| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Hendrick Goltzius, Ritratto di Giambologna (particolare), 1591, Teylers Museum, Haarlem |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Giambologna, born as Jean Boulogne, incorrectly known as Giovanni da Bologna and Giovanni Bologna (1529 – 13 August 1608), was a sculptor, known for his marble and bronze statuary in a late Renaissance or Mannerist style.

The success and career of Jean de Boulogne, are based on a precise historical moment in mid-16th-century Florence. The establishment of the Medici family as rulers was an important feature of life in Florence, by the birth of an artistic historiography with the glorification of Michelangelo and by the relationship between artistic expression and the new criteria linked to the Council of Trent.

Flemish sculptor, Jean de Boulogne, who went on to become known as Giambologna at the Medici court, was able to bear all of these aspects in mind and to use them well to his advantage.

|

Giambologna was born in 1529, in Douai, which is now in France, although in the 16th century it was under the rule of Emperor Charles V, as was the rest of the area known as Flanders. As a child, he was apprenticed to the workshop of Flemish sculptor and architect Jacques Du Broeucq, maître-artiste de l'empereur who is also mentioned by Vasari. After youthful studies in Antwerp with the architect-sculptor Jacques du Broeucq,[1] he moved to Italy in 1550, and studied in Rome.

It was in the Flanders of Mary of Hapsburg, Queen of Hungary and Regent of the Netherlands, Jean became enamoured of contemporary Italian art and its evident classical roots.

In fact, the young Jean was greatly influenced by a long period spent in Rome, where he moved in 1550.

In Rome he was able to study the ancient statues and works by Michelangelo and from the school of Raphael directly. After a couple of years in the Urbe, during which he spent time perfecting his craft by making clay or wax models, taken above all from the themes of classical sculpture; one such piece is said to have been on the end of the negative opinion of an extremely severe and now elderly Michelangelo.

In Rome, Giambologna met with fellow countryman Willelm Tedrode and through this talented northern sculptor, already an assistant to Cellini - with the famous Guglielmo della Porta.

Some time around 1552, Jean de Boulogne moved from Rome to Florence, where he entered into partnership with Bernardo Vecchietti, his pygmalion and first means of introduction to the court of Duke Cosimo and that of his son, Francesco de'Medici.

|

|

Hendrick Goltzius, Ritratto di Giambologna, 1591, Teylers Museum, Haarlem Hendrick Goltzius, Ritratto di Giambologna, 1591, Teylers Museum, Haarlem

|

Giambologna made detailed study of the sculpture of classical antiquity. He was also much influenced by Michelangelo, but developed his own Mannerist style, with perhaps less emphasis on emotion and more emphasis on refined surfaces, cool elegance and beauty. Pope Pius IV gave Giambologna his first major commission, the colossal bronze Neptune and subsidiary figures for the Fountain of Neptune (the base designed by Tommaso Laureti, 1566) in Bologna. Giambologna spent his most productive years in Florence, where he had settled in 1553. Ten years later, he was named a member (Accademico) of the prestigious Accademia delle Arti del Disegno, just founded by the Duke Cosimo I de' Medici, at 13 January 1563, under the influence of the painter-architect Giorgio Vasari, becoming also one of the Medici most important court sculptors. He died in Florence at the age of 79 - the Medici had never allowed him to leave Florence, as they rightly feared that either the Austrian or Spanish Habsburgs would entice him into permanent employment. He was interred in a chapel he designed himself in the Santissima Annunziata.

Work

Giambologna enjoyed great popularity as a maker of garden sculpture for the Boboli Gardens, Florence (Fountain of Oceanus, 1571–76; Venus of the Grotticella, 1573), and for the Medici villas at Pratolino (the colossal Apennine, 1581), Petraia, and Castello. |

|

|

|

| |

|

The Appennine Colossus

|

|

|

|

Giambologna, the Appennine Colossus detail), Villa Pratolino, garden

|

Villa Demidoff is the current name of the ancient Medicean Villa of Pratolino. Located on the Florentine hills along the Via Bolognese heading into the Mugello valley, the estate in Pratolino was bought by Francesco I de' Medici in 1568.[7]

Legend has it that Francesco bought it as a gift for his second wife Bianca Cappello with the idea of turning it into a fairy-tale property. The architect chosen to build the villa and turn this wild area into a dreamy place was Bernardo Buontalenti. He built a splendid Renaissance villa, which unfortunately is no longer in existence, surrounded by a wonderland park with water fountains and grottoes, beautiful gardens filled with exquisite plants and flowers.

