| |

|

|

|

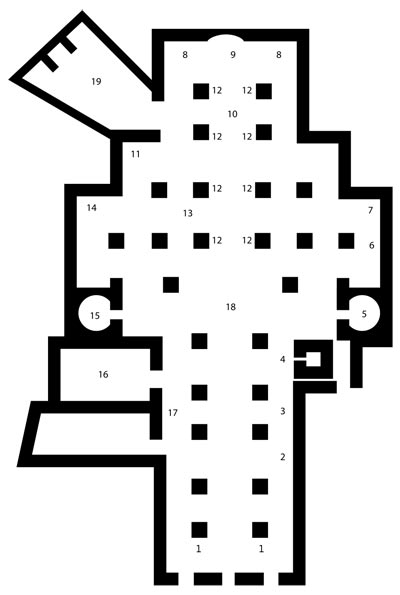

Plan of Siena Cathedral

1) Antonio Federighi Holy Water Stoups

2) Raffaello Vanni St. Francis de Sales

3) Pier Dandini Saint Catherine.

4) Bell Tower

5) Gian Luigi Bernini Madonna del Voto Chapel

6) Luigi Mussini Saint Crescentius

7) Alessandro Casolani Nativity

8) Wooden Choir

9) Duccio di Buoninsegna Stained Glass Window

10) Baldassare Peruzzi Main Altar

11) Donatello Bishop Pecci's Tomb

12) Domenico Beccafumi Angel Candelabra Holders

13) Nicola Pisano Pulpit

14) Francesco Vanni Saint Ansanus

15) Donatello St. John the Baptist

16) Piccolomini Library

17) Andrea Bregno Piccolomini Altar

18) Pavement

19) Sacristy

|

The current apse of the cathedral was extended in the direction of Vallepiatta in 1316 when construction began on the Baptistery. Later, around 1525, probably under the direction of the architect Baldassare Peruzzi, a large niche was opened in its center, which was frescoed by Domenico Beccafumi between 1535 and 1544. Of Beccafumi’s work, the Glory of Angels on the ceiling survives, while the triangle surrounded by rays of light in the middle of the fresco, a symbol of the Holy Trinity, was added later in 1812 by Francesco Mazzuoli, who replaced Beccafumi’s figure of Christ with the triangle. This intervention was a consequence of the disastrous earthquake which struck Siena in 1798 and destroyed the central part of the apse, making Mazzuoli’s restoration necessary. [ 2]

|

|

|

The baptistry, the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist (15) is situated in the left transept, underneath the eastern bays of the choir of the Duomo. The main attraction is the hexagonal baptismal font, containing sculptures by Donatello, Jacopo della Quercia and others, and eight frescoes by Pinturicchio, commissioned by Alberto Aringhieri, and painted between 1504 and 1505

.

At the back of this chapel, amidst a rich renaissance decorations, is the bronze statue of St. John the Baptist by Donatello.

Donatello, Saint John the Baptist (15)

This is a late work, made in Florence in 1457 and brought to Siena once it was finished. It is very similar in style and feeling to the Mary Magdalene now in the Opera del Duomo museum in Florence. The thin figure of Saint John exudes drama with his haggard face, sunken eyes, protruding veins, and bristly hair and beard. His half-open mouth and stunned, fixed stare give evidence of his deep suffering.

|

|

Vecchietta, frescoes of the Baptistry of the Cathedral of Siena, substantially repainted in the 19th century.

|

The Baptistery of San Giovanni was built between 1316 and 1325, under the direction of Camaino di Crescentino, the father of Tino di Camaino, to serve as the city's baptismal church. Unlike Florence or Pisa, Siena did not build a separate baptistry. The baptistry is located underneath the eastern bays of the choir of the Duomo, in the square with the same name.

