| |

|

|

| |

Frescoes

|

The walls were once covered in frescoes; the first were applied in 1360, the last about three centuries later. The first was the Crucifixion by Francesco Traini, in the south western side. Then, continuing to right, in the southern side, the Last Judgement, The Hell, The Triumph of Death and the Anacoreti nella Tebaide, usually attributed to Buonamico Buffalmacco. The cycle of frescoes continues with the Stories of the Old Testament by Benozzo Gozzoli (15th century) that were situated in the north gallery, while in the south arcade were the Stories of Pisan Saints, by Andrea Bonaiuti, Antonio Veneziano and Spinello Aretino (between 1377 and 1391), and the Stories of Job, by Taddeo Gaddi (end of 14th century). In the same time, in the north gallery were the Stories of the Genesis by Piero di Puccio.

On 27 July 1944, a bomb fragment from an Allied raid started a fire. Due to all the water tanks being controlled, the fire could not be put out in time, and it burnt the wooden rafters and melted the lead of the roof. The destruction of the roof severely damaged everything inside the cemetery, destroying most of the sculptures and sarcophagi and compromising all the frescoes.

After World War II, restoration work began. The roof was restored as closely as possible to its pre-war appearance and the frescoes were separated from the walls to be restored and displayed elsewhere. Once the frescoes had been removed, the preliminary drawings, called sinopie were also removed. These under-drawings were separated using the same technique used on the frescoes and now they are in the Museum of the Sinopie, on the opposite side of the Square.

The restored frescoes that still exist are gradually being transferred to their original locations in the cemetery, inside the cemetery, to restore the Campo Santo's pre-war appearance.

|

|

Leo von Klenze, The Camposanto in Pisa, 1858, New Pinacothek of Munich [5]

Over the centuries, the Camposanto became the cultural center of Pisa and the region. Many were buried there, and priceless Roman sarcophagi and statues, along with biblical relics, were housed there. The walls were completely decorated in immaculate frescos, and were beautiful beyond description. In short, the Camposanto was the one of the most important and priceless historical structures in all of Italy. The painting seen here shows how it looked.

On July 27, 1944, a wayward Allied bombs started a fire nearby that quickly spread to the Camposanto. The wooden rafters burst into flame and melted the lead on the roof, which dripped down and completely destroyed everything inside.

|

|

Buonamico Buffalmacco, Triumph of Death, fresco, (detail, lower left corner).

This section of the painting refers to the medieval tale of "The Three Living and Three Dead."

|

| |

|

|

The Camposanto Cemetery, near the Duomo (cathedral) and Leaning Tower, was constructed to consolidate the remains of people who were once buried throughout the Field of Miracles. Many of the tombs are decorated with fine sculptures and stone carvings. A number of ancient caskets can be found in the building.

The most remarkable fresco is the realistic The Triumph of Death, the work of Buonamico Buffalmacco. Somescholars attribute many of the huge frescoes of the Camposanto Monumentale in Pisa to Francesco Traini, including the Last Judgement, Inferno, Legends of the Hermits and, the famous Il Trionfo della Morte (the Triumph of Death). Francesco Traini was an Italian painter active between 1321 to 1365. [1] [2]

The Trionfo della Morte (after 1350) is considered one of the finest and most powerful artworks of the Trecento as it displays the merciless omnipresence of death. It represents- like the earliest examples of Totentanz paintings which were contemporary in Germany - as a reaction to the horrors of the black death in the late 1340s. The fresco, with its naturalistic details, shows direct influences of the Sienese masters, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

American historian Barbara Tuchman examined the Traini fresco and described it thus: "A scroll warns that 'no shield of wisdom or riches, nobility or prowess' can protect them from the blows of the Approaching One. "They have taken more pleasure in the world than in things of God." In a heap of corpses nearby lie crowned rulers, a Pope in tiara, a knight, tumbled together with the bodies of the poor, while angels and devils in the sky contend for the miniature naked figures that represent their souls.[3]"

The legend of the Encounter between the Three Living and the Three Dead as shown in the Triumph of Pisa, with the figures of the hermits and the admonishing monk makes clear which role the ascetics played in the busy Italian cities. They held a counter position against the material values of the world. In this fresco the monk acts as a mediator between the Three Living and Three Dead. He came down from the mountain to show a scroll with the following verse: 'What we are you will become'. That is his admonishment to the noble hunters, who have caught sight of the three lying corpses in putrefaction. In their faces there is the terrible fear that the people of the fourteenth century must have felt when faced with death. Artists, writers and churchman painted, composed and preached stories about the dead and death, in order to put across the message to the onlooker and the reader. All these messages differ in expression and show a variety of solutions. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Francesco Traini or Buonamico Buffalmacco, Triumph of Death, fresco (detail) Campo Santo, Pisa, 1330s |

