|

| Lamentation (Pieta) by the Master of Nerezi, 1164 |

|

The Byzantine Empire, founded when the capital of the Roman Empire was transferred from Rome to Constantinople in 324, existed in the eastern Mediterranean area until the fifteenth century. The arts and culture of this "New Rome" continued the pan-Mediterranean traditions of the late antique Greco-Roman world, setting the standard of cultural excellence for the Latin West and the Islamic East. Byzantine art is the term commonly used to describe the artistic products of the Byzantine Empire from about the 4th century until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. [1] Until the late eleventh century, southern Italy occupied the western border of the vast Byzantine empire. Even after this area fell under Norman rule in about 1071, Italy maintained a strong link with Byzantium through trade, and this link was expressed in the art of the period. Large illustrated Bibles ("giant Bibles") and Exultet Rolls—liturgical scrolls containing texts for the celebration of Easter, produced in the Benevento region of southern Italy—enjoyed great popularity from about 1050 onward. Miniature illustrations in the Bibles, which relate to contemporary monumental wall paintings produced in Rome, were strongly influenced by early Christian painting cycles from Roman churches. After the sack of Constantinople in 1204 by Christian armies of the Fourth Crusade, precious objects from Byzantium made their way to Italian soil and profoundly influenced the art produced there, especially the brightly colored gold-ground panels that proliferated during the thirteenth century. At the end of the thirteenth century and beginning of the fourteenth, three great masters appeared who changed the course of painting: the Florentine Giotto di Bondone (1266/76–1337), the Roman Pietro Cavallini (ca. 1240–after ca. 1330), and the Sienese Duccio di Buoninsegna (active ca. 1278–1318). Giotto's figures are volumetric rather than linear, and the emotions they express are varied and convincingly human rather than stylized. He created a new kind of pictorial space with an almost measurable depth. With Giotto, the flat world of thirteenth-century Italian painting was transformed into an analogue for the real world, for which reason he is considered the father of modern European painting. Duccio, founder of the Sienese school of painting, brought a lyrical expressiveness and intense spiritual gravity to the formalized Italo-Byzantine tradition.[2]

|

|

||

Just as the Byzantine empire represented the political continuation of the Roman Empire, Byzantine art developed out of the art of the Roman empire, which was itself profoundly influenced by ancient Greek art. Byzantine art never lost sight of this classical heritage. The Byzantine capital, Constantinople, was adorned with a large number of classical sculptures, although they eventually became an object of some puzzlement for its inhabitants. And indeed, the art produced during the Byzantine empire, although marked by periodic revivals of a classical aesthetic, was above all marked by the development of a new aesthetic. |

||

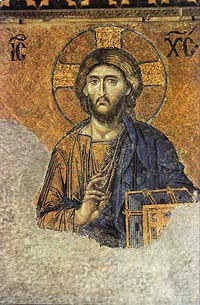

The subject matter of monumental Byzantine art was primarily religious and imperial: the two themes are often combined, as in the portraits of later Byzantine emperors that decorated the interior of the sixth-century church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. These preoccupations are partly a result of the pious and autocratic nature of Byzantine society, and partly a result of its economic structure: the wealth of the empire was concentrated in the hands of the church and the imperial office, which therefore had the greatest opportunity to undertake monumental artistic commissions.