Between 1447 and 1450, a series of frescoes were executed by Vecchietta and his pupils. They include depictions of the Evangelists, Prophets and Sibyls, the Four Articles of the Creed, and the Assumption. The frescoes were substantially repainted at the end of the 19th century. Vecchietta also painted two scenes on the wall of the apse: Flagellation and Road to Calvary.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

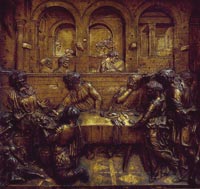

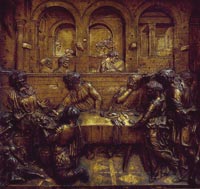

The main attraction of the baptistry is the hexagonal baptismal font, containing sculptures by Donatello, Jacopo della Quercia and others. The panel of The Feast of Herod is one of the great masterpieces of Renaissance sculpture. It was the first relief to be built in accordance with the rules of perspective.

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi, better known as Donatello, began his activity as an assistant to Ghiberti on the first set of doors for Florence Baptistery. He went on to work with Filippo Brunelleschi, with whom he went to Rome in the early years of the fifteenth century. Donatello’s art is distinguished by great expressive force, given artistic form in his use of ‘stiacciato,’a very low relief with which he manages to create profound depths of field, in strict accordance with Brunelleschian perspective despite the minimal difference between the planes.

The relief of Herod's Feast was executed by Donatello in 1425-1427. It is one of two panels originally ordered from Jacopo della Quercia for the baptismal fonts of Siena Cathedral. Here the architectural setting acts as one of the principal motifs of the scene. Possibly this setting was designed by Michelozzo. At any event it stands out in the history of art as the first relief to be built up in accordance with the rules of perspective. (...) This strict perspective layout and the network of straight lines structuring it, heighten the dramatic effect of the scene. Starting from the Baptist's severed head presented on a salver to the horrified Herod, arises the crescendo of rhythmed gestures conveying the emotional response of the figures, expressed already by contorted or spirited movements, by the restless animation of the drapery. The upsweep of her dress shows us Salome still dancing. The memory of her slender, buoyant figure lingers on in Lippi and Botticelli.[6]

|

|

Donatello, Feast of Herod,c. 1425

Baptistery, panel on the baptismal font, Siena |

| |

|

|

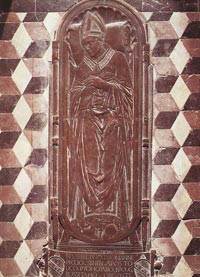

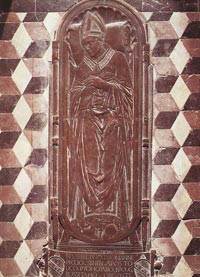

Tomb slab of Giovanni Pecci (1426-27)

Bishop Pecci's Tomb (11) is a masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance. According to the inscription, Giovanni Pecci, the bishop of Grosseto, died on 1 March 1426. The commission to design the bronze tombstone was presumably given to Donatello immediately afterwards. The perspective of the arrangement is such that the dead man does not –as one might expect– appear to be resting for eternity, but to be lying on a stretcher whose lower handles are still visible. Given Donatello's constant reformulation of and innovative changes to traditional artistic means of composition, the Pecci tombstone is another sign of his restless temperament.

The tomb cover was made of bronze and cast in three sections between 1426 and 1427 by Donatello himself. The work, signed OPUS DONATELLI, is, in Enzo Carli’s words, “a true gold-mine of perspectival solutions.” Despite the thinness of the bronze plate, an extraordinary effect of three-dimensionality distinguishes Bishop Pecci’s boots, the curl on his pastoral staff, the cushion on which he rests his head, and the cartouche held by two little angels. |

|

|

| |

|

|

The small Cappella della Madonna del Voto, the Chigi Chapel, is situated in the right transept. It is the last, most luxurious sculptural addition to the Duomo, and was commissioned in 1659 by the Sienese Chigi pope Alexander VII. This circular chapel with a gilded dome was built by the German architect Johann Paul Schor to the baroque designs of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, replacing a 15th century chapel. Two of the four marble sculptures in the niches, are by Bernini himself: Saint Jerome and Mary Magdalene.