| |

|

|

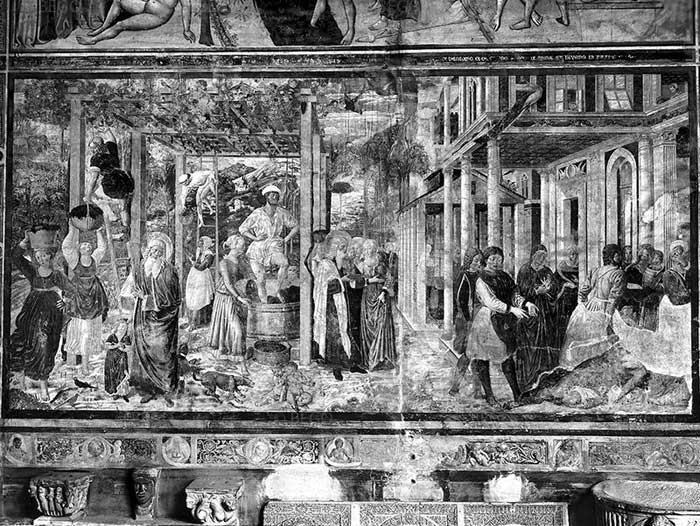

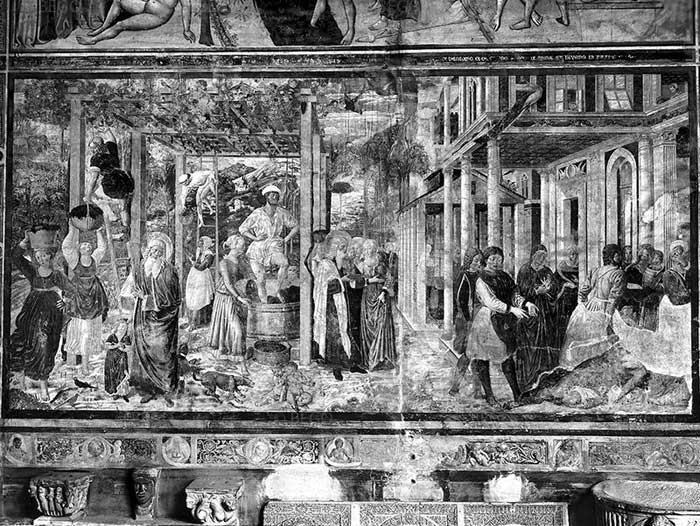

Benozzo Gozzoli, The Vintage and Drunkenness of Noah

|

|

|

| The frescoes that Benozzo Gozzoli painted for the Camposanto (Graveyard) of Pisa represent some of the most important works for understanding the ingenuity, excellence and ability of this painter, despite the fact that the paintings suffered irreparable damage during the bombardments of 1944.

Those who had the good fortune to admire them prior to this dramatic event could write that the frescoes of Benozzo seemed to make "that same leap that painting had made from Masaccio to Raffaello." Once again, this prolific artificer was defined "the Raffaello of the ancients."

In 1468, Benozzo began to paint twenty-six stories with episodes drawn from the old and the new Testaments on commission for the Opera Primaziale of Pisa - the lay institution that oversaw construction and preservation in Pisa. Two northern painters - Andrea Mantenga and Vincenzo Foppa - had already approached this entity in search of the prestigious assignment. Benozzo probably managed to obtain this job with the help of the Medici family's intervention (the arch-bishop of Pisa, Filippo di Vieri dei Medici, was a member of this powerful house).

Thanks to the precious incisions executed by Domenico Landini in the volume Pitture a fresco del Campo Santo di Pisa (Fresco paintings in the Camposanto (Graveyard) of Pisa), edited in Florence in 1812, and thanks to several photographs taken before the fire caused by a slug from an airplane in July of 1944, we can still get an idea of the paintings that Benozzo had frescoed on the west wall of the Camposanto (Graveyard) monument.

|

|

Benozzo Gozzoli, The Vintage and Drunkenness of Noah, Camposanto (Graveyard), Pisa.

|

| The layout and design of the scenes were imposed on Gozzoli by the previous pictorial decoration, begun in the mid-thirteenth century by Piero di Puccio and protracted until the end of the century, before being halted due to the political turmoil that was plaguing the city in those years. The painter subdivided the vast wall into two equal sections, each of which was partitioned into thirteen squares framed by a frieze decorated in antique style. Every story was accompanied by an inscription in common language, a sort of note that accompanied the figure that was depicted. Benozzo was skillful in coming up with inventive representations of these ancient stories, once again managing to translate the story into the daily context of his own times. Visitors to the prestigious Camposanto (Graveyard) monument, already a wonder of the peninsula during its own epoch, could recognize illustrious personalities and citizens of the times, in addition to complex, celebrated architectural works such as the Medici palace in Florence and the Pantheon of Rome.

|

|

The Curse of Ham, Camposanto (Graveyard), Pisa The Curse of Ham, Camposanto (Graveyard), Pisa

The Building of the Tower of Babel, Camposanto (Graveyard), Pisa The Building of the Tower of Babel, Camposanto (Graveyard), Pisa

|

| |

|

|

|

The Vintage and Drunkenness of Noah (photo 1890 approx.), Camposanto (Graveyard), Pisa

|

Following the terrible catastrophe, this entire series of frescoes - including Gozzoli's paintings along with those of several other artists of the thirteenth century (Spinello Aretino, Bonamico Buffalmacco, Andrea Buonaiuti, Taddeo Gaddi, Piero di Puccio, Francesco Traini, Antonio Veneziano, Francesco da Volterra) and fifteenth-sixteenth century (Paolo Guidotti Borghesi, Agostino Ghirlanda, Aurelio Lomi and Zaccaria Rondinosi) - were subjected to a protection and strappo (detachment) intervention that was unparalleled in the history of restoration.

