|

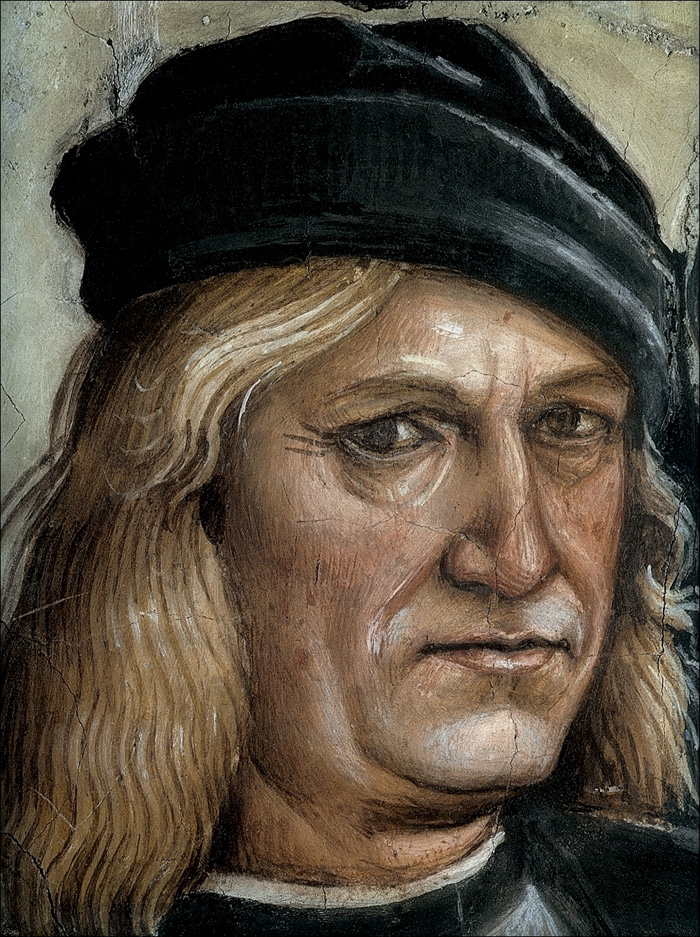

Luca Signorelli, selfportrait,, fresco of the Deeds of the Antichrist (c.1501) in Orvieto Cathedral |