Most of this marvelous garden was destroyed in 1819 to make an easy to maintain "English garden". Only a few elements, including the gigantic statue of Appenine, survive from what was once the most celebrated garden in Europe. But Cupid's Grotto, a chapel, a series of crayfish pools and Giambologna's Appennine Colossus remain, brooding still, in the woods of what is now the Parco Demidoff.

As can be seen from the rough workmanship, the model is one of the first designs for the famous colossal sculpture, Apennine, monumental personification of the mountain chain or rather, of a great river; a giant represented as kneeling on a pond in the Medici villa of Pratolino. The head, which is steeped in water and mud, is bent down, following the vigorous movement of the shoulders. This seems to allude to a superhuman being, released from the rocks and the ground and about to get up and enter into action above something.

|

|

Appennine Colossus, Giambologna, 1579-1580, Parco Mediceo di Pratolino, Vaglia

|

Flying Mercury andother famous bronzes by Giambologna

|

|

|

Giambologna became well known for a fine sense of action and movement, and a refined, differentiated surface finish. Among his most famous works are the Mercury (of which he did four versions), poised on one foot, supported by a zephyr. The god raises one arm to point heavenwards, in a gesture borrowed from the repertory of classical rhetoric[2] that is characteristic of Giambologna's maniera.

'The Mercury shows a life-sized figure of a sleek youth, created as he takes flight, a young god with his right arm pointing upwards: a lively, superhuman action, a stupefying surge that commences with the blowing wind, Zephyr, and finishes in the elegant movement of the index finger, pointing up to the sky, a place of true wisdom and also of divine protection.

This Mercury dates back to 1580 and until 1780, it decorated the Villa Medici Roma, where Ferdinando de' Medici had wanted it to crown a fountain in breccia stone at the centre of a stairway between the sumptuous gardens and the entrance loggia to the main building. However, the creation itself dates back to 1563, when Bishop Pier Donato Cesi, papal delegate, requested Giambologna to create a Mercury coming down from the heavens for the Archiginnasio in Bologna. This commission did not come to fruition but it was followed by Duke Cosimo, who sent sculptures by Giambologna as gifts to Maximilian II, father of his daughter-in-law Joanna of Austria. These included a Mercury in flight to please the Emperor. On this subject, a medallion cast in 1551 by Leone Leoni for the Hapsburg Emperor, provided an initial idea for Giambologna, together with more general references to the style of Cellini. With technical daring, Jean Boulogne translated this perfect idea for a relief design into three-dimensional versions of different sizes.'[5]

Giambologna's several depictions of Venus established a canon of proportions and set models for the goddess's representation that were influential for two generations of sculptors, in Italy and in the North. He created allegories strongly promoting Medicean political propaganda, such as Florence defeating Pisa and, less overtly, Samson Slaying a Philistine, for Francesco de' Medici (1562).[3]

He delighted in solving the complex spatial problems of three intertwined figures in his famous Rape of the Sabine Women (1574–82). The subject was not finally determined until after it had been set up in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence's Piazza della Signoria. Heracles beating the Centaur Nessus (1599) is also a conscious tour de force.[4] It is also in the Loggia dei Lanzi.

|

|

Giambologna, Mercury, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Firenze

|

His ability to create natural forms in his sculptures made Jean de Boulogne famous for his representations of animals.

In 1563 Giambologna was called to Bologna. Here, at the orders of Pope Pius IV and his delegate Pier Donato Cesi, he created his first masterpiece, the monumental Fountain of Neptune in Piazza Maggiore; a pyramid-shaped group of sculptures and architecture dominated by Neptune, the god of the sea.

