept. The crucifix was originally located above the rood screen in the transept of the Ognissanti church, but this no longer exists.

Art in Tuscany | The return of Giotto's Crucifix

Art in Tuscany | Santa Maria Novella | The Crucifix by Giotto

Address.

The Chiesa di Ognissanti is situated in Via Borgognissanti, n. 42, close to the same name square,

in the neighbourhood of the Lungarno Amerigo Vespucci.

|

|

|

| |

|

[1] St. Augustine is the subject of two paintings by the Italian Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli. The first, executed in 1480, is in the church of Ognissanti in Florence. The other is in the Uffizi, also in Florence.

[2] Amerigo Vespucci was a daring seafarer who led a number of voyages to explore South America. Vespucci worked for Lorenzo de' Medici and his son, Giovanni.

He explored the eastern coast extensively between 1499 and 1502. It was during this time that he discovered that the continent extended further than the landmass on record and discovered what we now know as the Indies. Vespucci's voyages were widely known all over Europe through his published accounts. It was not until 1507 that cartographer Martin Waldseemüller generated a revised world map that highlighted the new continent and named it America after the explorer's first name.

In the Vespucci chapel, a fresco by Domenico Ghirlandaio with his brother David (about 1472), of the Madonna della Misericordia protecting members of the Vespucci family, is reputed to include the portrait of Amerigo Vespucci as a child.

Simonetta Cattaneo de Vespucci, nicknamed la bella Simonetta (ca. 1453 – 26 April 1476) was the Genoese wife of the Italian nobleman Marco Vespucci of Florence. She also is alleged to have been the mistress of Giuliano de' Medici, Lorenzo the Magnificent's younger brother. At age fifteen or sixteen she married Marco Vespucci, son of Piero, who was a distant cousin of the famous Florentine explorer and cartographer Amerigo Vespucci.

Simonetta and Marco were married in Florence. Simonetta was instantly popular at the Florentine court. The Medici brothers, Lorenzo and Giuliano took an instant liking towards her. Lorenzo permitted the Vespucci wedding to be held at the palazzo in Via Larga, and held the wedding reception at their lavish Villa di Careggi. Through the Vespucci family Simonetta was discovered by Sandro Botticelli and other prominent painters upon arriving in Florence. Before long every nobleman in the city was besotted with her, even the brothers Lorenzo and Giuliano of the ruling Medici family. Lorenzo was occupied with affairs of state, but his younger brother was free to pursue her.

Some suggest that Botticelli also had fallen in love with her, a view supported by his request to be buried at her feet in the Church of Ognissanti - the parish church of the Vespucci - in Florence. His wish was in fact carried out when he died some 34 years later, in 1510.

[3] The return of Giotto's Crucifix by Goffredo Silvestri

|

|

Amerigo Vespucci as a child |

Art in Tuscany | St. Augustine in His Cell (Botticelli), a later version of the same theme

St. Augustine in His Cell, is a painting by the Italian Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli, finished around 1490-1494. It is housed in the Uffizi, in Florence. This work was probably executed for an Augustinian hermit of Santo Spirito, as shown by the fact the saint wears both episcopal and hermit garments. As many of Botticelli's late works, it is inspired by the religious predication of Savonarola.

The Guardian | British art restorer uncovers a lost Giotto masterpiece

Damien Wigny, Au coeur de Florence : Itinéraires, monuments, lectures, 1990

|

| This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia article St. Augustine (Botticelli) and Ognissanti, Florence published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cappella Vespucci, and Ognissanti (Florence) - Interior. |

| |

|

|

The hidden secrets of southern Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

Podere Santa Pia is situated in panoramic position in the Maremma countryside. On a clear day you can see as far as Corsica to the south.

|

| |

|

|

The return of Giotto's Crucifix

|

|

|

|

|

Formerly in the sacristy for 84 years, this monumental work is now back in the Florentine church for which it was painted in 1310-1315, after a careful 8-year long restoration by the Opificio delle pietre dure (OPD) which has restored the luminosity and brilliance of its colours and glazes, its volumes and its modelling.

Someone should have the patience to write a history of art recounting the crimes of displacement of art works in churches when convenient, to the point of their destruction either through loss or damage. For example Duccio's Maestà, which hung on the high altar of Siena Cathedral until 1506, when it was moved to a wall in the transept. In 1771 the two painted sides of the panel were split into two separate paintings, hung in two separate chapels, while another part hung in the sacristy. Soon afterwards these parts were sold to collectors and foreign museums.