Luca Signorelli (1445 – 1523) |

||

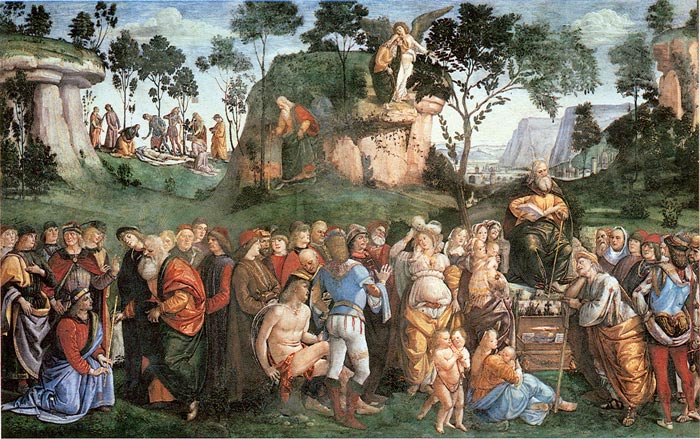

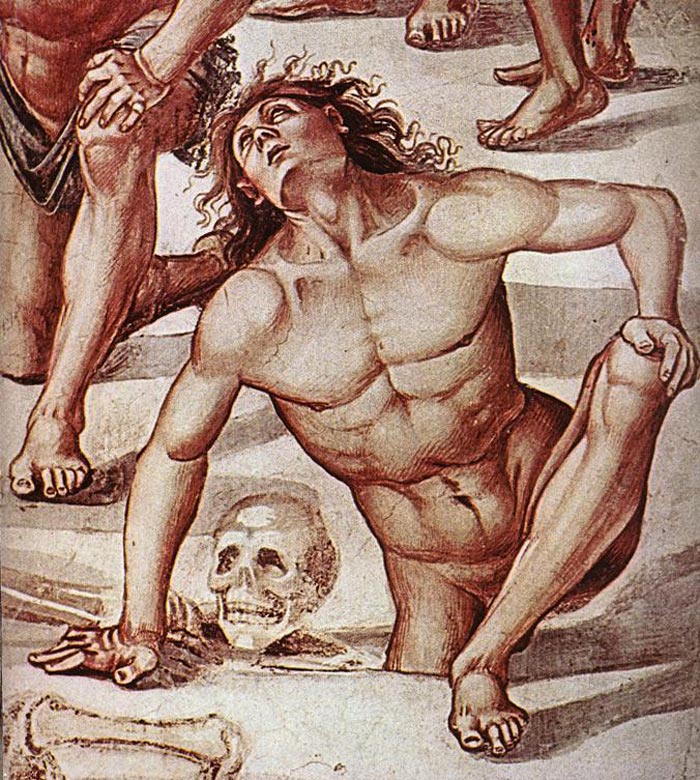

| Luca Signorelli was an Italian Renaissance painter who was noted in particular for his ability as a draughtsman and his use of foreshortening. His massive frescoes of the Last Judgment (1499–1503) in Orvieto Cathedral are considered his masterpiece. Signorelli worked in Rome from 1478–1484. He assisted in the decoration of the lower walls of the Sistine Chapel. The Testament of Moses is almost entirely of his hand. In the latter year he returned to his native Cortona, which remained from this time his home. In the Monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore (Siena) he painted eight frescoes, forming part of a vast series of the life of St. Benedict; they are at present much injured. Luca Signorelli was active in various cities of central Italy, notably Arezzo, Florence, Orvieto, Perugia, and Rome. According to Vasari, Signorelli was a pupil of Piero della Francesca and this seems highly probable on stylistic grounds, for his solid figures and sensitive handling of light echo the work of the master. Signorelli differed from Piero della Francesca, however, in his interest in the representation of action, which put him in line with contemporary Florentine artists. He executed various sacred pictures, showing a study of Botticelli and Lippo Lippi. Pope Sixtus IV commissioned Signorelli to paint some frescoes, now mostly very dim, in the shrine of Loreto — Angels, Doctors of the Church, Evangelists, Apostles, the Incredulity of Thomas and the Conversion of St Paul. He also executed a single fresco in the Sistine Chapel in Rome, the Acts of Moses. Another, Moses and Zipporah, which has been usually ascribed to Signorelli, is now recognized as the work of Perugino. The wall paintings of the Sistine Chapel are among the most important examples of the type of painting developed in Florence in the later fifteenth century. The five artists brought to Rome to execute them were Botticelli, Ghirlandaio and Rosselli from Florence, Perugino from Umbria and Luca Signorelli from Cortona. Signorelli worked in Rome from 1478–1484. He assisted in the decoration of the lower walls of the Sistine Chapel. The Testament of Moses is almost entirely of his hand. In the latter year he returned to his native Cortona, which remained from this time his home. In the Monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore (Siena) he painted eight frescoes, forming part of a vast series of the life of St. Benedict. The two last frescoes of the Monte Oliveto series indicate that an immense force lay in reserve, waiting an opportunity for some wider and freer field of action, than had hitherto presented itself. That opportunity now came, when, at the age of fifty-nine, he was called upon to undertake the vast work of these Orvieto frescoes. From the Monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, Signorelli went to Orvieto, where he painted a magnificent series of six frescoes illustrating the end of the world and the Last Judgement (1499-1504), in the chapel of S. Brizio (then called the Cappella Nuova), in the cathedral. The Cappella Nuova already contained images in the vaulting over the altar by Fra Angelico, who had begun the murals fifty years earlier. The works of Signorelli in the vaults and on the upper walls represent the events surrounding the Apocalypse and the Last Judgment. The work is entirely the product of Signorelli's powerful imagination, though, of course, he was influenced by literary sources - Gospels, Apocryphal Gospels, Golden Legend, and Dante's Divine Comedy.The events of the Apocalypse fill the space which surrounds the entrance into the large chapel. In the grand and dramatic scenes in Orvieto, inspired by the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, he displayed a mastery of the nude in a wide variety of poses surpassed at that time only by Michelangelo. Perhaps the most interesting is the enigmatic seated nude youth in Signorelli's Last Acts and Death of Moses in the Sistine Chapel, which is remarkably close to some of the Ignudi painted by Michelangelo on the ceiling of the chapel a quarter of a century later. By the end of his career, however, Luca had become a conservative artist, working in provincial Cortona, where his large workshop produced numerous altarpieces. In 1520 Signorelli went with one of his pictures to Arezzo. He was partially paralysed when he began a fresco of the Baptism of Christ in the chapel of Cardinal Passerini's palace near Cortona, which (or else a Coronation of the Virgin at Foiano) is the last picture of his specified. |

