|

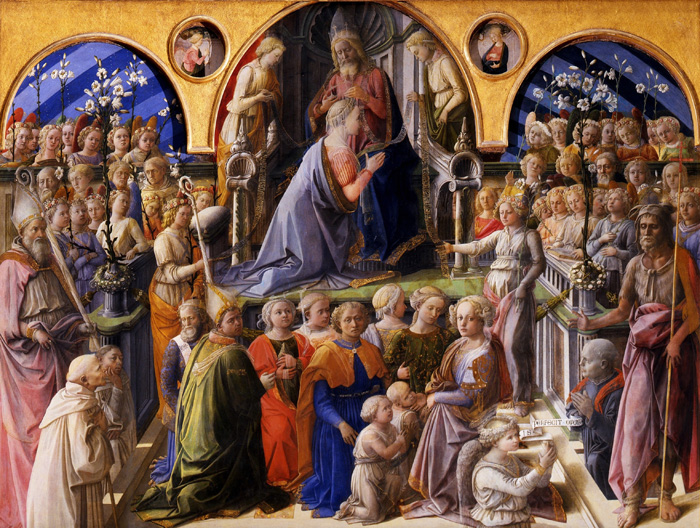

Fra Filippo Lippi, The Coronation of the Virgin, 1441-1447, 200 cm × 287 cm , Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze |

Fra' Filippo Lippi |

| Fra Filippo (di Tommaso) Lippi was one of the leading painters in Renaissance Florence in the generation following Masaccio. Influenced by him in his youth, Filippo developed a linear, expressive style, which anticipated the achievements of his pupil Botticelli. Lippi was among the earliest painters indebted to Donatello. His mature works are some of the first Italian paintings to be inspired by the realistic technique (and occasionally by the compositions) of Netherlandish pioneers such as Rogier van der Weyden and Jan van Eyck. Beginning work in the late 1430s, Lippi won several important commissions for large-scale altarpieces, and in his later years he produced two fresco cycles that (as Vasari noted) had a decisive impact on 16th-century cycles. He produced some of the earliest autonomous portrait paintings of the Renaissance, and his smaller-scale Virgin and Child compositions are among the most personal and expressive of that era. Throughout most of his career he was patronized by the powerful Medici family and allied clans. The operation of his workshop remains a matter of conjecture. |

||

| Fra' Filippo Lippi was born in Florence to Tommaso, a butcher. Both his parents died when he was still a child. Mona Lapaccia, his aunt, took charge of the boy. In 1420 he was registered in the community of the Carmelite friars of the Carmine in Florence, where he remained until 1432, taking the Carmelite vows in 1421 when he was sixteen.[1] In his Lives of the Artists, Vasari says: "Instead of studying, he spent all his time scrawling pictures on his own books and those of others." The prior decided to give him the opportunity to learn painting. Eventually Fra Filippo quit the monastery, but it appears he was not released from his vows; in a letter dated 1439 he describes himself as the poorest friar of Florence, charged with the maintenance of six marriageable nieces. In 1452 he was appointed chaplain to the convent of S. Giovannino in Florence, and in 1457 rector (Rettore Commendatario) of S. Quirico in Legania, and made occasional, considerable profits; but his poverty seems chronic, his money being spent, according to one account, in frequent amours. Vasari relates Lippi's visits to Ancona and Naples, nor of his capture by Barbary pirates and enslavement in Barbary, where his skill in portrait-sketching helped to release him.[2] From 1431 to 1437 his career is not accounted for. In June 1456 Fra Filippo is recorded as living in Prato (near Florence) to paint frescoes in the choir of the cathedral. In 1458, while engaged in this work, he set about painting a picture for the convent chapel of S. Margherita of Prato, where he met Lucrezia Buti, the beautiful daughter of a Florentine, Francesco Buti; she was either a novice or a young lady placed under the nuns' guardianship. Lippi asked that she might be permitted to sit for the figure of the Madonna (or perhaps S. Margherita). Under that pretext, Lippi engaged in sexual relations with her, abducted her to his own house, and kept her there despite the nuns' efforts to reclaim her. The result was their son Filippino Lippi, who became a painter no less famous than his father. Such is Vasari's narrative, published less than a century after the alleged events. |