|

||

|

||

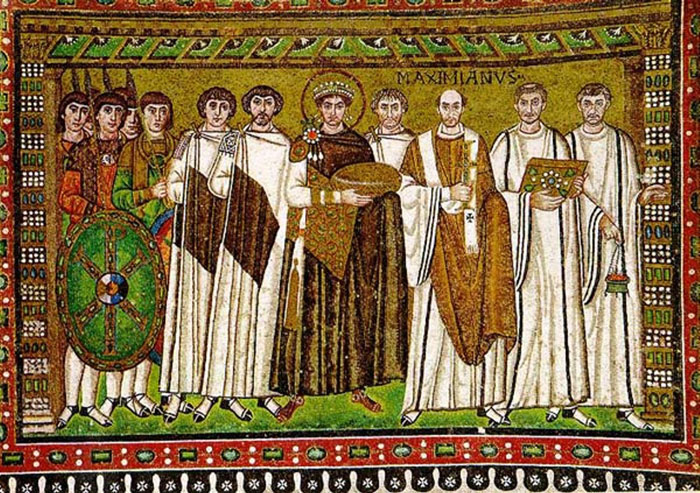

Mosaic of Justinian and Retinue at Apse Entry, San Vitale, Ravenna, c. 546 CE |

||

Early Byzantine art |

||

Two events were of fundamental importance to the development of a unique, Byzantine art. First, the Edict of Milan, issued by the emperors Constantine I and Licinius in 313, allowed for public Christian worship, and led to the development of a monumental, Christian art. Second, the dedication of Constantinople in 330 created a great new artistic centre for the eastern half of the Empire, and a specifically Christian one. Other artistic traditions flourished in rival cities such as Alexandria, Antioch, and Rome, but it was not until all of these cities had fallen - the first two to the Arabs and Rome to the Goths - that Constantinople established its supremacy. Constantine devoted great effort to the decoration of Constantinople, adorning its public spaces with ancient statuary,[10] and building a forum dominated by a porphyry column that carried a statue of himself.[11] Major Constantinopolitan churches built under Constantine and his son, Constantius II, included the original foundations of Hagia Sophia and the Church of the Holy Apostles.[12] The next major building campaign in Constantinople was sponsored by Theodosius I. The most important surviving monument of this period is the obelisk and base erected by Theodosius in the Hippodrome.[13] The earliest surviving church in Constantinople is the Basilica of St. John at the Stoudios Monastery, built in the fifth century.[14] Due to subsequent rebuilding and destruction, relatively few Constantinopolitan monuments of this early period survive. However, the development of monumental early Byzantine art can still be traced through surviving structures in other cities. For example, important early churches are found in Rome (including Santa Sabina and Santa Maria Maggiore),[15] and in Thessaloniki (the Rotunda and the Acheiropoietos Basilica).[16] A number of important illuminated manuscripts, both sacred and secular, survive from this early period. Classical authors, including Virgil (represented by the Vergilius Vaticanus[17] and the Vergilius Romanus[18]) and Homer (represented by the Ambrosian Iliad), were illustrated with narrative paintings. Illuminated biblical manuscripts of this period survive only in fragments: for example, the Quedlinburg Itala fragment is a small portion of what must have been a lavishly illustrated copy of 1 Kings.[19] Early Byzantine art was also marked by the cultivation of ivory carving.[20] Ivory diptychs, often elaborately decorated, were issued as gifts by newly appointed consuls.[21] Silver plates were another important form of luxury art:[22] among the most lavish from this period is the Missorium of Theodosius I.[23] Sarcophagi continued to be produced in great numbers. |

||

The Age of Justinian |

||

Significant changes in Byzantine art coincided with the reign of Justinian I (527-565). Justinian devoted much of his reign to reconquering Italy, North Africa and Spain. He also laid the foundations of the imperial absolutism of the Byzantine state, codifying its laws and imposing his religious views on all his subjects by law.[24] |

||

The seventh-century crisis |

||

|

||

7th-century mosaic from Hagios Demetrios (detail), Thessaloniki |

||

The Age of Justinian was followed by a political decline, since most of Justinian's conquests were lost and the Empire faced acute crisis with the invasions of the Avars, Slavs, Persians and Arabs in the 7th century. Constantinople was also wracked by religious and political conflict.[39] The most significant surviving monumental projects of this period were undertaken outside of the imperial capital. The church of Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki was rebuilt after a fire in the mid-seventh century. The new sections include mosaics executed in a remarkably abstract style.[40] The church of the Koimesis in Nicaea (present-day Iznik), destroyed in the early 20th century but documented through photographs, demonstrates the simultaneous survival of a more classical style of church decoration.[41] The churches of Rome, still a Byzantine territory in this period, also include important surviving decorative programs, especially Santa Maria Antiqua, Sant'Agnese fuori le mura, and the Chapel of San Venanzio in San Giovanni in Laterano.[42] Byzantine mosaicists probably also contributed to the decoration of the early Umayyad monuments, including the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Great Mosque of Damascus.[43] Important works of luxury art from this period include the silver David Plates, produced during the reign of Heraclius, and depicting scenes from the life of the Hebrew king David.[44] The most notable surviving manuscripts are Syriac gospel books, such as the so-called Syriac Bible of Paris.[45] However, the London Canon Tables bear witness to the continuing production of lavish gospel books in Greek.[46] The period between Justinian and iconoclasm saw major changes in the social and religious roles of images within Byzantium. The veneration of acheiropoieta, or holy images "not made by human hands," became a significant phenomenon, and in some instances these images were credited with saving cities from military assault. By the end of the seventh century, certain images of saints had come to be viewed as "windows" through which one could communicate with the figure depicted. Proskynesis before images is also attested in texts from the late seventh century. These developments mark the beginnings of a theology of icons.[47] At the same time, the debate over the proper role of art in the decoration of churches intensified. Three canons of the Quinisext Council of 692 addressed controversies in this area: prohibition of the representation of the cross on church pavements (Canon 73), prohibition of the representation of Christ as a lamb (Canon 82), and a general injunction against "pictures, whether they are in paintings or in what way so ever, which attract the eye and corrupt the mind, and incite it to the enkindling of base pleasures" (Canon 100). |