The portraits, as identified by the inscription at the bottom, are Luca Signorelli, who painted the frescoes in the San Brizio Chapel between 1499 and 1504, and the chamberlain Niccolò d'Agnolo, in office during that time.[3]

|

|

| Cortona |

||

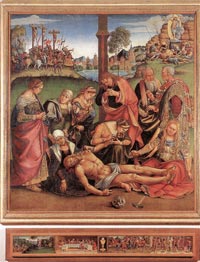

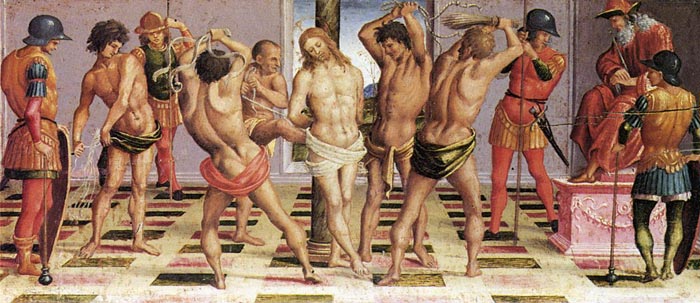

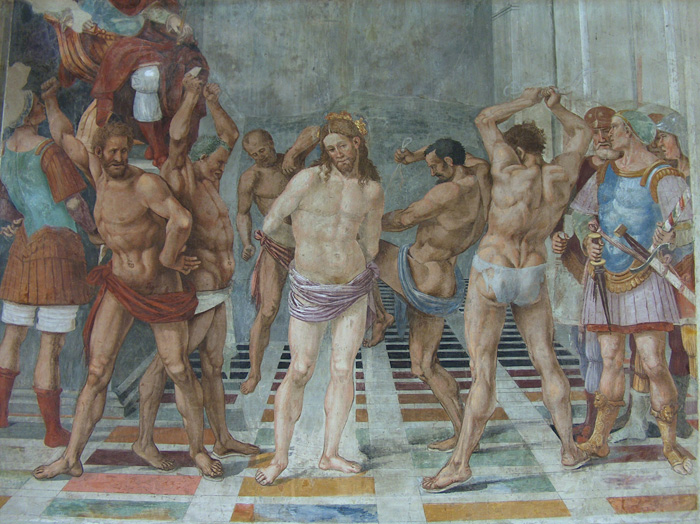

| The predella of the altarpiece depicts me Agony in the Garden, the Last Supper, the Arrest of Christ, and the Flagellation. The central group of the Virgin Mary, the dead Christ and a holy woman who kisses his hand have been correctly related to the very similar group at Orvieto (Fig. 58/20 on p. 204). It is now certain that these figures derive from me same cartoon and were used first in Cortona, and subsequently at Orvieto. The fame of this altarpiece, which Vasari described in 1550 as held to be a beautiful thing and worthy of great praise, resulted in various other variants. In 1505 Signorelli was commissioned to paint the high altarpiece for the church of Sant'Agostino at Matélica (Cats. 65-9) "just as he has painted and perfected the high altarpiece of the church of Santa Margherita in Cortona". The fresco at Castiglion Fiorentino (Cat. 72) also derives from the Cortona Lamentation. "The expressive pathos of the picture has sometimes been related to Vasari's tragic description of how Signorelli stripped and drew me lifeless body of his son without shedding a tear. Some commentators have gone further and suggested that the figure of Christ in this picture was based on this posthumous study. While there may be a grain of truth in Vasari's anecdote (which Vasari introduced as local hearsay), mere are problems with connecting it to the Cortona Lamentation. Signorelli's son Antonio was alive in February 1502, when mis picture was completed, but he died-almost certainly of the plague-in the summer of 1502. One possibility is that Antonio was me model for me figure of Christ in this painting, and mat Vasari's pathetic anecdote was an accretion that followed Antonio Signorelli's death and me contemporary "unveiling" of Signorelli's altarpiece. [1] This work seems to be straining to escape from the cruel and tragic style of the Last Judgment of Orvieto and the Lamentation of Cortona, in order to imitate the sweet tones of the airy architecture of Raphael and the new sixteenth-century school. The iconography of this panel is very unusual. The apostles, some standing, some on their knees, surround Christ to receive the consecrated Host. This contrasts with the traditional way in which the apostles are represented, seated around a set table. A classical structure functions as a background. The work reminds one of the rhythmic works of Perugino and seems to imitate Raphael's School of Athens. The figure of Judas is stupendous; he is leaning to one side hiding the Host in his bag with a look that shows the painful realization of his betrayal. | ||