Selfportrait of Fra' Filippo Lippi in the Incoronazione della Vergine, 1441-1447 Selfportrait of Fra' Filippo Lippi in the Incoronazione della Vergine, 1441-1447 |

|

In the “Coronation of the Virgin” Filippo Lippi has left us a portrait of himself at |

||

| Prato |

||

| At the peak of his fame, in 1452 Fra Filippo was asked by the City of Prato to fresco the main chapel of the Church of Santo Stefano, now the Cathedral, after Fra Angelico had turned down the offer. The frescoes in the choir of Prato cathedral, which depict the Stories of St John the Baptist and St Stephen on the two main facing walls, are considered Fra Filippo's most important and monumental works, particularly the figure of Salome dancing, which has clear affinities with later works by Sandro Botticelli, his pupil, and Filippino Lippi, his son, as well as the scene showing the ceremonial mourning over Stephen's corpse. This latter is believed to contain a portrait of the painter, but there are various opinions as to which is the exact figure. On the end wall of the choir are S. Giovanni Gualberto and S. Alberto, while the vault has monumental representations of the four evangelists. The composition of the scene is quite free, with a complex, imposing layout, and spaces dilated by an open perspective, in an original relationship between figures and setting. Where perspective is applied the form is not rigorous (often there are multiple vanishing points), and more importance is given to the theatrical effects and continuity of the story being narrated. The monumental conception of the figures (that according to Vasari makes Lippi the precursor of 16th century art and of Michelangelo), does not prevent them from being light, thanks to the liquid, luminous brushstroke and vaporous fabrics. The ability of Lippi to improvise and adjust the effect of the compositions directly while he worked meant that he often had to make additions (even whole groups of figures) to the finished parts of the fresco, painting over the dry plaster. Most of these additions have been lost in ancient attempts to clean the frescoes, while the dark lines that underline the hems, decorations and halos are applications in wax, and were originally covered in gold leaf.[3] Spoleto |

View of the right (south) wall of the main chapel |

|

The close of Lippi's life was spent at Spoleto, where he had been commissioned to paint, for the apse of the cathedral, scenes from the life of the Virgin. In the semidome of the apse is Christ crowning the Madonna, with angels, sibyls and prophets. This series, which is not wholly equal to the one at Prato, was completed by Fra Diamante after Lippi's death. That Lippi died in Spoleto, on or about the 8th of October 1469, is a fact; the mode of his death is a matter of dispute. It has been said that the pope granted Lippi a dispensation for marrying Lucrezia, but before the permission arrived, Lippi had been poisoned by the indignant relatives of either Lucrezia herself or some lady who had replaced her in the inconstant painter's affections. |

||

Madonna and Child Enthroned (Madonna of Tarquinia) (1437) -Tempera on panel, 151 x 66 cm, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome

|

||

| Nothing is known of Lippi's artistic origins and early style. The first information that can be offered falls into the 1430s. In 1432 Lippi probably painted a fresco in the cloister of Santa Maria del Carmine, the so-called Rules of the Carmelite Order, and in the same year he apparently left the convent permanently. A small cutdown painting of a Madonna and Child with Saints (in Empoli) has good claim to predate the Rules of the Carmelite Order and to be Lippi's. The picture is notably Masaccesque; recalling to a certain extent the central section of the Pisa Altarpiece, upon which Lippi may even have worked. Lippi was in Padua in 1434 and perhaps earlier, where he was recorded together with Francesco Squarcione, the local painter and powerful personality. Back in Florence, he signed and dated the Tarquinia Madonna in 1437 and obtained an important commission for an altarpiece, the Madonna Enthroned with Saints for the Barbadori family chapel in Santo Spirito, which he apparently finished during the following year. |