||

|

||

| The East Roman or Byzantine Empire was ruled by the Isaurian or Syrian dynasty from 711 to 802. The Isaurian emperors were successful in defending and consolidating the Empire against the Caliphate after the onslaught of the early Muslim conquests, but were less successful in Europe, where they suffered setbacks against the Bulgars, had to give up the Exarchate of Ravenna and lose influence over Italy and the Papacy to the growing power of the Franks. The dynasty however is chiefly associated with Byzantine Iconoclasm, an attempt to restore divine favour by purifying the Christian faith from excessive adoration of icons, which resulted in considerable internal turmoil.

At the end of the Isaurian dynasty in 802, the Byzantine Empire continued to fight the Arabs and the Bulgars for their very existence with matters made more complicated with the resurrection a Western Empire under Charlemagne. |

||

Iconoclasm |

||

Intense debate over the role of art in worship led eventually to the period of "Byzantine iconoclasm."[48] Sporadic outbreaks of iconoclasm on the part of local bishops are attested in Asia Minor during the 720s. In 726, an underwater earthquake between the islands of Thera and Therasia was interpreted by Emperor Leo III as a sign of God's anger, and may have led Leo to remove a famous icon of Christ from the Chalke Gate outside the imperial palace.[49] However, iconoclasm probably did not become imperial policy until the reign of Leo's son, Constantine V. The Council of Hieria, convened under Constantine in 754, proscribed the manufacture of icons of Christ. This inaugurated the Iconoclastic period, which lasted, with interruptions, until 843.

While iconoclasm severely restricted the role of religious art, and led to the removal of some earlier apse mosaics and (possibly) the sporadic destruction of portable icons, it never constituted a total ban on the production of figural art. Ample literary sources indicate that secular art (i.e. hunting scenes and depictions of the games in the hippodrome) continued to be produced,[50] and the few monuments that can be securely dated to the period (most notably the manuscript of Ptolemy's "Handy Tables" today held by the Vatican[51]) demonstrate that metropolitan artists maintained a high quality of production.[52] Major churches dating to this period include Hagia Eirene in Constantinople, which was rebuilt in the 760s following its destruction by an earthquake in 740. The interior of Hagia Eirene, which is dominated by a large mosaic cross in the apse, is one of the best-preserved examples of iconoclastic church decoration.[53] The church of Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki was also rebuilt in the late 8th century.[54] Certain churches built outside of the empire during this period, but decorated in a figural, "Byzantine," style, may also bear witness to the continuing activities of Byzantine artists. Particularly important in this regard are the original mosaics of the Palatine Chapel in Aachen (since either destroyed or heavily restored) and the frescoes in the Church of Maria foris portas in Castelseprio. |

||

|

||

Map Byzantine Empire 1025

|

||

Macedonian art |

|

|

Macedonian art (sometimes called the Macedonian Renaissance) was a period in Byzantine art which began with the reign of the Emperor Basil I of the Macedonian dynasty in 867. The period followed the lifting of the ban on icons (iconoclasm) and lasted until the fall of the dynasty in the mid-eleventh century. It coincided with the Ottonian Renaissance in Western Europe. In the ninth and tenth centuries, the Empire's military situation improved, and art and architecture revived. New churches were again commissioned, and the Byzantine church mosaic style became standardised. The best preserved examples are at the Hosios Lukas Monastery in mainland Greece and the Nea Moni Katholikon in the island of Chios. The very free frescoes at Castelseprio in Italy are linked by many art historians to the art of Constantinople of the period also. There was a revival of interest in classical themes (of which the Paris Psalter is an important testimony) and more sophisticated techniques were used to depict human figures.