However, it was his Rape of the Sabine Women, put on public display in the setting of the Loggia della Signoria (Loggia dei Lanzi) that consecrated his success as a sculptor. His ability to sculpt bodies in the old classical style but rich with a beauty apparently close to natural forms, increased his fame, for example, in the invention of splendid figures of naked women in seductive poses but academically innovative and true to life.[5]

|

Sculptures in Loggia dei Lanzi

|

|

Loggia della Signoria or dei Lanzi

|

The Rape of the Sabine Women and Hercules Fighting the Centaur Nessus

|

|

|

The Rape of the Sabine Women is an episode in the legendary history of Rome, traditionally said to have taken place in 750 BC,[1] in which the first generation of Roman men acquired wives for themselves from the neighboring Sabine families.[6] The right arch in the Loggia della Signoria is dominated by the so-called Rape of the Sabine Women, a technical masterpiece by Giambologna. The artist did not originally intend to sculpt the legendary episode from early Roman history with the rape of the Sabine women by Romulo's companions; his intention was to create just three interacting figures in movement: a mature man, a youth and a beautiful woman, taken by the younger man from the weaker, older one.

Originally intended as nothing more than a demonstration of the artist's ability to create a complex sculptural group, its subject matter, the legendary rape of the Sabines, had to be invented after Francesco I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, decreed that it be put on public display in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Piazza della Signoria, Florence. True to mannerist densely-packed, intertwined figural compositions and ambitious overinclusive efforts, the statue renders a dynamic panoply of emotions, in poses that offer multiple viewpoints. When contrasted with the serene single-viewpoint pose of the nearby Michelangelo's David, finished nearly 80 years before, this statue is infused with the dynamics that lead towards Baroque, but the tight, uncomfortable, verticality— self-imposed by the author's virtuosic restriction to a composition that could be carved from a single block of marble— lacks the diagonal thrusts that Bernini would achieve forty years later with his Rape of Proserpina and Apollo and Daphne, both at the Galleria Borghese, Rome.

The proposed site for the sculpture, opposite Benvenuto Cellini's statue of Perseus, prompted suggestions that the group should illustrate a theme related to the former work, such as the rape of Andromeda by Phineus. The respective rapes of Proserpina and Helen were also mooted as possible themes. It was eventually decided that the sculpture was to be identified as one of the Sabine virgins.

The work is signed OPVS IOANNIS BOLONII FLANDRI MDLXXXII ("The work of Johannes of Boulogne of Flanders, 1582"). An early preparatory bronze featuring only two figures is in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples. Giambologna then revised the scheme, this time with a third figure, in two wax models now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The artist's full-scale gesso for the finished sculpture, executed in 1582, is on display at the Accademia Gallery in Florence.

Bronze reductions of the sculpture, produced in Giambologna's own studio and imitated by others, were a staple of connoisseurs' collections into the 19th century.

The Loggia della Signoria also houses the Hercules Fighting the Centaur Nessus, commissioned to Giambologna by Grand Duke Ferdinand I around 1594. In Greek mythology, Nessus was a famous centaur who was killed by Heracles, and whose tainted blood in turn killed Heracles. He was the son of Centauros. He fought in the battle with the Lapiths. He became a ferryman on the river Euenos.

Compared to the Rape of the Sabine Women, this group is constructed from a less dynamic stance. The front viewpoint conditions the onlooker; in fact, only from this view is it possible to appreciate the contrast between Hercules' face and the wild, savage face of the centaur, Nessus; the movement of the hero's body is contrasted by the emphatic movement of the monster's trunk, which bends back diagonally. In actual fact, the group was originally designed to be placed on a pedestal at the crossroads in Canto dei Carnesecchi and it was placed under the Loggia in the mid-19th century.

|

|

Giambologna, The Rape of the Sabine Women (detail)

Giambologna, Hercules and Nessus (1599), Florence, Loggia dei Lanzi

|

|

Giambologna, Hercules and Nessus (detail), (1599), Florence, Loggia dei Lanzi

|

Venus of the Grotticella (Fountain of Venus)

|

|

|

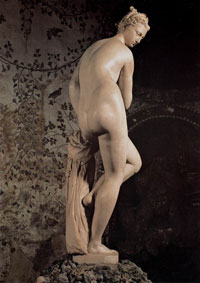

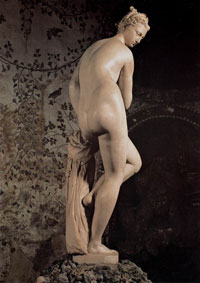

The Venus of the Grotticella is in the part furthest back in the Buontalenti Grotto, built at the wishes of Francesco I.