For obvious reasons, these operations were conducted with great caution and in many cases employed new intervention techniques and materials which, only afterwards, were sometimes discovered to have been inappropriate for preserving the paintings: though some of the consequences are still visible today, the choices made at that time (the only possible ones for the epoch) succeeded in rescuing what remained of these splendid masterpieces. By the end of the 1950s, some of the paintings had already been restored and remounted on plasterboard frames and returned to Camposanto (Graveyard), while others (Trionfo della Morte/ The Triumph of Death , Giudizio Universale/The Last Judgment , Inferno/The Hell, Storie degli anacoreti/Stories of the Anchorites , Crocifissione/Crucifixion and Ascensione/Ascension) were exhibited in a specially-prepared hall adjoining the monument. While some paintings were still being detached from the original walls, the technicians noticed problems of preservation with the already detached frescoes - deterioration caused by casein, the binder used during the emergency restoration operations. Thanks to new experiences with restoration – pursuant, unfortunately, to damage caused by flooding in Florence – an innovative new technique involving the use of fiberglass panels had been developed. The painted surface was re-attached to a double layer of hemp canvas, using acrylic resin as a binding agent instead of casein. To oversee this complex operation, the Opera Primaziale Pisana formed a standing scientific commission (a commission had previously been united to decide the museum-ing of the paintings in new and specially-prepared sites) made up of experts in the sector, including Umberto Baldini, director of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure (literally meaning Workshop for Hard Stones) at the time. Intervention guidelines were established, and a rigorous study aimed to return the entire series of paintings to their original site. A ‘pilot worksite' was established on the West wall, where periodic testing confirmed the absence of problems linked to further deterioration. It was deemed advisable to continue with the systematization of the frescoes on the East wall and to formalize a technical-scientific Management team consisting of Umberto Baldini (deceased in 2006, replaced by Antonio Paolucci), Clara Baracchini and Antonino Calca. In recent years, this Committee has been continuously engaged with this complex restoration. During the organizing of the frescoes on the original walls, it was discovered that the Buffalmacco series, in exhibition since 1960 in the hall adjoining Camposanto (Graveyard), was suffering from various types of deterioration. Excluded from restoration until the last moment, it has recently been subjected to in-depth diagnostic testing to evaluate its state of preservation and identify new and more appropriate intervention techniques.

The frescoes of Benozzo Gozzoli, after careful restoration, will also be able to return to their original site. Since 2005, the scenes with the Vendemmia e l'ebbrezza di Noè ( Grape harvest and the inebriation of Noah ), the Maledizione di Cam (Curse of Ham) and, most recently, the episode of the Costruzione della Torre di Babele (Construction of the Tower of Babel) have all been relocated. By 2011, the entire Gozzoli series will once again be viewable along the north wall of the Camposanto (Graveyard) monument of Pisa.

|

Andrea di Bonaiuto | Scenes from the Life of St Rainerus

|

|

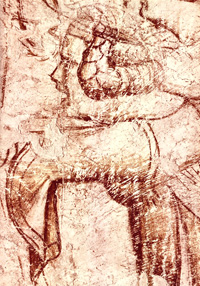

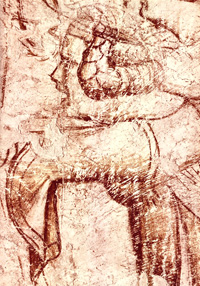

Andrea di Bonaiuto, detail of St. Ranieri in the Holy Land, Museo delle Sinopie, Camposanto, Pisa

|

Andrea di Bonaiuto is chiefly celebrated for his frescoes in the Spanish Chapel of Sta Maria Novella, Florence (1365-68), which was a Dominican church and the frescoes, illustrating the Triumph of the Faith, in their severity and their meticulous detail, rank among the most impressive records of Dominican art and thought produced in late medieval Italy.

Andrea is last recorded in 1377 working on frescoes of the Life of St. Ranieri in the Campo Santo at Pisa, and the three upper panels of this mural project are attributed to him.

Although he was acquainted with Giotto's innovations in modelling and spatial depth, Andrea was also strongly influenced by the linear, hieratic art of his Florentine contemporary Andrea Orcagna, and most of his fresco works display the rigid compositions and immobile faces associated with the Byzantine tradition.