||||

| Madonna and Child Enthroned (Madonna of Tarquinia) (1437) |

||||

| The Madonna and Child Enthroned (also known as Madonna of Tarquinia) is housed in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica of Palazzo Barberini, Rome. The work, dated "A.D. M. MCCCCXXXVII" on the cartouche, was commissioned by Giovanni Vitelleschi, Papal military commander and archbishop of Florence. The painting was probably destined to his palace in his native city of Corneto (now Tarquinia). The centre of the composition is the face of the Madonna, who sits of a precious throne holding the Child. The attention to the volumes, inspired by Masaccio, is intermingled with the care for landscape and the light effects, which Lippi studied in the Flemish masters: the latter can be seen, for example, in details such as the pantoscopic view in the window on the left and the presence of precious objects. |

||||

| Madonna and Child with Saints (1438) |

||||

The earliest of Lippi's altarpieces, the Barbadori Altarpiece, named for the family who commissioned it (for the Barbadori Chapel in Santo Spirito, Florence), demonstrates aspects of his art that can be regarded as characteristic. He disregards perspective, tending to clutter the space with inventive but nonstructural architecture, while at the same time showing little interest in rendering his figures and the objects that surround them to a consistent scale. For example, the Virgin and the Child are quite large in size, much larger than the two saints before them, while the angels are an intermediate size. Lippi reverses, as it were, the spatial order. |

||||

| St. Jerome in Penance (c. 1439) |

||||

The St. Jerome in Penance, dating to c. 1439, is housed in the Lindenau-Museum of Altenburg, Germany. The work could be identified with the St. Jerome Penitent of which Lippi asked payment in a letter issued to Piero de' Medici in 1439.

|

||||

Triptych (c. 1437) |

||||

| The three panels formed a triptych which was painted in the 1430s in Florence by Lippi. Although made of three separate panels, the triptych was unified by a continuous wall and uniform lighting. It was probably commissioned for a convent or monastery. The side panels (now in the Accademia Albertina di Belle Arti, Turin) represent Sts Augustine and Ambrose (left) and Sts Gregory and Jerome (right), sized 129 x 65 cm each. The central panel (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) depicts the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Two Angels (123 x 63 cm). The central panel has been transferred from its original support, while the side panels have come down to us intact. |

||||

Triptych, c. 143, tempera and gold on wood, Accademia Albertina di Belle Arti, Turin and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

||||

In 1442, with Medici support, Pope Eugenius IV awarded Lippi an important benefice. A large payment was made in 1447 for St Bernard's Vision of the Virgin (National Gallery, London), produced for the Palazzo della Signoria, as well as final payments for the Coronation of the Virgin, made for Sant'Ambrogio, which was commissioned in 1441. |

||||

| Madonna and Child, c. 1440 |

||||

The composition of this painting evinces the characteristic features that were to make Lippi's half-length images so appealing. Foremost among these is the intimate confrontation effected between the viewer and the sacred subjects depicted. The pictorial space is very shallow and the Madonna and Child, painted on a large scale, are pushed up against the picture plane. The presence of the Virgin is made more tangible and imposing by her cast shadow falling in soft hues against the back of the stone niche, giving physical dimensions also to the compressed space. The Virgin meets the eyes of the beholder, who must have been positioned close to the panel in the more intimate viewing circumstances of theses tabernacle images. |

||||

| The Annunciation with two Kneeling Donors (c. 1440) |

||||

| The provenance of this panel has been connected to the Church of Sant'Egidio in Florence. At some point, the painting was probably cut down on the left side. On the basis of the hypothetical identification of the portrayed donors as Andrea and Lorenzo d'Ilarione de' Bardi, early scholars assumed that the picture could date to no earlier than 1452, and more likely to a bit later. Successive art historians have moved the painting to the early 1440's, comparing it to the Annunciation in Munich and recognizing in it the beginnings of Lippi's attachment to the style of Fra Angelico. The participation of Andrea del Castagno has also been suggested, with a date of around 1440. The portraits of the donors, more recently identified as Folco Portinari and Folgonaccio, were probably carried out with the help of an assistant. The composition pivots around the Virgin, who occupies the centre of the scene. In the background, on the right, two small figures of women are riding a stair. The two donor portraits show the unknown donors kneeling behind a cordonata. That they were represented in natural size (i.e., in the same size as the religious figures) was a relatively new stylistic feature. |