Against a backdrop of walls covered in mother of pearl, the naked, terse body of Venus (1572-1573) stands out for her twisted torso and shoulders, but above all, for the softness of the finely worked marble, softened by gentle, fluid lines, intended to capture the attention of the onlooker. It is as if a beautiful woman has been turned into a statue or rather, as though the stone above the fountain has become flesh and blood.

Aphrodite bends her head, while her entire silhouette, which is inspired by solutions used by Raphael, seems to continue the curve of her head. The attractive girl rests one foot on the pedestal, which supports an urn for washing and she is about to enter the water beneath a cliff in igneous rock decorated with shells. The border of the basin in multicoloured marble is decorated with four satyrs who, climbing onto the coloured basin, look over it to admire the naked woman.

The satyrs' mouths contain the pipes to spout the parabolic water jets that pruriently and playfully soak the sensual yet diaphanous marble woman. Around the supporting balustrade, there are four curled volutes, decorated with large masks; on the ground are undulations and four heads of Putti, mouths open to provide an outlet for any overflowing water. From a distance, the heads and arms of the satyrs give the overall composition the appearance of a cup with handles, almost an item that would be used for the pomp of an ancient emperor, worshipper of Venus.[5]

|

|

Venus, statue in Buontalenti's Grotto

in the Boboli gardens

|

Giambologna also became extremely famous for his small bronze statues of Venus. The spread of the bronze statue in Florence is largely due to the successful collaboration between Giambologna and his assistant, Antonio Susini, as is the fashion for refined items that were small but which had a strong visual impact: Venus, Hercules, and wild beasts.

Jean de Boulogne also developed a controlled style in the difficult and delicate field of holy art, which fell into line with the new dictats of Catholic Reform.

His religious masterpiece was the Grimaldi Chapel in the now destroyed church of San Francesco di Castelletto in Genoa.

Latter works by Giambologna include the Equestrian Monument to Cosimo I from 1594, a work that changed the whole appearance of Piazza Signoria, giving an unusual dignified air to the city of Florence.[5]

The equestrian statue of Cosimo I de' Medici also in Florence, was completed by his studio assistant Pietro Tacca.

Giambologna provided as well as many sculptures for garden grottos and fountains in the Boboli Gardens of Florence and at Pratolino, and the bronze doors of the cathedral of Pisa. For the grotto of the Villa Medicea of Castello he sculpted a series of studies of individual animals, from life, which may now be viewed at the Bargello. Small bronze reductions of many of his sculptures were prized by connoisseurs at the time and ever since, for Giambologna's reputation has never suffered eclipse.

Giambologna was an important influence on later sculptors through his pupils Adriaen de Vries and Pietro Francavilla who left his atelier for Paris in 1601, as well as Pierre Puget who spread Giambologna's influence throughout Northern Europe, and in Italy on Pietro Tacca, who assumed Giambologna's workshop in Florence, and in Rome on Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Alessandro Algardi.

In 1601, Ferdinando I commissioned an exhausted Jean to make a public monument for the piazza in front of the shrine to the Virgin of the Annunziata.

|

Equestrian statue of Ferdinando I

|

|

Equestrian statue of Ferdinando I de' Medici on the Piazza Santissima

|

The models and designs for this sumptuous bronze statue date back to the period 1600-1602 and the statue itself was finished by Pietro Tacca in October 1608, a short time after the death of Giambologna, aged 79 on 13th August.