Above the altar of the chapel is a painted panel depicting the Madonna and Child, called the Madonna del Voto by the Sienese. The painting is traditionally attributed by art historians to the painter Dietisalvi di Speme.

The Madonna del Voto is venerated even today and receives the tributes of the winning contrade every year. On the eve of the battle of Montaperti (Sept. 4, 1260) against Florence, the city of Siena dedicated itself to the Madonna. The victory of the Sienese, against all odds, over the much more numerous Florentines was attributed to her miraculous protection.

|

|

Dietisalvi di Speme, Madonna del Voto, Cappella Chigiana, Duomo di Siena

|

|

|

|

|

| Bernini, Mary Magdalene

|

| The Piccolomini library |

|

|

About halfway down the nave on the left is the entrance to the Piccolomini library (16), famed for its precious illuminated choir books and beautifully preserved Renaissance frescoes painted by Pinturicchio, based on designs by Raphael.[3]

The library was commissioned by Cardinal Francesco Piccolomini, Archbishop of Siena (later Pope Pius III), to honor the memory and book collection of his maternal uncle Enea (Aeneas) Piccolomini, who became Pope Pius II.

Pinturicchio painted this cycle of frescoes around the library between 1502 and 1507, representing Rafael and himself in several of them. This masterpiece is full of striking detail and vivacious colours. Each scene is explained in Latin by the text below. They depict ten remarkable events from the secular and religious career of pope Pius II. Pinturicchio's fresco cycle is a rare example of a unified decoration of the early sixteenth century. Well-suited to Pinturicchio's skills and to a somewhat provincial Siena, his lyric style fits comfortably into the medieval setting of the Cathedral.

Below these, glass cases hold large choir books illuminated in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries with elegant, beautiful miniatures. In the center of the room stands a sculpture group of the Three Graces, a Roman copy of a Hellenistic original, made in the third

century A.D.

Art in Tuscany | Pinturicchio | Frescoes in the Piccolomini Library of the Duomo in Siena

|

|

Pope Aeneas Piccolomini Canonizes Catherine of Siena (detail), with on the left presumed portraits of Rafael and Pinturicchio Pope Aeneas Piccolomini Canonizes Catherine of Siena (detail), with on the left presumed portraits of Rafael and Pinturicchio

Piccolomini Library, Duomo, Siena |

|

|

|

|

|

Portale della Libreria Piccolomini del Marrina, Siena Duomo

|

|

Libreria Piccolomini, affrescata da Pinturicchio

|

|

Biblioteca Piccolomini, affrescchi di Pinturicchio |

| |

|

|

|

|

The Piccolomini altar (17), left of the entrance to the library, is the work of the Lombard sculptor Andrea Bregno in 1483. The architectural and sculptural altarpiece was commissioned by cardinal Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini who expected it to become his tomb. However, he was elected Pope Pius III and was buried in the Vatican.

This altarpiece is remarkable because of the four sculptures in the lower niches, made by the young Michelangelo between 1501 and 1504 : Saint Peter, Saint Paul, Saint Gregory (with the help of an assistant) and Saint Pius. On top of the altar is the Madonna and Child, a sculpture (probably) by Jacopo della Quercia.

The central painting of the Madonna is by Paolo di Giovanni Fei and from the late 14th century.

|

|

|

| |

|

Andrea Bregno, altare Piccolomini, 1503 |

Domenico di Bartolo was an Italian painter of the Sienese School. He was born in Asciano. He was employed by Vecchietta in the masterpiece fresco The Care of the Sick in the Pellegrinaio (Pilgrim's Hall) of the Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala in Siena. In 1434, he painted a fresco panel of Emperor Sigismund Enthroned for the Siena Cathedral (Imperatore Sigismundo in trono). The Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund stayed in Siena on his way to Rome for his coronation. This panel is proof of his popularity by the Sienese. Domenico died in Siena around 1445.