Saint Rainerius (c1115/7-1160) is patron saint of Pisa and of travellers. |

|

Andrea di Bonaiuto, detail of St. Ranieri in the Holy Land, Museo delle Sinopie, Camposanto, Pisa Andrea di Bonaiuto, detail of St. Ranieri in the Holy Land, Museo delle Sinopie, Camposanto, Pisa

|

Piero di Puccio (di Giovanni) was a fourteenth century Italian painter of the Gothic period, active mainly in Orvieto. Between 1389 and 1391 Piero di Puccio was in Pisa, working on scenes from the Book of Genesis in the Camposanto. He painted a fresco of stories from Genesis, from the Creation to the Deluge on the North wall of Campo Santo.

These frescoes, on which his reputation and all attributions rest, reveal a monumental figure style combined with a highly developed vein of naturalism. The numerous and well-observed nudes in the Story of Adam and Eve testify to both, and the design of this densely populated fresco is typical of his lively narrative gifts and his comparative lack of interest in spatial recession. The Story of Noah is characterized by a multiplicity of genre detail and an elaborately geometrical articulation of the composition.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Interior of the Campo Santo in Pisa, c.1845 (w/c on paper), Italian School, (19th century)

Private Collection / © Charles Plante Fine Arts / The Bridgeman Art Library |

Benozzo in Pisa (1467-1495)

"Although almost completely destroyed during the bombings of 1944, Benozzo’s most important work in monumental terms remains the great mural cycle he painted between 1468 and 1484 for the Camposanto (Graveyard) in Pisa.

Even at that time, the Camposanto (Graveyard), where precious Roman sarcofagi co-existed with frescoes by the most renowned fourteenth-century painters, was considered one of the great wonders of Italy. It was said, in fact, that the earth in which the dead were laid to rest came from none other than Mount Calvary. The people of Pisa, well aware of this treasure, insisted that only a highly prestigious artist must be engaged to paint the twenty-six frescoes required to decorate it, demonstrating, once again, the high regard and esteem in which our painter was held.

In accordance with the custom of the time, Benozzo enlisted the help of numerous co-workers to complete this vast work, and this allowed him to take on new commissions. One of these was the altarpiece, dated 1470, produced (probably by his studio) for the main altar of the Church of San Lazzaro (Saint Lazarus) outside the walls, also commissioned by Pisa’s Opera Primaziale (the lay institution responsible for the construction of the Cathedral and Camposanto (Graveyard) monumental buildings, officially recognised in 1217), now housed in the institution’s museum. Others include the back of the Bishop’s chair in the Cathedral, now in the Louvre (a work of a highly doctrinal nature given its intended use and its depiction of the Triumph of Saint Thomas Aquinas, a subject very dear to the Dominican’s and the Church in general), and the small devotional altarpiece depicting the Madonna and Child with Saint Anne and donors, now housed in the Museum of St Matthew, originating from the Dominican convent of Santa Marta (Saint Martha).

In order to work on the Camposanto (Graveyard) site, Benozzo and his family moved to the ancient maritime republic of Pisa, buying a house near Piazza dei Miracoli (Square of Miracles). However, during the summer of 1479, due to the plague that raged all over Tuscany, the situation in Pisa had become critical. For this reason, the painter decided to relocate to the countryside outside Pisa, taking up residence in Legoli, a small outlying hamlet of what is now the municipality of Peccioli in the Era Valley. There, he worked on a magnificent tabernacle, frescoed on all four sides, which still stands at the entrance to the village. During his stay there, Benozzo was called to Volterra to decorate the chapel of the Virgin in the Cathedral. The chosen subject was the Procession of the Magi, which he set to work on assisted by his studio of artists.

Having returned to Pisa and completed the frescoes for the Camposanto (Graveyard), he received new engagements including a lost cycle recalled by Vasari in his Lives (1568), created for the nuns of San Benedetto in Ripa d’Arno. For the same church, he frescoed a niche with the Virgin with Saint John. This fresco has now been removed and is housed in the rooms of the old nunnery, now home to the Cassa di Risparmio (Savings Bank) of Pisa. During this same period, in around 1490, he painted the altarpiece depicting the Holy Conversation for these same nuns in Ripa d’Arno. The panel, now in a poor state of repair due to careless restoration work in the past, is housed in the San Matteo (Saint Matthew) National Museum in Pisa together with a Crucifixion and Saints frescoed for the refectory of the Dominican women’s convent. While perfectly settled in this city, which was proud to host him, Benozzo always maintained strong links with his home town of Florence. This patriotic love is clear from the way he consistently defines himself as "Florentine" in the inscriptions and signatures affixed to his works, and also manifested itself in his activities with the company of Florentines residing in Pisa, for whom he painted the altarpiece for the main altar of the chapel, now housed in the National Gallery in Ottawa.

During this second period in Pisa, according to the scholar Padoa Rizzo, Benozzo may also have produced the round-topped panel painting in the Parish of Calci, depicting the Virgin and Child, originating from the Dominican convent in Poggio."