||||

| The Martelli Annunciation |

||||

| The Martelli Annunciation is a painting by Filippo Lippi, in the Martelli Chapel in the left transept of the Basilica di San Lorenzo, Florence. There is no information about the painting's origin, although it is likely that it was originally placed in the current location; the dating to c. 1440 is based on the style and the presence of St. Nicholas in the predella panels: this because Niccolò Martelli, a rich Florentine citizen which supported the reconstruction of the basilica during the Medici prominence in Florence. The painting is considered the very first knew example of squared altarpiece, without any traditional gothic decoration like pinnacles or cusps, in order to better match the simple architecture of the church, by Brunelleschi. The panel is divided in two by a central column. It uses geometrical perspective to show a complex architecture including several edifices and an open loggia. There are several elements suggesting the influence of Flemish painting, by which Lippi was influenced during his stay in Padua. These include the glass ampulla in the foreground, symbolizing the holy Spirit. On the left, over a step, is a group of angels, while on the right is the Annunciation scene, inspired to Donatello's Cavalcanti Annunciation (c. 1435). The angel is holding a white lily, a symbol of the Virgin's purity. The three scenes in the predella are similar to those in the Barbadori Altarpiece, from 1438. |

||||

| Portrait of a Man and a Woman, c. 1440 |

||||

This painting is, by common agreement, the first Italian portrait with a landscape background, and the first double portrait in Italian art. The sharply defined shadow cast by the male sitter onto the back wall probably relates to Pliny's well-known account of the origin of painting in the tracing of the contours of a cast shadow. |

||||

| Coronation of the Virgin (1441–1447) |

||||

| Lippi's second prominent altarpiece, the Coronation of the Virgin for the main altar of Sant'Ambrogio, was painted in the decade after the Barbadori Altarpiece. Commissioned for Sant'Ambrogio in 1441 and paid for in 1447, the Coronation of the Virgin contains a self-portrait of patron. Saint Ambrogio, the patron of the church, and Saint John the Baptist, the patron saint of Florence, dominate the sides of the composition. In the late 1430s, brother Filippo Lippi had left the convent of the Carmine convent to open an artist workshop of his own; however, having no money enough to pay assistants and apprentices, he worked alone with two usual collaborators, Fra' Carnevale and Fra' Diamante, along with an unknown "Piero di Lorenzo dipintore". The Coronation exhibits important innovations: the Baptist, gesturing toward the Virgin on the painting's central axis, introduces the spectator to the action. Behind him, still in the foreground, is the donor, while from below an angel enters the scene, a device that will find an echo later, in the art of Andrea Mantegna and in the frescoes of Domenico Ghirlandaio in the Sassetti Chapel of Santa Trinità. Little is left that specifically recalls Masaccio's solutions in these large paintings. Art in Tuscany | Filippo Lippi | The Coronation of the Virgin |

|

|||

| The Marsuppini Coronation (after 1444) |

||||

The Marsuppini Coronation is a painting of the Coronation of the Virgin, dating to after 1444. It is in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome. |

||||

| Annunciation, 1445-50 |

||||

The Annunciation, finished around 1445-1450, is housed in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome. The metaphor of light as a metaphysical vehicle, the allegorical significance of the heavenly communication that touches the Virgin on the shoulder, 'super brachium,' and is impressed like a seal, 'ut signaculum,' strongly stimulated the imagination of the painter, who was faced, like so many artists before and after him, with the insoluble problem of how to depict the conception of the Mother of God: "The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee" (Luke, 1, 35). |