Next to his panel, is the composition in 1447 (probably) by Pietro di Tommaso del Minella of the Death of Absolom (Morte di Assalonne).

The next panel dates from 1473: Stories from the Life of Judith and the Liberation of Bethulia (Liberazione di Betulia) (probably) by Urbano da Cortona.

|

|

|

The marble high altar of the presbytery (10) was built in 1532 by Baldassarre Peruzzi. The enormous bronze ciborium is the work of Vecchietta (1467-1472, originally commissioned for the church of the Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala, across the square, and brought to the cathedral in 1506. At the sides of the high altar the uppermost angels are masterpieces by Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1502).

The enormous bronze ciborium, also created by Vecchietta (Lorenzo di Pietro) for the Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala (c. 1467-72), was moved to the Cathedral of Siena in 1506, replacing Duccio's Maestà. According to Vasari, 'this casting, which is admirable, acquired very great fame and repute for him by reason of the proportion and grace that it shows in all its parts; and whosoever observes this work well can see that the design is good, and that the craftsman was a man of judgment and of practised ability.'[ 2]

|

|

Altar of the Cathedral of Siena by Baldassarre Peruzzi with bronze ciborium by Vecchietta, and bronze angels holding candelabra (upper pair by Domenico Beccafumi, lower pair by Francesco di Giorgio Martini) Altar of the Cathedral of Siena by Baldassarre Peruzzi with bronze ciborium by Vecchietta, and bronze angels holding candelabra (upper pair by Domenico Beccafumi, lower pair by Francesco di Giorgio Martini)

.

|

| The hexagonal dome is topped with Bernini's gilded lantern, like a golden sun. The trompe l'oeil coffers were painted in blue with golden stars in the late 15th century. The colonnade in the drum is adorned with images and statues of 42 patriarchs and prophets, painted in 1481 by Guidoccio Cozzarelli and Benvenuto di Giovanni. The eight stucco statues in the spandrels beneath the dome were sculpted in 1490 by Ventura di Giuliano and Bastiano di Francesco. Originally they were polychromed, but later, in 1704, gilded. |

| |

|

|

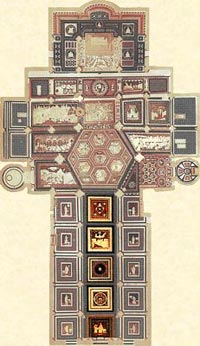

Mosaic floor

|

|

|

|

Siena Duomo, mosaic floor

|

The floor consists of 56 panels in different sizes. Most have a rectangular shape, but the later ones in the transept are hexagons or rhombuses. They represent the sibyls, scenes from the Old Testament, allegories and virtues. Most are still in their original state. The earliest scenes were made by a graffito technique: drilling tiny holes and scratching lines in the marble and filling these with bitumen or mineral pitch. In a later stage black, white, green, red and blue marble intarsia were used. This technique of marble inlay also evolved during the years, finally resulting in a vigorous contrast of light and dark, giving it an almost modern, impressionistic composition.

An important panel in the north transept is Matteo di Giovanni's Massacre of the Innocents (1481). The painter was worryingly preoccupied with this theme - his disturbing paintings can be seen in the Palazzo Pubblico and Santa Maria dei Servi.

The earliest panel was probably the Wheel of Fortune (Ruota della Fortuna), laid in 1372 (restored in 1864). The She-Wolf of Siena with the emblems of the confederate cities (Lupa senese e simboli delle città alleate) probably dates from 1373 (also restored in 1864). The Four Virtues (Temperanza, Prudenza, Giustizia and Fortezza) and Mercy (Misericordia) date from 1406, as established by a payment made to Marchese d'Adamo and his fellow workers. They ware the craftsmen who executed the cartoons of Sienese painters.

The first known artist, working on the panels, was Domenico di Niccolò dei Cori, who was in charge of the cathedral between 1413 and 1423. We can ascribe to him several panels such as the Story of King David, David the Psalmist and David and Goliath. His successor as superintendent, Paolo di Martino, completed between 1424 and 1426 the Victory of Joshua and Victory of Samson over the Philistines.