Benozzo Gozzoli | Scenes from the Old and New Testaments | www.brunelleschi.imss.fi.it

The Opera Primaziale Pisana is also committed to making this complex and prestigious restoration intervention available for reference by publishing the ongoing results of its work on the internet. | www.opapisa.it

Johannes Tripps, A critical and historical corpus of Florentine painting. IV: Tendencies of Gothic in Florence, 7/1: Andrea Bonaiuti, Firenze, Giunti, 1996.

Piero di Puccio was a fourteenth century Italian painter of the Gothic period, active mainly in Orvieto. He is also known as Pietro di Puccio. He painted a fresco of stories from Genesis, from the Creation to the Deluge on the North wall of Campo Santo in Pisa. The fresco was devastated during the allied bombing during World War II. Farquhar, Maria (1855). Ralph Nicholson Wornum. ed. Biographical catalogue of the principal Italian painters. Woodfall & Kinder, Angel Court, Skinner Street, London; Digitized by Googlebooks from Oxford University copy on Jun 27, 2006. pp. page 136 | www.books.google.com

Buonamico Buffalmacco | Gli affreschi del Campo Santo

[1] Francesco Traini was an Italian painter who was demonstrably active from 1321 to approx. 1365 in Pisa and Bologna. He appears to have been a follower of Andrea Orcagna. There is only one work known to be by Traini: in 1345 he signed and dated a polyptych of the Pisan church S. Caterina, showing Saint Dominic and eight hagiographic scenes (now in the Museo Nazionale, Pisa).

Buonamico di [son of] Martino or Buonamico Buffalmacco (active c. 1315–1336) was an Italian painter who worked in Florence, Bologna and Pisa. Although none of his known work has survived, he is widely assumed to be the painter of a most influential fresco cycle in the Camposanto in Pisa, featuring the The Three Dead and the Three Living, the Triumph of Death, the Last Judgement, the Hell, and the Thebais (several episodes from the lives of the Holy Fathers in the Desert). Painted some ten years before the Black Death spread over Europe in 1348, the cycle - a "painted sermon" (L. Bolzoni) - enjoyed an extraordinary success after that date, and was often imitated throughout Italy. The youngsters' party enjoying themselves in a beautiful garden while Death piles mounds of corpses all around is likely to have inspired the setting of Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron, written a few years after the Black Death.

Boccaccio (in his Decameron) and Franco Sacchetti (in his Il trecentonovelle) both describe Buonamico as being a practical joker. Boccaccio features Buonamico along with his friends and fellow painters Calandrino and Bruno in several tales (Day VIII, tales 3, 6, and 9; Day IX, tales 3 and 5). Typically in these stories, Buonamico uses his wits to play tricks on his friends and associates: convincing Calandrino that a stone he possesses (heliotrope) confers invisibility (VIII/3), stealing a pig from Calandrino (VIII, 6), convincing the physician Master Simone of an opportunity to ally himself with the devil (VIII, 9), convincing Calandrino that he has become pregnant (IX, 3), convincing Calandrino that a particular scroll can cause a woman to fall in love with him (IX, 5). Throughout the stories, Buonamico is frequently depicted at work painting in the houses of notable gentlemen in Florence but eager to take time to eat, drink and be merry.

Giorgio Vasari includes a biography of Buonamico in his Lives, in which he tells several anecdotes about his comic escapades.[1] Vasari tells of Buonamico's youthful tricking of his master Tafi during his apprenticeship, various pranks and tricks that Buonamico played on his patrons, and his habit of embedding texts within his paintings. Dismissed by Vasari as just another of the witty painter's gags, which his "clumsy" contemporaries had misunderstood and foolishly imitated, the Camposanto frescoes are actually scattered with texts, a possible indication of the veracity of Vasari's remark. In the scroll over the cripple beggars in the center of The Triumph of Death, for instance, it says, "Since prosperity has completely deserted us, O Death, you who are the medicine for all pain, come to give us our last supper."

Vasari discusses various paintings by the artist which no longer exist, and many of which had already perished by the time of Vasari's writing in the sixteenth century. He describes a series of paintings at the convent of Faenza in Florence (already destroyed by the sixteenth century), works for the abbey of Settimo (now also lost), tempera paintings for the monks of the abbey of Certosa (also in Florence), and frescoes in the Badia at Florence. He describes a series of paintings depicting the life of Saint Catherine of Siena in a chapel in her honor in Assisi at the Basilica of Saint Francis (an attribution rejected by later scholars), and several prominent commissions at various abbeys and convents in Pisa. Interestingly, Vasari does not attribute the famed Pisan frescoes now associated with Buonamico to the painter, but rather, credits him with four frescoes at the Camposanto depicting the beginning of the world through the building of Noah's Ark, which later scholars have instead attributed to Piero di Puccio of Orvieto.

Vasari presents conflicting information regarding Buonamico's death, dating it to the year 1340, but also stating that he was still alive in 1351. In any case, he is said to have died at the age of 78, in poverty, and to have been buried at the hospital of Santa Maria Novella, in Florence.