Annunciation, Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome |

|||

| Seven Saints (c. 1449–1459) |

||||

| Seven Saints is a tempera on panel painting, dating to c. 1449–59, in the collection of the National Gallery, London. It is a pendant to Lippi's Annunciation, also in the National Gallery. The lunettes were commissioned as part of the decoration of the Palazzo Medici in Florence, where they were likely placed above a door or a bed. There is general agreement on Lippi's authorship of the panels, but their dating is less certain; they were produced some time between Lorenzo the Magnificent's birth in 1449 and the completion of the palace's furnishing in 1459. That their patron belonged to the Medici family is testified by the presence of Piero di Cosimo de' Medici's coat of arms in the other lunette, and by the link between the saints depicted in this panel and the male members of the family. Piero di Cosimo lived in Palazzo Medici from 1456. In the center is St John the Baptist, patron saint of Florence, flanked by the Saints Cosmas and Damian (protectors of the Medici, and in particular of Cosimo de' Medici, Piero's father). On the right, in the foreground, is St Peter of Verona, protector of Piero di Cosimo de' Medici, and next to him is St John the Evangelist, protector of his brother Giovanni. On the left, in the foreground, are St Francis of Assisi, the patron of Pierfrancesco the Elder (Piero's cousin), and St Lawrence, patron of his uncle, Lorenzo the Elder. Both lunettes were acquired just before 1848 from the Metzger brothers and introduced in the gallery in 1861. |

||||

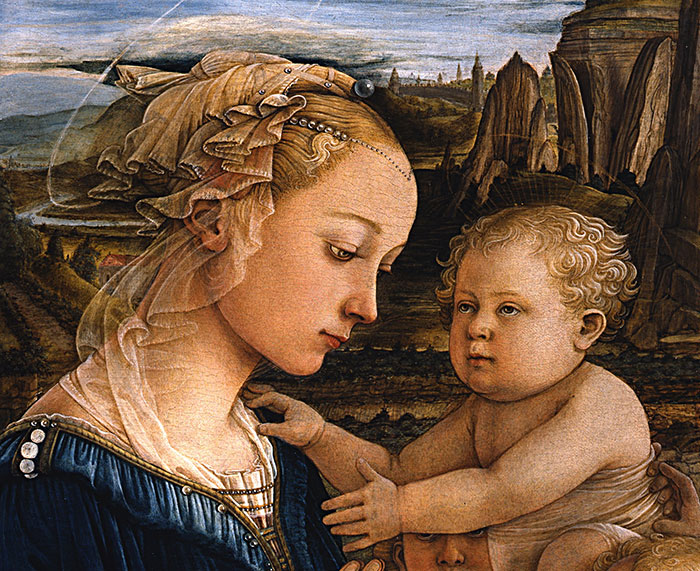

| Madonna and Child with Two Angels, ca. 1455 - 146 |

||||

|

||||

Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child with Two Angels, tempera on wood, ca. 1455 - 146, Firenze

|

||||

| Madonna with Child (Madonna col Bambino e angeli or Lippina) was executed around 1465. It is one of the few works by Lippi which was not executed with the help of his workshop and was an influential model for later depictions of the Madonna and Child, including those by Sandro Botticelli. The painting is housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Firenze. The commission and the exact execution date of the painting are unknown. The Madonna is traditionally identified with Lucrezia Buti (a nun and a lover of Lippi), thus ascribing the work to the period in which Lippi stayed at Prato (1452 - 1466). The unusual size is perhaps connected to a personal event, such as the birth of his son, Filippino (1457): however, if Filippino was chosen as model for the angel in the foreground, the panel could be from a date as late as around 1465. An 18th-century inscription in the rear of the panel testifies the presence of the painting in the Medici Villa del Poggio Imperiale at the time. On 13 May 1796 it entered the Gran Ducal collections in Florence, which formed the base of the future Uffizi museum. The group of Madonna and Child is, unusually for the period, placed in front of an open window beyond which is a landscape inspired to Flemish painting. The Madonna sits on a chair, and has an elaborate coiffure with a soft veil and pearls: this element was re-used in numerous late 15th century works in Florence, including the slightly later Portrait of a Young Woman by Andrea della Robbia in Museo del Bargello. Unlike previous similar works, the Child is held not by the Madonna, but by two angels, one of which, in the foreground, smiles towards the observer. The delicate swirls of transparent fabric that move around Mary's face and shoulders are a new decorative element that Lippi brings to Early Renaissance painting—something that will be important to his student, Botticelli. However, the pictorial modeling of Mary's form—from the bulk and solidity of her body to the careful folds of drapery around her lap—reveal Masaccio's influence.[] Sources: Fossi, Gloria (2004). Uffizi, Giunti Editore, 2004 |