In 1480 Alberto Aringhieri was appointed superintendent of the works. From then on, the mosaic floor scheme began to make serious progress. Between 1481 and 1483 the ten panels of the Sibyls were worked out. A few are ascribed to eminent artists, such as Matteo di Giovanni (the Samian Sibyl), Neroccio di Bartolomea (Hellespontine Sibyl) and Benvenuto di Giovanni (Albunenan Sibyl). The Cumaean, Delphic, Persian and Phrygian Sibyls are from the hand of the obscure German artist Vito di Marco. The Erythraean Sibyl was originally by Antonio Federighi, the Libyan Sibyl by the painter Guidoccio Cozzarelli, but both have been extensively renovated. The large panel in the transept The Slaughter of the Innocents (Strage degli Innocenti) is probably the work of Matteo di Giovanni in 1481. The large panel below, the Expulsion of Herod (Cacciata di Erode), was designed by Benvenuto di Giovanni in 1484-1485. The Story of Fortuna, or Hill of Virtue (Allegoria della Fortuna), by Pinturicchio in 1504, was the last one commissioned by Aringhieri. This panel also gives a depiction of Socrates.

Matteo di Giovanni is best known for four monumental compositions of the Massacre of the Innocents, three for Sienese churches and one in inlaid stone for the pavement of the Duomo. The marble pavement is covered by infant corpses. Impassive courtiers flank Herod's throne, while the gloating king is portrayed as a monster: one hand is outstretched to order the butchery; the other, like a claw, clutches the marble sphinx on the arm of his throne.

Domenico Beccafumi, the most renowned Sienese artist of his time, worked on the floor during thirty years (1518-1547). Half of the thirteen Scenes from the Life of Elijah, in the transept of the cathedral, were designed by him (two hexagons and two rhombuses). The eight meter long frieze Moses Striking water from the Rock was executed by him in 1525. The bordering panel, Moses on Mount Sinai was laid in 1531. His final contribution was the panel in front of the main altar: the Sacrifice of Isaac (1547).[4]

Siena Duomo | The Mosaic floor and the Porta del Cielo in Siena Cathedral

|

|

|

|

Massacre (Slaughter) of the Innocents, by Matteo di Giovanni

|

A major highlight of the interior is the octagonal Gothic pulpit (13) by Nicola Pisano (1265-68), assisted by his son Giovanni and others. Four of the eight outer columns rest on lions, while the base of the central column is populated by the personified liberal arts. The seven marble panels depict the life of Christ in crowded scenes full of movement and life:

1. Annunciation, Visitation and Nativity

2. Journey and Adoration of the Magi

3. Presentation at the Temple and Flight into Egypt

4. Slaughter of the Innocents

5. Crucifixion

6. Last Judgment: Redeemed Souls

7. Last Judgment: Damned Souls

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Crypt is on the east side of the Duomo, accessed by a monumental flight of stairs on the south side (right side as you face the front of the cathedal).

The Crypt beneath the Duomo is a recently discovered gem with a series of 13th-century frescoes adorning its walls.

Despite its name and location, the Cripta is not exactly a crypt - it was never used for burials. It was constructed at the same time as the Duomo - in the 13th century - but Siena's citizens barely got a chance to enjoy its frescoes before it was filled with debris and abandoned. Expansion work on the choir beginning in 1317 required dismantling the crypt's vault, while the construction of the baptistery soon destroyed the facade. The crypt was subsequently used as a storeroom for construction materials and closed up for good. It lay unseen for nearly 700 years until its re-discovery during routine excavations in the Duomo in 1999. The room opened to the public in the fall of 2003.