The equestrian statue of Ferdinando in armour led to an architectural rearrangement of the extremely popular site and - on the occasion of the marriage between Prince Cosimo and Maria Magdalena of Austria - celebrated the Grand Duke's victory over the Turkish pirates and conquest of the Algerian stronghold of Bona by the Knights of the Order of St Stephen. In fact, the bronze used here comes from the canons of the enemy galleons, as is stated on the girth of the horse: "De' metalli rapiti al fero Trace" [In metals taken from the fierce Thrace].

Compared to Cosimo I in Piazza della Signoria, Giambologna, now an old man, and Tacca decided to give the horse a more elegant style and the rider a controlled countenance, more suited to the spirit of Ferdinando. This can be seen if you read the inscription on the base, with the motto MAIESTATE TANTUM and a queen bee, accompanied by a swarm of other bees in concentric circles, symbolising the peaceful power of the Grand Duke, who had no need to terrorise his subjects, who surrounded him, fully respectful of his royal power. [5]

|

|

Giambologna, Equestrian Monument of Cosimo I, 1587-94, Piazza della Signoria, Florence

|

|

|

| |

|

Most important works

|

|

|

Sansone e un Filisteo (Londra, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1562-67ca.)

Mercurio (Bologna, Museo Civico, 1563);

Fontana del Nettuno (Bologna, Piazza Maggiore, 1563-1566);

Marte (New York, Hall e Knight, 1565-70);

Tacchino (Firenze, Bargello);

Scimmia (Parigi, Louvre, 1570);

Psiche (cosiddetta Betsabea) - (Los Angeles, The J.Paul Getty Museum, 1571-73);

Ratto delle Sabine (Firenze, Loggia dei Lanzi, 1574-80);

Fontana dell'Oceano (Firenze, 1575);

Ninfa dormiente con satiro (Dresda, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, 1575-80);

Nesso d Deianira (Parigi, Louvre, 1576);

Il ratto della Sabina (Napoli, Museo di Capodimonte, 1579);

Giustizia (Genova, Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola, 1579-90);

Mercurio (Firenze, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, 1580);

Mercurio (Parigi, Collection du duc de Brissac, Louvre);

Mercurio (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum);

Colosso dell'Appennino, (Vaglia, località Pratolino, Villa Demidoff, 1580 circa);

Il nano Morgante su un mostro marino (Firenze, Bargello, 1582);

San Filippo (Firenze, San Marco, Cappella Salviati, 1579-1589);

San Giovanni Battista (Firenze, San Marco, Cappella Salviati, 1579-1589);

Statua equestre di Cosimo I de' Medici (Firenze, Piazza della Signoria, 1587-94);

San Giovanni Battista (Firenze, Santa Maria degli Angiolini, 1588);

San Giovanni Battista (Firenze, Santa Maria degli Angiolini, 1588);

Temperanza (Genova, Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola, 1579-90);

Toro (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, 1580-1600);

Tritone (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

San Luca (Museo di Orsanmichele, Firenze, 1597-1602)

Ercole e il Centauro Nesso (Firenze, Loggia dei Lanzi, 1599)

Giambologna in Florence

This visit will take you through Florence, World Heritage Site, following in the footsteps of sculptor Giambologna

|

|

Giambologna in Florence

1. Venere della Grotticella

2. Giove

3. Fontana di Oceano

4. Bacco

5. Palazzo Vecchietti

6. Stemma del duca Cosimo

7. San Luca

8. Ratto delle Sabine

9. Ercole e il Centauro

10. Cosimo I

11. Firenze che vince Pisa

12. Apollo

13. Ercole e l'Idra

14. Monumento equestre a Cosimo I

15. Oceano

16. Bacco

17. Appennino

18. Firenze che vince Pisa

19. Mercurio in volo

20. Architettura

21. Putti pescatori

22. Venere inginocchiata che si asciuga

23. Cappella di Sant'Antonino

24. Ferdinando I a cavallo

25. Cappella mortuaria del Giambologna

26. Casa del Giambologna

|

|

View this map in a larger size |

|

|

|

[1] R. Wellens, Jacques du Broeucq, sculpteur et architecte de la renaissance (Brussels) 1962

[2] Compare the figure of Plato in Raphael's School of Athens.