In this particular history of art, one of the foremost places is occupied by the monumental Crucifix by Giotto (4.67m high by 3.60m wide) in the Florentine church of Ognissanti (All Saints). Painted according to historians either in the period 1310-1315 or in the 1320's for the monastic order of the Umiliati who then occupied the church and convent, it was located on the partition wall about four feet high that separated the choir reserved for the clergy from the nave for the faithful.

|

|

|

This wall, which also had a central doorway, would have seemed to our eyes like a brutal obstruction, but it must have been spectacular, since the Crucifix was accompanied by four other panels by Giotto mentioned by Ghiberti (who wrote a century after the death of the master): the large (325cm x 204cm) Madonna and Child enthroned among the angels (the famous Madonna of Ognissanti now in the Uffizi), the small (75cm x 178 cm) Dormition of the Virgin in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, the Madonna with the Child in her arms (now lost), and an unknown panel.

In addition, the wall was also decorated with frescoes by Domenico Ghirlandaio (St Jerome in his Study) and Botticelli, who is buried in the Church (St Augustine in his Study).Between 1564 and 1566 Vasari had the wall demolished (with the detachment and transfer in one piece of the frescoes to the refectory) and the Ognissanti restructured (like Santa Maria Novella and other churches) in line with the liturgical changes made by the Council of Trent in 1563. The Crucifix was moved to the wall at the side, then to a chapel in the transept which was used as a cloakroom, where, squeezed between two wardrobes, the Crucifix was neglected and abused to the point of physical damage. Finally, it was moved to the sacristy in 1926, when that arm of the transept was converted into a memorial of the First World War. So for the last 84 years Giotto's Crucifix has virtually disappeared, passsed into oblivion even for the faithful. But who recalls that in 2000 Antonio Paolucci, then a conservator, in an "acclaimed concession" loaned the Crucifix to the historic exhibition at the Galleria dell'Accademia, which was the resumé of the "critical appraisal of sixty years of studies and research on Giotto." The Crucifix was billed as "Giotto" in the exhibition conceived and curated by Angelo Tartuferi and Franca Falletti, and as "follower of Giotto" ('Parente di Giotto') in the accompanying volume of critical appraisal.

The loan of the Crucifix had been conditional on its subsequent restoration, and the Opificio delle pietre dure, once work on the earlier (1285-1290) Giotto Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella had finished in 2001, began painstaking work on the Ognissanti Crucifix the following year. And now, after eight years of study, scientific examination, the search for a new method of cleaning, and restoration, once again the Crucifix appears in the church of Ognissanti, in the raised chapel in the left transept, the Cappella dei Caduti (chapel of the fallen), accessed by a small flight of steps. Mounted on a newly designed metal base, it now stands, looking almost relieved to be back, under the ancient Gothic arches, even more so thanks to the lighting system from below and its slight forward inclination (as it used to be on the partition wall). In the Santa Maria Novella, the Giotto Crucifix had been relocated back to its old "more respectable" position in the centre of the nave. Something impossible in the Ognissanti while "preserving all the restructuring work of the sixteenth century and the Baroque period," and in the nave there is no space.

|

|

Ognissanti Madonna, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

The church of Ognissanti was founded in 1251 by the Umiliati friars, followers of St. Benedict, who, while keeping faith with their Lombard origins, had adopted a fruitful life of production and trade in wool cloth in Florence, whose earnings were used for works of charity. Unfortunately, when the Umiliati were replaced in 1561 by the Minor Observant Franciscans, their archives were destroyed or dispersed. But the great works of art remained: in the Chapel of the Vespucci family, two frescoes by Ghirlandaio, the principal illustratore of the age of Lorenzo the Magnificent: the Madonna of Mercy and the Pietà, in the sacristy the Crucifixion fresco by Taddeo Gaddi, and in the refectory the fresco of the Last Supper by Ghirlandaio and, as mentioned above, the frescoes by Ghirlandaio and Botticelli from the partition wall.