The crypt is rectangular, bare and of little architectural interest, but there is a magnificent fresco cycle painted c.1270-80. Among the scenes that remain are the Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Kiss of Judas, Crucifixion, Deposition, and Entombment of Christ. The artists are not known for certain, but probably included Dietisalvi di Speme, Guido di Graziano and Rinaldo da Siena. They were most likely assisted by a young Duccio di Buoninsegna.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cripta del Duomo

|

|

Scuola senese, affrescchi, 1280 circa

|

|

Scuola senese, Annunciazione, 1280 circa

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cripta del Duomo di Siena, Annunciazione e Visitazione, 1280 circa

|

|

Deposizione dalla croce, 1280 circa, affresco, Siena, cripta del Duomo |

|

Scuola senese, Crocifissione, 1280 circa

|

Fresco of the Annunciation, Visitation and part of the Nativity (c.1280) in the "crypt" of Siena Cathedral. The large room was built and frescoed in the 13th century, abandoned in the early 14th century, and not rediscovered until 1999. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Located in the heart of the Maremma, in southern Tuscany, Podere Santa Pia sits alone on a spectacular, private and tranquil hillside setting with expansive open views over the Maremma hills. The house itself is an old 'podere' or farmhouse that dates back to the 19th century, now lovingly restored with many of the original details preserved.

Tuscan Holiday houses | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

Podere Santa Pia is embedded in the tranquility of the Tuscan country and let you enjoy great views of the Maremma. It is suitably located only 20 kilometers from the highway Grosseto - Siena. |

|

|

|

Frescoes in the Piccolomini Library of the Duomo in Siena by Pinturicchio | Web Gallery of Art

Activating the Effigy: Donatello's Pecci Tomb in Siena Cathedral | Geraldine A. Johnson, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 77, No. 3 (Sep., 1995), pp. 445-459.

[1] The contrade Lupa is situated to the north of the Piazza del Campo. Traditionally, the residents of Lupa were bakers.

Lupa's symbol is a female wolf nursing twins. Its colors are black and white, trimmed with orange. The she-wolf of this contrada refers to the legend that Siena was founded by Senius, the son of Remus who, along with his twin Romulus, was raised by a wolf. Because of this, Lupa's sister city is Rome.

[2]

Vasari's Lives of the Artists | The Life of Francesco di Giorgio Martini(1439-1502) and the Life of Lorenzo Vecchietto (ca. 1412-1480)

[3] The events in the life of Pintoricchio are closely linked to the political landscape of Perugia. He created paintings of such magnificent beauty and skill that his fame and eminence in artistic circles in Umbria was ensured.

But many consider his crowning achievement to be the stunning cycle of frescoes that illustrated the life of Enea Silvio Piccolomini, Pope Pio II, located in the Piccolomini library in Siena. Ambroggio Barocci designed the grandiose architectural structure and the draughts for the illustrated scenes were prepared by a young Raffaello; these details only serve to underline the greatness achieved by the Perugian painter.

In 1513 he retired, due to ill health, to the Sienan countryside, where he died on the 11th December.

|

|

|

[4] Domenico di Pace Beccafumi (1486–May 18, 1551) was an Italian Renaissance-Mannerist painter active predominantly in Siena. He is considered one of the last undiluted representatives of the Sienese school of painting, and the most brilliant exponent of Mannerist art in Siena. In Siena, he painted religious pieces for churches and of mythological decorations for private patrons. In addition to painting, he also directed the celebrated pavement of the cathedral of Siena from 1517-1544; a task that took over a century and a half. He made very ingenious improvements in the technical processes employed, and laid down scenes from the stories of Ahab and Elijah, of Melchisedec, of Abraham and of Moses.

Especially noteworthy among the bronze decorations and fittings in the cathedral are the beautiful Angels on the eight piers that proceed from the high altar to the nave. Vasari reports that Beccafumi cast the angels in bronze himself.

Domenico Beccafumi was in Rome as a young man, from 1510 to 1512, where he became familiar with the work of Raphael and Michelangelo. Even though he worked in Siena for most of his life, he traveled also to Florence, Genoa (where he encountered the elegant Raphaelesque style of Perin del Vaga), and Pisa (where he painted two canvases in the apse of the cathedral). Beccafumi’s art is characterized by imaginative design and draftsmanship and by subtle atmosphere and the play of light and shadow.