[3] The marble figure for a Medici fountain, the only large marble group by Giambologna to have left Florence, was given to the Duke of Lerma, then to Charles, Prince of Wales at the time of negotiations for the Spanish Match; it was given by George III to Sir Thomas Worsley, at Hovingham Hall, Norfolk; it was purchased in 1953 for the Victoria and Albert Museum through the Art Fund ([1]; [2]).

[4]A bronze variant is in the Rijksmuseum | www.rijksmuseum.nl

'Heracles (or Hercules in Latin) is the most frequently portrayed hero from antiquity. He is generally shown with a club and a lion’s pelt cloaked over his broad shoulders. Heracles was the son of the supreme god Zeus and his lover Alcmena. Hera, Zeus’ jealous wife, was Heracles’ archenemy. He performed the first of his heroic deeds at the age of eighteen when he killed the lion of Cithaeron. When Hera drove Heracles into a fit of madness causing him to murder his own children, he had to do penance. The Delphic oracle instructed him to serve Eurystheus, king of Argo. Eurystheus gave Heracles twelve impossible labours, including the slaying of various mythological monsters. Assisted by the goddess Athena and his own strength, shrewdness and courage, Heracles proved up to task. After his death he was adopted into the pantheon of the immortal gods.'

[5] Il Giambologna a Firenze | www.giambologna.comune.fi.it

[6] The English word "rape" is a conventional translation of Latin raptio, which in this context means "abduction" rather than its prevalent modern meaning in English language of sexual violation. Recounted by Livy and Plutarch (Parallel Lives II, 15 and 19), it provided a subject for Renaissance and post-Renaissance works of art that combined a suitably inspiring example of the hardihood and courage of ancient Romans with the opportunity to depict multiple figures, including heroically semi-nude figures, in intensely passionate struggle. Comparable themes from Classical Antiquity are the Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs and the theme of Amazonomachy, the battle of Theseus with the Amazons. A comparable opportunity drawn from Christian scripture was the Massacre of the Innocents.

[7] Villa di Pratolino | The villa was built by the solitary Francesco I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany in part to please his Venetian mistress, the celebrated Bianca Capello. The designer of villa and gardens was his court architect- designer- mechanician- engineer Bernardo Buontalenti, who completed it in a single campaign that lasted from 1569 to 1581; it was finished enough to provide the setting for Francesco's public wedding to Bianca Cappello in 1579. In its time it was a splendid example of the Mannerist garden.

Francesco had assembled most of the property, which was not a hereditary Medici possession, by September 1568,[1] and the construction was begun the following spring.

The garden was laid out along a perfectly straight down-slope axis passing through the center of the villa, which stood midway. Down the central descent, the visitor still walks under a cooling arch of fountain jets, without getting wet.

Michel de Montaigne, one of the earliest visitors to leave a description of Pratolino, saw it in 1581,[2] and considered it to have been built, he thought when visiting Villa d'Este, "precisely in rivalry with this place". A long description was published by a Florentine, Francesco de' Vieri, in 1586.[3] Giusto Utens included a view of the southern half of the villa complex among his series of lunettes containing bird's-eye views of the Medicean villas, painted in 1599. Six views were etched by Stefano Della Bella in the mid-17th century, and the picture is rounded out by further 18th century descriptions. Nevertheless, Pratolino has not survived, as other Medici villas have.

Though the villa and its fountains were kept in repair, after Francesco's death it was deserted; in the eighteenth century some of its sculptures were removed to adorn the extension of the Boboli Gardens, and the place was left to fall into decay; by 1798 a German visitor was impressed with the romantic ruin of it.[4] Grand Duke Ferdinand III decided to capitalize on the air of overgrown wildness; in 1820 it was decided to demolish the villa, and the garden was then re-designed in the English landscape manner and became one of the most romantic gardens ever seen in Tuscany. In 1872 the complex was sold by the heirs of Leopold II, former Grand Duke of Tuscany, to Prince Pavel Pavlovich Demidov who restored the Paggeria, or pages' lodgings of the former residence, as the Villa Demidoff di Pratolino. The property was eventually inherited by Prince Paul of Yugoslavia. Later the park was bought by the province of Florence who maintain the park and open it for public use from May until September.