|

||

Luca Signorelli, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, scene from the predella The Flagellation, 1502, Museo Diocesano, Cortona |

||

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ in its original arrangement, mounted in an antique frame with pillars in which were represented seven saints, once enriched the scenography of the high altar of the ancient church of St Margaret in Cortona. This was surely admired by Pope Leo X when, during a stop on his way to Bologna to meet Francis I of France, he visited the church in 1515. In the second half of the 1700s the painting was moved, deprived of its frame, and finally placed in the choir of the cathedral of its origin. "The expressive pathos of the picture has sometimes been related to Vasari's tragic description of how Signorelli stripped and drew me lifeless body of his son without shedding a tear. Some commentators have gone further and suggested that the figure of Christ in this picture was based on this posthumous study. While there may be a grain of truth in Vasari's anecdote (which Vasari introduced as local hearsay), mere are problems with connecting it to the Cortona Lamentation. Signorelli's son Antonio was alive in February 1502, when mis picture was completed, but he died-almost certainly of the plague-in the summer of 1502. One possibility is that Antonio was me model for me figure of Christ in this painting, and mat Vasari's pathetic anecdote was an accretion that followed Antonio Signorelli's death and me contemporary unveiling of Signorelli's altarpiece. [1]The Lamentation, a work done entirely the artist alone, reveals all the poetry of the painter even in the context of an unrefined style which may seem declamatory, scenic and rhetorical. In the predella that Signorelli probably painted with the help of his assistant, Gerolamo Genga, four scenes from the Passion of Christ are represented: The Prayer in the Garden, The Last Supper, The Capture and The Flagella tion. |

||

| Luca Signorelli’s Communion of the Apostles depicts the moment in which Christ administers his body and blood to the Apostles. The iconography of this panel is very unusual. The apostles, some standing, some on their knees, surround Christ to receive the consecrated Host. This contrasts with the traditional way in which the apostles are represented, seated around a set table. A classical structure functions as a background. The work reminds one of the rhythmic works of Perugino and seems to imitate Raphael's School of Athens. The figure of Judas is stupendous; he is leaning to one side hiding the Host in his bag with a look that shows the painful realization of his betrayal. |

||

A further work by Signorelli can be found in the unassuming Chiesa di San Nicolo. Climbing from Piazza della Repubblica on Via Santucci and then Via Berrettini brings you into the upper town. Beyond a cypress-lined courtyard, is the 15th century Chiesa di San Nicolò. The unassuming 15th-century church has a small porch with slender columns. Ring the bell on the left-hand side wall, and the caretaker will take you to Signorelli's double-sided altarpiece, revealed by a neat hydraulic system that swivels the picture away from the wall. |

Compianto sul Cristo morto tra angeli e santi (1516 circa), Cortona, chiesa di San Niccolò |

|

The Renaissance palace Palazzo Passerini (called Il Palazzone) is located outside the massive ancient town walls of Cortona. The interior is composed of a spacious, arcaded courtyard with a central well. Opposite the courtyard from the entrance there is the Chapel, with Luca Signorelli's Baptism of Christ, in unfortunately bad condition. Vasari wrote of this painting that Signorelli “was not able to finish it because he died while he was working on it”.