Lit. Domenico Beccafumi | www.operaduomo.siena.it |pdf

|

|

|

|

|

|

Painting in Siena | http://www.wga.hu/tours/siena/

In the earlier years of the 13th century Guido da Siena, despite his great obscurity, is regarded as sharing with Coppo di Marcovaldo the honour of founding the Sienese School. The real founder, however, of the Sienese school was Duccio di Buoninsegna. In his work the grace and humanity and the power of emotional expression of the figures dominated the hieratic style of the Byzantine tradition. His masterpiece - and the only work which can be attributed to him with certainty - is the great altarpiece of the Maestà (1308-1311), painted for Siena cathedral and now in the Opera del Duomo, Siena (parts of it are also in the National Gallery, London, the Frick Collection, New York, and the National Gallery, Washington). The Rucellai Madonna, formerly attributed to Cimabue but now considered Duccio's work, shows Florentine influence.

In the 14th century Siena, a Ghibelline stronghold having close ties with Naples, Milan and France (Avignon), became a centre of the refined, intellectual, courtly trend of which the art of Simone Martini (c. 1284-1344) is a typical example. Simone's first work was the Maestà in the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena (1315). His equestrian portrait of Guidoriccio da Fogliano 1328 recalls the epic poems of chivalry. Between 1320 and 1330 he painted frescoes in the chapel of St Martin in the lower church of S. Francesco at Assisi; in Naples he painted St Louis of Toulouse Crowning Robert of Anjou (1317); in 1339 he went to Avignon where he died in 1344. His finest work is perhaps the Annunciation in the Uffizi, Florence (1333). His last works, such as the Orsini Polyptych in the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp, were more dramatic and emotional and had an even more refined linearity. His chief follower was Lippo Memmi (active by 1317; d. c. 1356). (See a detailed description of Simone's art in Tour #8c.)

Pietro Lorenzetti (d. 1348) and more particularly his brother Ambrogio Lorenzetti (d. 1348) brought Giotto's influence to Sienese painting. Many of Pietro's powerful paintings show the influence of Duccio and of Simone Martini, for example: altarpiece in the church of Sta Maria della Pieve, Arezzo (1320); Carmelite Altarpiece (1329, Pinacoteca, Siena); Birth of the Virgin (1342, Opera del Duomo, Siena). While working on the frescoes in the Lower Church at Assisi he came under the influence of Giotto. Ambrogio Lorenzetti's best works are his frescoes of the Effects of Good and Bad Government (1337-1339, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena), which represent the zenith of naturalism in 14th-century Italian painting. (See a detailed description of the Lorenzetti's art in Tour #8d.) The last notable 14th-century Sienese painter was Barna da Siena (active middle of the 14th century).

In the 15th century the school of Siena, which had fallen behind, was faithful to its past: awareness of new trends, but used for non-realistic ends. The two leading painters were Sassetta (1392-1450) and Giovanni di Paolo (1403-1483). Sassetta's first known work is the now dissembled Altar of the Eucharist (1423), his most important work being the St Francis Altarpiece painted for Borgo S. Sepolcro (1437-1444) and now dispersed. The main works of Giovanni di Paolo are the panels of the life of John the Baptist (also dispersed). Matteo di Giovanni (1435-1495) and Francesco di Giorgio (1439-1501), architect, sculptor and painter, were more affected by Florentine influences.

In the 16th century Raphael's followers included Sienese artists, by birth or adoption: the decorator Baldassare Peruzzi and his friend Bazzi, known as Il Sodoma (d. 1549), who was also influenced by Leonardo. The most important Mannerist painter in Siena was Domenico Beccafumi (1485-1551); he had a highly personal style with intensity of emotion and use of shot colour as seen in the Birth of the Virgin, (Siena).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()