|

|||

| Funeral of St. Jerome (c. 1452–1460) |

||||

| Stories of St. Stephen and St. John the Baptist (1452–1465) |

||||

| The frescoes of stories from St Stephen and St John the Baptist are considered to be among Fra Filippo Lippi's most important works. These two cycles of frescoes, painted on opposing walls at Prato Cathedral, are balanced. The birth of the saints face each other, the mid range mirrors their life work and their deaths are shown at the bottom. Perhaps the most famous scene is the Feast of Herod, a gruesome story depicted as a Florentine dinner party with the guests witnessing a beautiful dancer who ultimately presents her master with a severed head! 'The history of the chapel’s decoration has been reconstructed by various contributions, both critical and documentary. Among these, the conclusive work of Borsook (1975)—the culmination of a systematic research—which redefined the relationships between artists and patrons. The scholar demonstrated, in fact, that the numerous delays in completing the project were not attributable only to technical and administrative setbacks, but to new, demanding undertakings. |

|

|||

| The Madonna del Ceppo |

||||

| The Madonna del Ceppo was commissioned to Filippo Lippi him between 1452 and 1453. It is housed in the Civic Museum of Prato, Italy (though exposed in the local Museum of Wall Painting). The name derives from the fact it was located over a pit of the garden of Pia Casa dei Ceppi in Palazzo Datini, in Prato. It depicts, in the centre, the Madonna and Child flanked by St. Stephen and St. John the Baptist; below are Francesco Datini presenting to the Virgin the four Buonomini ("Honourable Men") of the Ceppo: Andrea di Giovanni Bertelli, Filippo Manassei, Pietro Pugliesi and Jacopo degli Obizzi. |

||||

| Madonna and Child of of Palazzo Medici-Riccardi (1966) |

||||

The Madonna of Palazzo Medici-Riccardi is housed in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi of Firenze. |

||||

| Madonna and Child (between circa 1446 and circa 1447), The Walters Art Museum |

||||

The Madonna della Cintola depicts the Madonna giving her girdle to St Thomas, with Sts Margaret (on the left, and perhaps a portrait of Lucrezia Buti), Gregory, Augustine, Raphael, and Tobias. There is a donor portrait of a kneeling nun, probably the abbess of Santa Margherita, a small Augustinian nunnery in Prato, where Fra Filippo was awarded the chaplaincy in 1456. |

||||

|

||||

Fra Filippo Lippi, The Madonna in the Forest (detail), c. 1460, oil on panel, 127 x 116 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin |

||||

| The Madonna in the Forest was made for the chapel of the Medici (later Medici-Riccardi) which decorated by Benozzo Gozzoli. It does not just depict the Adoration of the Child, it also shows the Holy Trinity. God the Father, the Holy Spirit and Christ are united on the painting and represent the conception of the Holy Trinity held by the Western Church: the Holy Spirit emanates from the Father and Son. This contrasts with the view held by the Orthodox Church, in which the Holy Spirit emanates from God the Father alone. The picture reflects the debate on general principles that took place between the Orthodox and Western Churches at the Council of Ferrara-Florence in 1439. The Madonna in the Forest was made for the chapel of the Medici (later Medici-Riccardi) Palace. Originally on the altar of the chapel, it was replaced with a copy in 1494. Art in Tuscany | Filippo Lippi | The Madonna in the Forest |