[2] Buonamico di [son of] Martino or Buonamico Buffalmacco (active c. 1315–1336) was an Italian painter who worked in Florence, Bologna and Pisa. Although none of his known work has survived, he is widely assumed to be the painter of a most influential fresco cycle in the Camposanto in Pisa, featuring the The Three Dead and the Three Living, the Triumph of Death, the Last Judgement, the Hell, and the Thebais (several episodes from the lives of the Holy Fathers in the Desert). Painted some ten years before the Black Death spread over Europe in 1348, the cycle - a "painted sermon" (L. Bolzoni) - enjoyed an extraordinary success after that date, and was often imitated throughout Italy. The youngsters' party enjoying themselves in a beautiful garden while Death piles mounds of corpses all around is likely to have inspired the setting of Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron, written a few years after the Black Death.

The Triumph of Death, at the Camposanto in Pisa, has been puzzling generations of art historians. From G. Vasari to the twentieth century, the attribution and the date of this grandiose masterwork was very much a matter for debate. In Buffalmacco e il Trionfo della Morte L. Bellosi attributed the famous fresco beyond doubt to Buonamico Buffalmacco. He dates the artwork to about 1336. L. Battaglia Ricci in Ragionare nel Giardino studied the theme in correlation to Boccaccio's Decameron, pointing to the ten personages, seven women and three men, appearing in the gardens of the famous works of both Buffalmacco and Boccaccio. Thus, art historians have changed their view and approach in the understanding of this famous masterpiece appearing in the first half of the fourteenth century in Italy. Many scholars have been tempted to relate the famous Triumph of Death and paintings displaying the Dead and the Death to the Black Death in 1348, which devastated social life in Tuscany and other regions of Europe. When looking at these frescoes representing the Triumph of Death there is no doubt that medieval people felt death to be a drama. The plague may have given reason to personify death in its most dramatic nature, but this was not the case for having personified death in the shape of a woman armed with scythe and in the most vivid expression.

Ingrid Valser , The Theme of Death in Italian Art: The Triumph of Death, Department of Art History McGill University, Montréal, pp 59.

[3] The Triumph of Death Page about historian Barbara Tuchman's analysis of the Traini fresco in the Camposanto Monumentale, the Monumental Cemetry.

Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, 1978

"A strange personification of Death emerged from the plague years on the painted walls of the Camposanto in Pisa. The figure is not the conventional skeleton, but a blackcloaked old woman with streaming hair and wild eyes, carrying a broadbladed murderous scythe. Her feet end in claws instead of toes. Depicting the Triumph of Death, the fresco was painted in or about 1350 by Francesco Traini as part of a series that included scenes of the Last Judgment and the Tortures of Hell. The same subject, painted at the same time by Traini's master, Andrea Orcagna, in the church of Santa Croce in Florence, has since been lost except for a fragment. Together the frescoes marked the start of a pervasive presence of Death in art, not yet the cult it was to become by the end of the century, but its beginning.

Usually Death was personified as a skeleton with hourglass and scythe, in a white shroud or bareboned, grinning at the irony of man's fate reflected in his image: that all men, from beggar to emperor, from harlot to queen, from ragged clerk to Pope, must come to this. No matter what their poverty or power in life, all is vanity, equalized by death. The temporal is nothing; what matters is the afterlife of the soul.

In Traini's fresco, Death swoops through the air toward a group of carefree, young, and beautiful noblemen and ladies who, like models for Boccaccio's storytellers, converse and flirt and entertain each other with books and music in a fragrant grove of orange trees. A scroll warns that "no shield of wisdom or riches, nobility or prowess" can protect them from the blows of the Approaching One. "They have taken more pleasure in the world than in things of God." In a heap of corpses nearby lie crowned rulers, a Pope in tiara, a knight, tumbled together with the bodies of the poor, while angels and devils in the sky contend for the miniature naked figures that represent their souls. A wretched group of lepers, cripples, and beggars (duplicated in the surviving fragment of Orcagna), one with nose eaten away, others legless or blind or holding out a clothcovered stump instead of a hand,implore Death for deliverance. Above on a mountain, hermits leading a religious contemplative life await death peaceably.

Above in a scene of extraordinary verve a hunting party of princes and elegant ladies on horseback comes with sudden horror upon three open coffins containing corpses in different stages of decomposition, one still clothed, one half rotted, one a skeleton. Vipers crawl over their bones. The scene illustrates "The Three Living and Three Dead," a 13th century legend which tells of a meeting between three young nobles and three decomposing corpses who tell them, "What you are, we were. What we are, you will be." In Traini's fresco, a horse catching the stench of death stiffens in fright with outstretched neck and flaring nostrils; his rider clutches a handkerchief to his nose. The hunting dogs recoil, growling in repulsion. In their silks and curls and fashionable hats, the party of vital handsome men and women stare appalled at what they will become."