The complicated iconography of the garden is embodied in the brooding statue of "Appennino" (1579-1580), a colossal sculpture by Giambologna, which originally seemed to emerge from the vaulted rockwork niche that once surrounded him. Multiple grottoes with water-driven automata, a water organ, surprise jets that drenched visitors' finery when the fontanieri opened secret spigots, offered striking juxtapositions of Art with imitations of rugged Nature.

Images: www.met.provincia.fi.it

Web: www.provincia.fi.it/pratolino.htm

Bibliography

Gloria Fossi, et al., "Italian Art", Florence, Giunti Gruppo Editoriale, 2000, ISBN 88-09-01771-4.

"Giambologna, 1529-1608 : sculptor to the Medici : an exhibition organised by the Arts Council of Great Britain etc.", catalogue edited by Charles Avery and Anthony Radcliffe.

[London] Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978, ISBN 0-7287-0180-4.

Patrizio Patrizi, Il Giambologna, Milano, L. F. Cogliati, 1905

James Holderbaum, Giambologna, Milano, Fabbri, 1966

Giambologna : Il Mercurio volante e altre opere giovanili, Firenze, Museo Naionzle del Bargello, 1984

Charles Avery, Giambologna : la scultura, Firenze, Cantini, 1987. ISBN 8877370653

Antonio Paolucci, Gli animali del Giambologna, Firenze, Giunti, 2000. ISBN 880901720X

Giambologna tra Firenze e l'Europa : atti del Convegno internazionale, Firenze, Istituto universitario olandese di storia dell'arte, Firenze, Centro Di, 2000. ISBN 88-7038-342-3

Davide Gasparotto, Giambologna, Roma, Gruppo editoriale L'espresso, 2005

Donatella Pegazzano, Giambologna, Firenze, Art e dossier Giunti, 2006

Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi, Dimitrios Zikos (a cura di ), Giambologna : gli dei, gli eroi : Catalogo della

mostra, Firenze, 2006, Firenze, Giunti, 2006. ISBN 8809042921

|

|

Hercules and Nessus, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (Netherlands)

Villa di Pratolino

Appennine Colossus(detail), Giambologna, 1579-1580, Parco Mediceo di Pratolino, Vaglia

|

Il Giambologna a Firenze | www.giambologna.comune.fi.it

Gardens in Tuscany | Il parco di Pratolino e la Villa Demidoff

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles The Rape of the Sabine Women, Villa di Pratolino and Giambologna, published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giambologna.

|

Residency in Tuscany for writers and artists | Podere Santa Pia

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, giardino |

|

Cypress trees between San Quirico d'Orcia and Montalcino |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tombolo di Feniglia |

|

Santa Croce, Firenze |

|

Siena, Duomo |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence |

|

Siena, Palazzo Sansedoni |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Walking in Florence | A Walk Around the Loggia dei Lanzi and the Uffizi Gallery

|

|

|

The Uffizi Gallery contains some of the most important and greatest art collections in the world. It is also the world’s oldest museum.

Built in the shape of a horseshoe extending from Piazza della Signoria to the Arno River and linked by a bridge over the street with Palazzo Vecchio, the Uffizi were intended to house the administrative offices (uffizi) of the Grand Duchy. From the beginning, however, the Medici set aside a few rooms on the third floor to house the finest works of their collections. The Gallery was subsequently enriched by various members of the Medici family. Two centuries later, in 1737, the palace and their collection were left to the city by Anna Maria Luisa, the last Medici heir, and today houses one of the world's great art galleries.

The best way to explore this city is to walk around the thousand little streets that give form to the incomparable and charming historic center. The Uffizi tour leads you through the most important streets, palaces and churches around the Uffizi Gallery. |

|

Michelangelo, L'Importuno

|

| |

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia, with an extraordinary view of the rolling Tuscan hills, up to the seaside and Monte Christo.

One of Tuscany's best kept secrets is the beautiful valley sheltering this recently renovated 18th century farm house,

a villa retaining all the charm and delight of its past combined with updated comfort.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|