||||

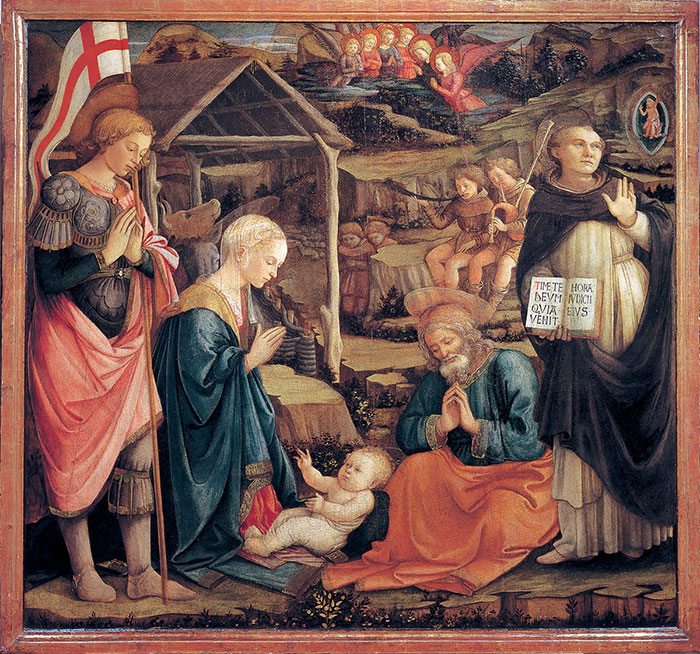

| Adoration of the Child with Saints, 1460-65 (Adoration of the Child with St. Vincenzo Ferrer)

|

||||

|

||||

| Adoration of the Child with Saints, 1460-65, panel, 146 x 157 cm, Museo Civico, Prato |

||||

The importance of Lippi's late period is revealed by this Nativity, set in a landscape in which a mental idea of the setting and not its real condition is projected. The painter produces a classical balance between plasticity and line. The extremely fine and elegant line softens the profiles and lessens the compactness of the forms.

|

||||

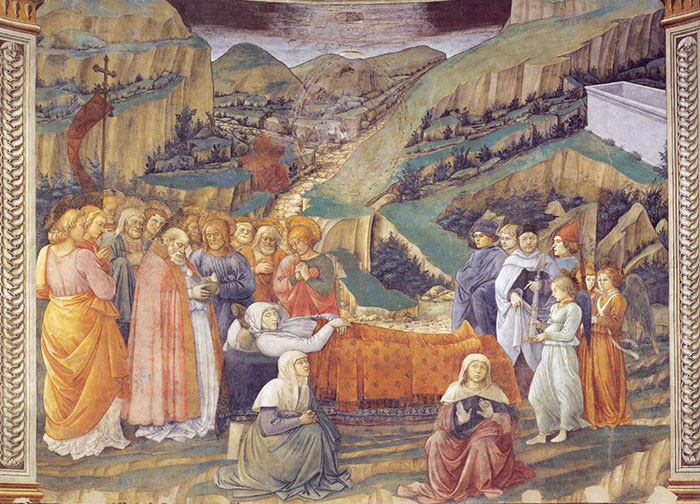

| Scenes of the Life of the Virgin Mary (1467–1469) - Fresco, apse of the Spoleto Cathedral |

||||

|

||||

| Death of the Virgin Mary (1467–1469), fresco, apse of the Spoleto Cathedral |

||||

Filippo Lippi started his last work, the fresco cycle Life of the Virgin, in September 1467 in the apse of the Spoleto Cathedral. The cycle remained incomplete at his death but were finished a couple of months later, in December 1469, by his son Filippino. The arrangement of the scenes is simple and symmetrical.