|

||

| Orvieto |

||

|

||

Luca Signorelli, Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto |

||

|

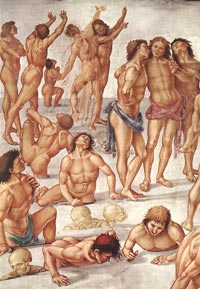

The decoration of the San Brizio chapel in the Orvieto Cathedral.started in 1447 by Fra Angelico and Benozzo Gozzoli, who executed two compositions (Christ the Judge and Prophets) on the vaults. [1] The commission was only revived at the end of the century. The painter Luca Signorelli was chosen thanks to his fame as a fast executor. In only three years, from 1499 to 1502, the decoration was planned and executed, with a speed and efficiency that is practically unique in the history of Italian art. His massive frescoes of the Last Judgment (1499–1503) in Orvieto Cathedral are considered his masterpiece. In the grand and dramatic scenes, inspired by the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, Luca Signorelli displayed a mastery of the nude in a wide variety of poses surpassed at that time only by Michelangelo. As far as the subject matter is concerned, it is one of the most important subjects of Christian iconography. It is likely that for the ceiling frescoes (the groups of Apostles, Angels, Patriarchs, Doctors of the Church, Martyrs and Virgins) Signorelli simply completed the programme that had originally been devised by Fra Angelico. But the frescoes on the side walls, although the basic subject would have been planned in accordance with the Cathedral's administrators and theologians, are wholly the product of Signorelli's fertile imagination. The side walls are covered with seven large scenes: the Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist, the Destruction of the World, the Resurrection of the Flesh, the Damned, the Elect, the Paradise and the Hell. The lower part of the walls is decorated with grotesque patterns and with busts of philosophers and poets alongside monochromes commenting their works, as well as illustrations from the Divine Comedy. Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist is the masterpiece of the whole cycle (at least in terms of originality of invention and evocation of fantastic imagery) even Signorelli himself must have realized, and he has placed himself, together with a monk (traditionally identified as Fra Angelico) on the lefthand side of the composition. The account of the Apocalypse then continues with three large scenes, the Resurrection of the Flesh, the Damned and the Elect, and two smaller ones on either side of the chapel's window, Paradise and Hell. It is primarily in this section of the fresco cycle that Signorelli has given free rein to his inventive genius. An inventiveness that, as Berenson said, made him one of the greatest of modern illustrators, and thanks to which his art is still an extremely important part of our figurative heritage. Despite the rhetorical devices, the theatrical ruses and the occasional contrived details, despite the limitations in his draughtsmanship and use of colour recognized by all modern critics, there is no denying that never before in Italian art had figurative ideas of such unforgettable power been used. Viewed all together the huge frescoes in the Orvieto chapel give an impression of overcrowding and of confusion which is far from pleasing. We have to isolate the individual details in order to grasp the greatness of Signorelli the 'illustrator' and the 'inventor' and therefore justify Berenson's statement. See, for example, in the Resurrection of the Flesh, the macabre but hilarious idea of the nude with his back to the observer who is carrying on a conversation with the skeletons; or the skulls surfacing through the cracks in the ground, who put on their bodies as though they were a costume, and become human beings once again. |

||

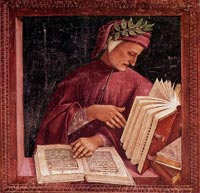

The lower parts of the walls are executed as decorative panels. In the center of each panel is a portrait of a poet or a philosopher – Dante, Virgil, Ovid, Horace, Lucian, Homer and Empedocles. Each portrait is surrounded by four tondos with the scenes from their works. In his most celebrated work the Divine Comedy, Dante narrates a journey through Hell and Purgatory, guided by Virgil, and finally to Paradise, guided by Beatrice. The Divine Comedy gives an encyclopedic view of the highest culture and knowledge of the age all expressed in the most exquisite poetry. It was highly appreciated both by his contemporaries and following generations. Many artists took the subjects from the Divine Comedy for their paintings. |

||

| Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore | Asciano |

||

|

||

Luca Signorelli, Come Benedetto dice alli monaci dove e quando avevano mangiato fuori dal monastero (dettaglio), Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore |

||

| In Chiusura, five miles south of Asciano, in the province of Siena, the Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, an imposing monastic compound featuring the famous cycle of frescoes Le storie di Benedetto by Luca Signorelli and Antonio Bazzi, called Il Sodoma, an ingenious artist from Piedmont who lived at the turn of the 16th century. The abbey was founded in 1319 by three Senese noblemen, Bernardo Giovanni Tolomei, Patrizio Patrizi and Ambrogio Piccolomini, who decided to give up their wealth and privileges in favour of living according to the rule of St Benedict. The abbey boasts three 15th century cloisters, of which the most magnificent is the rectangular Chiostro Grande, constructed between 1426 and 1443. It is made up of two walkways one above the other, supported by columns. The portico is decorated with a fresco cycle depicting the life of St Benedict by Luca Signorelli, who began work on its 36 large scenes in 1497. The cycle was finished in 1508 by Sodoma. The Chiostro Centrale is composed of a portico that rests on polygonal columns that lead to the magnificent Refectory, decorated with frescoes by Fra’ Paolo Novelli. From the Monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore near Siena, Signorelli went to Orvieto, and produced his masterpiece, the frescoes in the chapel of S. Brizio (then called the Cappella Nuova), in the cathedral. | ||