Although monumental sculpture extremely rare in Byzantine art, the Macedonian period saw the unprecedented flourishing of the art of ivory sculpture. Many ornate ivory triptychs and diptychs survive, with the central panel often representing either deesis (as in the Harbaville Triptych pictured at right) or the Theotokos (as in a triptych at Luton Hoo, dating from the reign of Nicephorus Phocas). On the other hand, ivory caskets (notably the Veroli Casket from Victoria and Albert Museum) often feature secular motifs true to the Hellenistic tradition, thus testifying to an undercurrent of classical taste in Byzantine art. There are few important surviving buildings from the period. It is presumed that Basil I's votive church of the Theotokos of Phoros (no longer extant) served as a model for most cross-in-square sanctuaries of the period, including the monastery church of Hosios Lukas in Greece (ca. 1000), the Nea Moni of Chios (a pet project of Constantine IX), and the Daphni Monastery near Athens (ca. 1050). |

||

Comnenian Age |

||

The Macedonian emperors were followed by the Komnenian dynasty, beginning with the reign of Alexios I Komnenos in 1081.[2] Byzantium had recently suffered a period of severe dislocation following the battle of Manzikert in 1071 and the subsequent loss of Asia Minor to the Turks. However, the Komnenoi brought stability to the empire, (1081-1185), and during the course of the twelfth century their energetic campaigning did much to restore the fortunes of the empire. The Komnenoi were great patrons of the arts, and with their support Byzantine artists continued to move in the direction of greater humanism and emotion, of which the Theotokos of Vladimir, the cycle of mosaics at Daphni, and the murals at Nerezi yield important examples. Ivory sculpture and other expensive mediums of art gradually gave way to frescoes and icons, which for the first time gained widespread popularity across the Empire. Apart from painted icons, there were other varieties - notably the mosaic and ceramic ones. Nerezi frescoes are probably the best example of the Comnenian Age, and the big brake through of the Renaissance that developed within the Byzantine ... Some of the finest Byzantine work of this period may be found outside the Empire: in the mosaics of Gelati, Kiev, Torcello, Venice, Monreale, Cefalù and Palermo. For instance, Venice's Basilica of St Mark, begun in 1063, was based on the great Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, now destroyed, and is thus an echo of the age of Justinian. |

||

Palaeologan Age |

||

Eight hundred years of continuous Byzantine culture were brought to an abrupt end in 1204 with the sacking of Constantinople by the knights of the Fourth Crusade, a disaster from which the Empire never recovered. Although the Byzantines regained the city in 1261, the Empire was thereafter a small and weak state confined to the Greek peninsula and the islands of the Aegean.

Nevertheless the Palaeologan Dynasty, beginning with Michael VIII Palaeologus in 1259, was a last golden age of Byzantine art, partly because of the increasing cultural exchange between Byzantine and Italian artists. Byzantine artists developed a new interest in landscapes and pastoral scenes, and the traditional mosaic-work (of which the Chora Church in Constantinople is the finest extant example) gradually gave way to detailed cycles of narrative frescoes (as evidenced in a large group of Mystras churches). The icons, which became a favoured medium for artistic expression, were characterized by a less austere attitude, new appreciation for purely decorative qualities of painting and meticulous attention to details, earning the popular name of the Paleologan Mannerism for the period in general. Crete had been ruled by the Venetians since 1211, and the Cretan school of icon-painting gradually introduced Western elements into its style, and exported large numbers of icons to the West. After the fall of the Empire, Crete became the centre of Greek art, until it too fell to the Turks in 1669. |

||

The Byzantine era properly defined came to an end with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, but by this time the Byzantine cultural heritage had been widely diffused, carried by the spread of Orthodox Christianity, to Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania and, most importantly, to Russia, which became the centre of the Orthodox world following the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans. Even under Ottoman rule, Byzantine traditions in icon-painting and other small-scale arts survived, especially in the Venetian-ruled Crete and Rhodes, where a "post-Byzantine" style under increasing Western influence survived for a further two centuries, producing El Greco and other significant artists. The influence of Byzantine art in western Europe, particularly Italy was seen in ecclesiastical architecture, through the development of the Romanesque style in the 10th century and 11th centuries. This influence was transmitted through the Frankish and Salic emperors, primarily Charlemagne, who had close relations with Byzantium. The contribution of the migrated Byzantine scholars in Renaissance is also very important. |