|

||||

|

||||

Filippo Lippi, The Presentation in the Temple, 1460-65, panel, 188 x 164 cm, Santo Spirito, Prato, with St Philip Benizi on the left and St. Pellegrino Laziosi (Latiosi) on the right.

|

||||

| In spite of his secular activities Fra Filippo's late works are infused with religious feeling and are far more lyrical than the early ones. The Madonna in the Forest in Berlin, the Adoration of the Child in Florence and Prato and the popular Madonna with the Child in Florence are examples. |

||||

. |

||||

| [1] Filippo Lippi". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. [2] Greene, Robert (2000). The 48 Laws of Power. Penguin Books. p. 187. ISBN 0-14-028019-7. |

||||

| [3] 'Lucrezia Buti, born in 1435 of Francesco Buti, a Florentine citizen, was sent to the Augustinian monastery of Saint Margaret in Prato by her family, where, along with her sister Spinetta, she was a “declared” sister beginning in 1454. It is probable that after the death of their father in 1450, the two girls were forced to take their vows – as often happened – by their brother Antonio, who remained as head of the large family of more than 11 people, just counting brothers and sisters. It was in the monastery that the fateful meeting occurred with Fra’ Filippo, who had been named chaplain of the convent at the beginning of 1456. Already well known for his weakness for female charms, the 50 year old Lippi was soon thunderstruck by the “beautiful looks and grace” of the young Lucrezia, and he convinced the nuns to let her pose for the panel he was painting for the monastery’s altar. This panel painting, today at the Civic Museum of Prato, represents ‘The Madonna giving Her Belt to Saint Thomas’ with Saints Gregory and Augustine, Tobias with the Angel, and Saint Margaret. Saint Margaret presents to the Virgin the donor of the painting, Sister Bartolommea del Bovacchiesi, the mother superior of the Convent. Probably the profile of Saint Margaret, much admired by Gabriele D’Annunzio, is the portrait of Lucrezia, which later figured in numerous madonnas of Lippi, among which is the celebrated ‘Lippina’ (c.1465) now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The love story, which had provoked so much scandal among their contemporaries, is recorded by Vasari himself: “And with this occasion (of the painting) he fell so in love, that he did so much through practical means, that he managed to take Lucrezia from the Nuns, and to take her away exactly on the day she was going to see the showing of the Belt of the Our Lady, the honoured relic of that city.” Lucrezia apparently had left the convent to attend one of the regular showings of the Sacred Belt and the two took advantage of the occasion to go and live together in his (Lippi’s) house. This was in 1457. The historical texts reveal also that her sister Spinetta and three other Nuns left the Convent to move into the house of Lippi, but they all returned to the monastery following the great scandal and the great shame that fell upon their innocent fellow nuns and the pressure of their families and the Church.[Source: Lucrezia Buti: the meeting with Fra’ Filippo | www.restaurofilippolippi.it] [4][Fonte: Restauro Filippo Lippi | www.restaurofilippolippi.it] References Public Domain This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press |

Filippo Lippi, Madonna della Cintola, Museo di Palazzo Pretorio (da Santa Margherita), Prato |

|||

|

||||

|

||||

| Death of the Virgin Mary (detail)(1467–1469), fresco, apse of the Spoleto Cathedral |

||||

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain, and uses material from the Wikipedia articles Filippo Lippi, Barbadori Altarpiece, St. Jerome in Penance (Fra Lippo Lippi), Madonna di palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Annunciation with two Kneeling Donors (Lippi), Madonna and Child (Filippo Lippi)(Sources: Fossi, Gloria (2004). Uffizi. Florence: Giunti,

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo |

||

|

||||

Montalcino |

Siena, duomo |

Choistro dello Scalzo, Florence |

||

|

||||

Spoleto, Duomo |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Florence, Duomo |

||

|

||||

Monte Amiata and the surroundings of Podere Santa Pia |

||||

Monte Amiata Monte Amiata, at 1,738 m, is the most important ski resort in southern Tuscany, situated in the Maremma between the valleys Val d'Orcia and Val di Chiana. |

||||