There were three directors of the OPD during the period of restoration (Cristina Acidini, Bruno Santi and Isabella Lapi Ballerini), while the work itself was overseen throughout by Marco Ciatti (head of the restoration laboratory for paintings on panel and canvas) and Cecilia Frosinini (head of the fresco division, which had already begun a diagnostic examination, "with significant results," of another work, "completely" Giotto's, the cycle in the Peruzzi chapel). Ciatti also edited the book L'officina di Giotto (Giotto's Workshop, 252p, published by Edifir, in the valuable series Problemi di conservazione e restauro) which includes both technical details of the restoration and critical perspectives...

In the Crucifix (painted in egg tempera), Christ is represented as Christus patiens, suffering, about to expire. The tension in the muscles of the arms is treated with delicacy, but the ashen colour is so imprinted in the flesh that it is a "true body", of a sculptural consistency that suggests it was modelled from life. The tips of the fingers are of "purest white", and the lips flushed. The body hangs on a more intimate Cross, the 'heart' of the triumphant Cross painted with gilded bands; at its centre an overflowing mosaic of starred crosses, squares and ellipses. The 'beams' of the Cross are painted in "bright, but deep and intense blue," the precious lapis lazuli inlaid with greater or lesser amounts of lead white, as in the sloping pedestal to which Christ's feet are pinned (by a single nail). The blue is crossed by thin red lines, cinnabar blood with more purplish glazes. On the forehead are a few drops of "pure red lacquer."

The Cross terminates in quatrefoils with gold backgrounds. To the left is Mary, prematurely aged, a pained expression in her characteristic slanted eyes, all wrapped up in a blue mantle that serves as a protection and almost as a hiding-place, again painted with lapis lazuli whose blue becomes more luminous when depicting the volume of her hands and covered arms. On the right is St John the Evangelist, in a pink mantle over a blue robe also painted with lapis lazuli and lead white. From his eyes a stream of tears descend, and from his mantle emerge his "most beautiful tightly joined hands", clasped so as not to explode in a gesture of despair. The preparatory drawing "shows through the thin layer of colour." The cheeks of the Virgin and of St John, the 'Mourners', show a flush caused by tears, achieved by multiple applications of cinnabar. Above is the Blessing Christ in pink robe and blue mantle, on which is mounted a large book with a red cover. Probably during the damaging period in the transept chapel of Ognissanti, the Crucifix has lost the edges of the golden quatrefoils of the 'Mourners' (remade for the exhibition of 1937 and retained in the modern restoration). Most importantly, it has lost the lower part of the Cross, just below Christ's pierced and bleeding feet, where it is probable that Giotto repeated his invention in the Crucifix of Santa Maria Novella, the rock of Golgotha with the skull of the first man to represent humanity.

Before the current restoration, the colours of the Crucifix were "extremely dim and dark" due to a layer of "very dull and greyish" surface material, negating the volumes and the modelling, the "refined decoration and detail". The test results showed an "unusual" overlay consisting of a vegetable-based gum (like apricot) and calcium oxalate, from a previous cleaning intended to "varnish" the work. Its main detrimental effect was due to its having collected dirt, fine particles of air pollution, and the soot from candles. Conversely, it maintained a layer of "very thin and old paint" on the surface. With the restoration has come a transformation from an object seen through a dirty curtain to a brightness and brilliance of the golds, the blues and the "textures"; the rivulets of blood, the details of the Christ, the contours of his chest and groin, the tense bands of muscles in his arms and legs, the strands of his hair and beard, his eyelashes. Also the glazes: not a complete innovation (neither for Giotto nor for other artists like Perugino or Pinturicchio), but nonetheless it is of great interest that Giotto in the Ognissanti work used them more extensively compared to that in the Santa Maria Novella; glazing in Christ's halo (which is painted in relief); glazed paste and painted glazes (even in minute plant motifs), and gold in imitation of precious stones and enamels, in cabochon style or pyramid shapes; in blue, green, white and reddish-white colours; in the frame red and blue glazing alternating with pale green; at the centre of the three beams a large glass-coloured painted and gilded glaze (only one survives). The scientific examination revealed residues of lead foil around the glazes, "perfectly reflective", resembling those in the halo of Christ the Judge in the panel in the Scrovegni chapel.