[4] Andrea di Bonaiuto (c. 1325–1379) was a respected and successful painter active in Florence after the black death. He is also known as Andrea da Firenze (but should not be confused with the composer Andrea da Firenze). Unfortunately, only a few archival entries refer to Andrea di Bonaiuto by name, and this of course hampers any attempt to reconstruct his career or personality.

Andrea matriculated in the Florentine painters’ guild in 1346. This would suggest a date of birth sometime around 1325. He lived in the parish of Santa Maria Novella and seems to have been influenced by the work of Nardo di Cione, with whom he may have trained. He left Florence in 1355 to work in Pisa, where he stayed for roughly ten years. When he returned to Florence, he received the most important painting commission of the 1360s.

In December 1365, Andrea accepted an offer to decorate the Dominican chapter house of Santa Maria Novella, built sometime around 1350 and funded in part by the estate of Buonamico di Lapo Guidalotti. To compensate Andrea, the Dominicans provided him and his wife with a house next to the church and a generous stipend. The agreement called for the artist to cover the four walls and the ceiling vaults of the chapter house with frescoes within a two-year period. Andrea appears to have met this deadline.

Probably as a result of this commission, Andrea was simultaneously appointed to a committee planning the design for the dome of the cathedral of Florence. He served on this board for two years, completing his term in 1367. He then spent a brief time in Orvieto before returning to Florence, where he painted a panel of Saint Luke for the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in 1374. In 1377, he accepted a commission to paint an altarpiece in Pisa, and then stayed in Pisa long enough to execute a fresco (now damaged) in the Camposanto. He died in 1379, leaving only a paltry estate for his widow and his one child, Bartolomeo.

Because almost none of his other works survive, Andrea’s murals in the chapter house of Santa Maria Novella, commonly referred to as the Spanish Chapel, stand as his greatest paintings. This cycle — probably based on ideas expressed by Fra Jacopo Passavanti of Santa Maria Novella — celebrates the spiritual and intellectual achievements of the founder of the Dominican Order and his disciples. The central image, on the north wall facing the entrance, depicts scenes from the passion of Christ. The Way to Calvary, Crucifixion, and Harrowing of Hell are placed in a continuous frieze running from one end of the lunette wall to the other. Flanking this space on the west wall is an image of Thomas Aquinas, enthroned, presiding over allegorical representations of the cardinal virtues and the liberal arts. The Via Veritatis decorates the east wall, with Dominic, Thomas, and Peter Martyr converting heretics, providing spiritual guidance to the devout, and leading the faithful into heaven. An architectural portrait of the cathedral of Florence, complete with an envisioned octagonal dome (the actual dome had yet to be constructed), serves as a backdrop to this scene; it may have been a result of Andrea’s membership on the committee planning the dome. Scenes of the Navicella, Resurrection, Ascension, and Pentecost occupy the vaults above, providing theological analogies to the images below.

The choice of Andrea di Bonaiuto as the painter of the Spanish Chapel suggests that he was one of the most important artists of the day; his appointment to the committee planning the dome of the cathedral indicates that he was highly respected by Florentine civic leaders. There can be no doubt that Andrea was recognized as a major figure in his native city during this period, and his works in Santa Maria Novella are one of the great decorative programs of the late Trecento. But the paucity of signed or dated paintings leaves us with only a meager understanding of the artist’s abilities, interests, and influences.

[5] Leo von Klenze (b. 1784 Schladen, Germany, d. 1864 Munich, Germany painter). An architect, painter, and writer, Leo von Klenze is most noted for his work as court architect to Ludwig I, king of Bavaria. He designed streets, squares, and numerous monumental buildings that set the scale and tone of Munich, the Bavarian capital. His other European commissions ranged from Athens, where he was the first to take steps to preserve the Acropolis, to Saint Petersburg, Russia. In addition to building, Von Klenze studied public building finance, designed and arranged museum galleries of ancient art, and was an accomplished painter. His paintings exhibit a richness of detail and special attention to light and compositional space. He successfully combined his talent for sharp observation with an equal and complementary ability to improve upon nature. On his visits to Italy, he both drew and painted landscapes and examined the remains of Greek temples as sources for his archaeological Greek style.

|

A sinopia is the name given to the sketch for a fresco made on the rough wall (prepared with arriccio) in a red earth pigment (called sinopia because it originally came from Sinope on the Black Sea). The sinopia was then gradually covered with grassello, another type of wet plaster, as work proceeded day by day on the fresco itself. By detaching a fresco from the wall it has been possible in many instances to recover the sinopia from the inner surface.

Restoration of the frescoes proved to be difficult, and it was the work of "strappo", the act of detaching a fresco from a wall in order to transfer it to a canvas or other support, which revealed the original design of the works of Buonamico Buffalmacco, Spinello Aretino, Antonio Veneziano, Andrea da Firenze, Taddeo Gaddi, Piero di Puccio and Benozzo Gozzoli,. Restored to their original beauty, the sinopie are the main attraction of the Museo delle Sinopie.