||

| Berlinghiero Berlinghieri and his sons Bonaventura Berlinghieri (active 1228 – 74 ), Barone (active 1228 – 82 ), and Marco (active 1232 – 59 ). A family of Lucchese painters whose vigorously linear Romanesque idiom is often erroneously described as a Byzantine manner, reflecting its debt to Byzantine conventions. The static figures, devoid of contrapposto and with out-of-scale heads, on the Crucifix signed by Berlinghiero (Lucca, Mus. Nazionale di Villa Guinigi) would have been quite unacceptable to Byzantine patrons, but its imposing drawing undoubtedly influenced later pictorial technique in Tuscany. His son Bonaventura signed the most important early panel of S. Francis and his Life ( 1235 ; Pescia, S. Francesco), whose two-dimensional settings caricature Byzantine pictorial space, but with a vigorous chiaroscuro. Marco illuminated a Lucchese Bible in 1150 (probably Lucca, Bib. Capit., cod. 1) and was in Bologna, 1253 – 9 , where the mural of the Massacre of the Innocents in S. Stefano shows a related Italo-Byzantine idiom. The family workshop is also credited with an important mosaic of Christ and the Apostles on the façade of S. Frediano, Lucca, epitomizing their influence on painting in Tuscany between 1225 and 1275 . Berlinghiero Berlinghieri was the outstanding painter of thirteenth-century Lucca. The Madonna and Child — of exceptional beauty and importance — is one of only two that can be confidently assigned to him on the basis of comparison with a signed crucifix. Berlinghiero was always open to Byzantine influence, and this Madonna is of the Byzantine type known as the Hodegetria, in which the Madonna points to the Child as the way to salvation. Art in Tuscany | Bonaventura Berlinghieri |

||

John VIII Palaeologus was a Byzantine emperor (1421 – 48). When he acceded, the Byzantine Empire had been reduced by the Turks to the city of Constantinople. John sought in vain to secure Western aid by agreeing at the Council of Florence (1439) to the union of the Eastern and Western churches. His brother, Constantine XI, succeeded him in 1449 and was the last Byzantine emperor. The son of Manuel II Palaeologus, he was crowned coemperor with his father in 1408 and took effective control of the empire in 1421. He became sole emperor after his father's death in 1425. Of the diminished and fragmented empire, he ruled only Constantinople and the surrounding area. The city was besieged by the Ottoman Turks (1422), and, when Thessaloníki fell to Turkish forces (1430), John appealed to the West for help. He united the Byzantine and Latin churches (1439), but joint efforts against the Turks failed, and the Byzantines refused to submit to the pope. John died amid intrigues over succession. In 1439 the painter Benozzo Gozzoli was 19 when he watched the arrival in Florence of John VIII Palaeologus and his dignitaries to attend the Council of Florence. At this council terms were agreed for the reunion of the Catholic and Orthodox churches. It was a desperate attempt by the Byzantine Emperor to gain western support to counter-balance the Turkish threat. Gozzoli and all the Florentines were highly impressed by the rich costumes of the emperor and his followers and a few years later Gozzoli painted in Palazzo Medici a Magi's Procession which is actually the procession of John VIII Palaeologus, of the Patriarch of Constantinople and of another Byzantine prince at the Council of Florence (image in the background of this page). The silk dress of the emperor was most likely designed and manufactured in Mistrà, at the time a very flourishing town in Laconia, the region of southern Peloponnese which once was ruled by the Spartans. Portrait of of John VII Palaeologus as one of the Three Wise Men, by Benozzo Gozzoli. the bearded character on a white horse is the Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaiologos. The three girls next to him have been identified as the three daughters of Piero de' Medici, Nannina, Bianca and Maria. The middle king, accompanied by his pages and squires, is gazing upwards while riding through a hilly Tuscan landscape. He may be gazing at the Star of Bethlehem, which was possibly located in the left part of the destroyed entrance wall. The king is considered to be a portrait of Emperor John VII Paleologus. The identification is based on the assumption that the depictions reflect contemporary events. In this case it is thought to be a reference to the Council of Ferrara-Florence, in which the Emperor took part in 1439. The middle king is represented with the features of Emperor John VII Paleologus. For this representation Benozzo Gozzoli based his work on a medallion designed by Pisanello in 1438. However, he made the face younger and replace the traditional and unwieldy Byzantine tiara with a crown resting on a peacock-plumed velvet cap.[2]Art in Tuscany | Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Magi in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence |

|

|

Byzantium, Faith and Power, 1261-1453. Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2004) | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | www.metmuseum.org

|

||||

| [3] The influence of Byzantine art in western Europe, particularly Italy was seen in ecclesiastical architecture, through the development of the Romanesque style in the 10th century and 11th centuries. This influence was transmitted through the Frankish and Salic emperors, primarily Charlemagne, who had close relations with Byzantium. The contribution of the migrated Byzantine scholars in Renaissance is also very important. ' A comparison between two paintings of the same subject may clarify the novelty represented by the paintings of Giotto and justify the importance of his contribution to the Early Renaissance. The first painting is by an anonymous Byzantine artist, referred to as the Master of Nerezi: a fresco on the Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the Church of St. Pantaleimon, created in 1164 (Middle Byzantine period) located in Nerezi, Macedonia. The other represents the same subject as depicted by Giotto in 1304-1306, in the Capella degli Scrovegni, in Padua, Italy. The Master of Nerezi is undeniably able to transmit something of the pathos, the emotional dimension, of his subject, within the constraints of the Byzantine formal rules. In comparison to the early, strictly hieratic and solemn expression of the royal or Imperial-Christian art of Byzantium, there is here a more dynamic visual concept and action indeed: The Virgin Mary embracing the deposed Christ, the curved body of the disciple holding the hand of Christ, within a very briefly indicated location and schematic spatial setting. As Gombrich (The Story of Art) observed about the Byzantine style, within this basically two-dimensional formal concept in painting, we distinguish also the heritage of Greek and Hellenistic art, largely transformed but still recognizable. For example: skiagraphia, or “shadow painting”, was a system of tonal and color modulation employing mainly, according to some specialists, graphic elements such as cross-hatching. Its initial development was attributed to the Athenian painter Apollodorus (430-400 BCE). Skiagraphia aimed at optical effects, the creation the impression of solid and round bodies in space taking into account a subjective point of view. It survives in Byzantine painting as a conventionalized linear system of “patterned” anatomical representation. In contrast to the Pieta by the Master of Nerezi, Giotto’s figures are solidly articulated in themselves and among each other within a unified and coherent spatial setting. They not simply rest as patterns upon a surface, but occupy their own space and interact within the virtual space of the painted setting: the pictorially constructed box or stage. Two are the main sources, according to Gombrich, of Giotto’s accomplishment: classic (Roman) sculpture and the Christian plays publicly staged on different occasions in front of the churches, the theater as a traditional instrument of mass education and indoctrination in the Christian Church. In Giotto's Lamentation we recognize a tableau vivant or "staged picture" of representations of sacred narratives'. [Marcelo G. Lima] |

||||

| This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Byzantine Art and is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. | ||||

|

||||

The location of Podere Santa Pia is unique and the landscape a once-in-a-life sight.

|

||||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, December |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo |

||

Crete Senesi, surroundings of Podere Santa Pia |

Montefalco |

Florence, Duomo |

||

|

||||

The abbey of Sant'Antimo |

Cortona |

Spoleto, Duomo |

||

|

||||

Crete Senesi, surroundings of Podere Santa Pia

|

||||

| Podere Santa Pia is situated in the unspoiled valley of the Ombrone River, only 21 kilometres from Montalcino. This valley is famous locally as being of great natural beauty and still very undeveloped. Located between the Crete Senesi area and the Maremma, the Val d'Ombrone is synonymous with medieval villages, country walks and mountain bikes as well as being famous its wild mushrooms and its red wine. It is an ideal starting point to discover Tuscany. The guesthouse is located in Castiglioncello Bandini, a charming medieval village situated on a hill, which offers a spectacular view on the Alta Valle dell’Ombrone and the Maremma. Montalcino, the abbey of Sant'Antimo and Pienza are within easy reach. |

||||