From the technical point of view the biggest "hitch" was to develop an "innovative" method of cleaning everything (not the traditional solvents which previous "heavy abrasions" indicated would have been disastrous), but "water-based systems" a much slower technique and used with a new type of laser. The Crucifix is in fact an "extremely delicate" painting, built up "with very thin layers of colour" and a preparatory base "extremely sensitive" to moisture, perhaps "because of a small amount of glue used as an adhesive binding for the chalk." The examination uncovered some interesting details: Giotto changed the size and position of the halo (which was lowered and reduced in size) affecting the "entire figure" of the Christ. The head would have been "much higher" than in any other of Giotto's Crucifixes. The strips of parchment and (probably used) linen, spread out over the panel as "shock absorbers" to "restrict" the natural movements of the wood under the preparatory layers and the painting itself. One of the "indicators of the care and refinement of execution" of the Crucifix is the different techniques used in painting the Blessing Christ relative to the other figures. Here the depiction of the flesh is "more compact and denser." Ciatti indicates that this is typical of Giotto (as found in the Santa Maria Novella Crucifix), the "juxtaposition of areas of meticulous and subtle brushwork and other features strongly marked by large brushstrokes, almost brusque like in some of the folds of the Virgin's mantle."

When it comes to Giotto (or other great masters) there is always a lurking doubt as to the attribution of a work, in whole or in part. Always remember - recommends Ciatti - that in the Middle Ages a work created according to the modern mind, the creation of "an individual artist, the unique and unrepeatable product of his hand and creative genius, is unimaginable." Mediaeval artistic production is "collective in nature", constructed with numerous, often specialised, collaborators, especially in the studio of a highly successful artist like Giotto, working on many commissions from major clients in different cities. The term 'studio' should not be "synonymous with inauthenticity." On the one hand "the great innovative drive and the continuing transformation of modes of expression, due to which Giotto is never repetitive nor equal to himself from one work to another, can only be traced to his own ingenuity and creativity"; on the other hand "the direct participation of a large group of collaborators" was inevitable. In the book, Arturo Carlo Quintavalle notes that in the Ognissanti Crucifix it is not simply the lobed panels at the extremities which are innovative, but "rather the emphasis on the pathos of the story", the "emotional tension" of the 'Mourners'. And the body of Christ is portrayed in "a much more analytical fashion" than the Christ of Santa Maria Novella. All these aspects can only be down to the inventiveness of Giotto. After the restoration "the primary result" is the hand of Giotto "inevitably in collaboration with his studio."

For Cristina Acidini, currently director of the Florentine art historical heritage and its complex of museums, the Crucifix (of an "unquestionable beauty of painted material"), carries after its restoration the onerous weight of a Giotto attribution in its arms, and carries it with dignity." Giorgio Bonsanti sees in the Crucifix a "slight decrease in technical quality" compared to the Crucifixes of Santa Maria Novella, Rimini and Padua... For Bonsanti the expressions of Mary and St John are a "kind of grimace." "Definitely a very intense and impressive effect," but not the universal representation of suffering charactistic of other figures painted by Giotto. The Ognissanti Crucifix is a "product, however great, of the studio of Giotto," due to the "tendency" defined as 'Follower of Giotto', as invented by Giovanni Previtali. This would have been a personality with "recognisably similar stylistic characteristics" to those of Giotto. For Ciatti the Blessing Christ must "really be the result of the hand of an assistant who either completed or began the work" in the absence of the master, with a technique similar to that used previously by Giotto, "who in the meantime had already changed." But Ciatti confirms the doubts about this 'follower' that would have accompanied the master, "almost from the beginning, for decades." A solution that does not satisfy the vast majority of critics.

Beyond the artistic evaluation, Ciatti cites the care with which Giotto, nothing short of an "astute businessman", supervised the economic aspect of his business, and says that he would never have favoured an "internal competition". It was against Giotto's interests to give the opportunity of exposure to someone of value to him, allowing him to nurture a reputation he might have profited from outside of his studio. The at least twenty-year-long relations that Giotto maintained with the Umiliati was not only an artistic one. A document dated September 1312, quoted by Alessandro Cecchi, reveals that the master was trading in "woolen" goods and charging "an exorbitant price (unum telarium francigenum)." Further documents attest to his relations with Vespignano Vicchio, since he visited the Mugello to buy land and houses. And the coins found beside the body of the painter in his grave under the floor of the old Duomo in Florence (a few yards from the tomb of Brunelleschi), serve to confirm the age of Giotto (about seventy) in January 1337, but also indicate his love of money to "to the point of usury." His teeth were his "tax return," worn down as could have been only those of someone who regularly ate "lots of meat, cooked meat above all," which "only those who had money" could afford.

(Source: Article in La Repubblica, 14th January 2011)

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()