Museo delle Sinopie (Sinopie Museum, daily, summer, 10 am-8 pm, spring/autumn, 9 am-5:30 pm, winter, 9 am-5 pm, €5).

Located in the 13th-century Spedale di Santa Maria Chiara on the southern side of the square, the collection includes the original sketches, basic layouts and studies behind the creation of The Triumph of Death, The Last Judgment, Stories of the Anchorites and Benozzo Gozzoli's Biblical Stories, among others. It also offers a not-to-be-missed opportunity to see the spedale itself - the old hospital built here in 1258 to designs by Giovanni di Simone, as a gesture of penitence and obedience to Pope Alessandro IV. |

|

Buonamico Buffalmacco, Sinopia of one of the Damned in The Last Judgment |

Tuscany Holiday Homes | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden (June) |

|

Monte Christo, view from Santa Pia

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sant'Antimo, between Santa Pia and Montalcino |

|

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence |

|

Pisa |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Orvieto, Duomo |

|

Siena, Duomo |

|

Florence, Duomo Santa Maria del Fiore |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Damages to the artistic and historical heritage were considerable. Thousands of precious volumes from the National Library of Florence, were completely destroyed, and approximately 60 percent of Cimabue’s extraordinary Crucifix of Santa Croce was irreversibly lost.

Voluntaries of various nationalities, called “the angels of the mud,” came to Florence to save books and works of art from destruction. Frederick Hartt took a leave of absence to aid Florence, traveling throughout the United States to raise money to cover the cost of restoring damaged works of art as a board member of the Committee for the Rescue of Italian Art.

The “Monuments Men," were a group of men and women from thirteen nations, most of whom volunteered for service in the newly created MFAA section during World War II. Many had expertise as museum directors, curators, art historians, artists, architects, and educators. Their job description was simple: to protect cultural treasures so far as war allowed.

Deane Keller ( 1901-1992 )

From 1943 to 1946 Keller served as a MFAA officer with U.S. 5th Army in Italy, working to protect and salvage art and monuments at each location he visited. He sometimes arrived only hours after a town’s capture, witnessing the worst of the devastation and the despair of citizens. Keller, along with fellow MFAA officer Lt. Frederick Hartt, was part of the team that triumphantly returned the Florentine museum treasures to the city in 1945. Arguably his most valiant effort was made in Pisa at the ancient cemetery structure called Campo Santo. Inside the enormous Gothic building, which flanks the Pisa Cathedral opposite the Leaning Tower, frescoes made in the 14th and 15th centuries had been severely damaged from fire caused during the battle for the city. Keller quickly moved to save these artworks, bringing in a team to salvage and conserve as much of the frescoes as possible.

In 2000, Deane Keller was buried at Campo Santo in Pisa, in recognition of his extraordinary wartime efforts in Italy with honors from the United States, Italy, and the Roman Catholic Church.

Frederick Hartt (1914–1991)

Frederick Hartt was an American professor of History of Art at the University of Virginia. His books include Art: A History of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (two volumes) and Italian Renaissance Art, Michelangelo (Masters of Art Series), The Sistine Chapel and The Renaissance in Italy and Spain (Metropolitan Museum of Art Series).

Born in Boston, he received his PhD from New York University's Institute of Fine Arts in 1950. In World War II, Hartt was an officer in the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Division of the US Army and received a Bronze Star. He was also made an honorary citizen of Florence, and was decorated with the Knight's Cross by the Italian government.

The Monuments Men

Robert Morse Edsel(born 1956) is an American writer and the author of the non-fiction books, Rescuing Da Vinci, The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History and Saving Italy: The Race to Rescue a Nation's Treasures from the Nazis, about art treasures preserved during and after World War II and the heroes who saved them. Edsel is the founder and president of the Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art which received the 2007 National Humanities Medal and has donated two albums of photographic evidence of the Third Reich's theft of art treasures to the United States National Archives.

The Monuments Men, directed by and starring George Clooney

|

The Monuments Men is an upcoming American drama film co-written, produced and directed by George Clooney and starring Matt Damon, Clooney, Bill Murray, John Goodman, Jean Dujardin, Bob Balaban, Hugh Bonneville, and Cate Blanchett. Based on the book The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History by Robert M. Edsel, the film will concern the story of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program, an Allied group, tasked with saving pieces of art and other culturally important items before their destruction by Hitler during World War II.

On October 24, 2013, it was announced that the film would be released on February 7, 2014 at the 64th Berlin International Film Festival.

|

Read an excerpt from the book published by Hachette| pdf | www.monumentsmen.com

Documents and Photos | www.monumentsmen.com/documents

[1] Letter From 1st Lt Fred Hartt To Prof. Walter [Cook] Giving Account Of War Damage In Tuscany |

| |

This page uses material from the Wikipedia article Camposanto Monumentale, Francesco Traini, Buonamico Buffalmacco, Pisa, and The Monuments Men, published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pisa.

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Building of the Tower of Babel, Camposanto (Graveyard), Pisa

The Building of the Tower of Babel, Camposanto (Graveyard), Pisa