The year following the execution of these frescoes Signorelli was in Siena, painting the two wings for the altar-piece of the Bicchi family, formerly in the Chiesa di Sant’Agostino, now in the Staatliche Museen Berlin. Vasari writes of it : "At Siena he painted in Sant' Agostino, a picture for the chapel of S. Cristofano, in which are some Saints surrounding a S. Christopher in relief."

|

||

|

|

||

Rome |

||

|

||

Luca Signorelli and Bartolomeo della Gatta, Testament and Death of Moses, oil on panel, 21.6 x 48 cm, Vatican City, Sistine Chapel, Rome |

||

| Together with his Florentine colleagues Domenico Ghirlandaio and Cosimo Rosselli and the Perugian Pietro del Perugino, Botticelli was to decorate the walls of the papal electoral chapel - called the "Sistine Chapel" after its builder, Sixtus IV - with frescoes. Botticelli painted three scenes within the short period of eleven months: Scenes from the Life of Moses, The Temptation of Christ and The Punishment of Korah. However, it was not until the later work on it by Michelangelo, who executed the frescoes on the ceiling and the altar wall between 1508 and 1512 under Julius II, that the chapel would achieve its greatest fame. The Punishment of Korah and the Stoning of Moses and Aaron is from the cycle of the life of Moses in the Sistine Chapel. It is located in the fifth compartment on the south wall. The message of this painting provides the key to an understanding of the Sistine Chapel as a whole before Michelangelo's work. The fresco, located in the fifth compartment on the south wall, reproduces three episodes, each of which depicts a rebellion by the Hebrews against God's appointed leaders, Moses and Aaron, along with the ensuing divine punishment of the agitators. Signorelli worked in Rome from 1478–1484. He assisted in the decoration of the lower walls of the Sistine Chapel. The Testament of Moses is almost entirely of his hand. Signorelli must have had a considerable reputation by about 1483, when he was called on to complete the cycle of frescoes on the walls of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, left unfinished by Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Perugino, and Rosselli. It's is not known why these four artists abandoned the work in 1482, but it has been suggested that they simply downed tools because of slow payment. Signorelli completed the scheme with distinction. [read more] |

||

Città di Castello, San Crescentino Oratory, Oratorio di San Crescentino |

||

|

||

| The Oratorio di San Crescentino is located in Morra, a locality a few kilometers from Città di Castello. Built in 1420 and enlarged in 1507, the Oratory was dedicated to the Roman soldier Crescentinus, a witness of the Christian faith in the High Tiber Valley and martyrized in 303 A.D. by order of the Emperor Diocletian. The inside of the Oratory has a single nave that preserves late Gothic frescoes related to the original structure in the sacristy and, along the walls, a decoration executed by the workshop of the painter from Cortona, Luca Signorelli. The scenes of the Flagellation and the Crucifixion are the only ones made by Signorelli. |

|

|

| In 1498 Luca Signorelli executed a great altarpiece for the Bichi Chapel in the church of Sant'Agostino, Siena. Two wings, now in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin, flanked a statue of St Christopher ascribed to Francesco di Giorgio Martini (Musée du Louvre, Paris). The predella is now divided between various museums.

The left wing of the altarpiece represents Sts Catherine of Siena, Magdalen, and the kneeling St Jerome. |

|

|

The right wing of the altarpiece represents Sts Augustine, Catherine of Alexandria and the kneeling Anthony of Padua.

|

||

The Crucifixion Standard (lo Stendardo della Crocifissione) is a double-sided c.1502-1505 tempera on panel painting by Luca Signorelli, produced late in his career and now on the high altar of Sant'Antonio Abate church in Sansepolcro.

|

Luca Signorelli, Crucifixion Standard (Anthony the Great and John the Evangelist), Chiesa di Sant'Antonio abate (Sansepolcro) | |

|

||

| Luca Signorelli, Resurrection of the Flesh(detail), 1499-1502, fresco, Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto |

||

|

|

||

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Siena, Piazza del Campo |

Orbetello | ||

|

||||

Bagni San Filippo |

Montalcino |

Siena, Duomo |

||

|

||||

| The Villa offers its guests a breathtaking view over the Maremma hills. On clear days or evening, one can even see Corsica. | ||||