|

|

Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore |

|

The Master of Monte Oliveto |

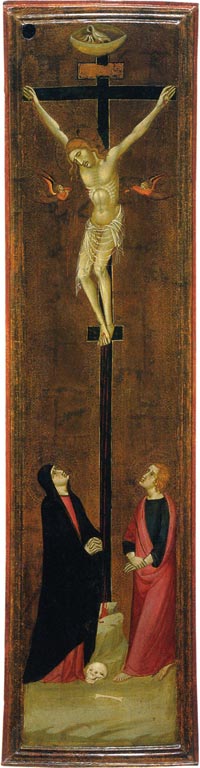

| The Monte Oliveto Master, a highly distinctive artist who worked in the close following of Duccio but who probably did not train in his workshop who takes his name from a panel of The Enthroned Madonna in the monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, in Asciano, near Siena. The Asciano panel almost certainly derives from Duccio's lost Maesta of 1302, which was painted for the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, and must have been executed within a few years of Duccio's original. |

||

The story of Sienese painting in the wake of its brilliant founder, Duccio di Buoninsegna (active ca. 1278–d. 1318), is a complicated one. As Duccio's fame spread and his innovations in style, composition, and painterly technique became more widely known to his contemporaries, a flurry of artists rushed to capitalize on the new developments. For years scholars have struggled to determine which artists actually studied in Duccio's workshop and which ones were more geographically and temporally removed imitators. The Master of Monte Oliveto, an anonymous Ducciesque painter named for a picture he made for the monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, near Asciano (Tabernacle Center with the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Angels and Annunciation), has been one such subject of divided opinion. The Master of Monte Oliveto has traditionally been thought of as a close follower of Duccio, and several scholars have suggested that he actually worked for some time in the shop of the great master, placing his years of activity from about 1300 to about 1320. However, most of these observations rely heavily on iconographical comparisons between the Master's and Duccio's works. This method of scholarship is an imperfect one to use as a basis for dating for two reasons. First, scholars simply cannot know what pictures have been destroyed that might provide even more accurate comparisons. Second, this method does not take into account the time and distance iconographical and stylistic developments might have taken to travel to more provincial artists. Scholars who keep these two things in mind are more aptly prepared to disentangle many of the complicated issues surrounding Sienese painting in the early to mid-fourteenth century. Such is the case with the Master of Monte Oliveto, who worked primarily on small objects for personal devotion, such as tabernacles and triptychs (18.117.1) (no large altarpieces are known to have been painted by him). The Master's style is often recognizable by the heavy white highlights he uses to indicate lips, noses, and other facial features. His body of work reveals an artist who probably catered to a largely provincial clientele, which was perhaps less rigorous in its demands for the most up-to-date painterly trends. By attempting to understand his oeuvre this way instead of forcing him into the ranks of Duccio's closest followers, it becomes much easier to understand the chronological arrangement of the Master's paintings. Looked at this way, the Master of Monte Oliveto's work is far closer to that of one of Duccio's earliest and most well-known pupils, Segna di Buonaventura. Two of the earliest works by the Master of Monte Oliveto are a diptych at the Yale University Art Gallery and a pair of tabernacle wings at the Metropolitan (41.190.31a–c). Several details indicate that these pictures should be placed in the early part of the Master's career. First, along with his eponymous work, these paintings are the only ones in which a simple stylus tool was used to create patterns in the gilding. Punch tools were only popularized in Siena after the second decade of the fourteenth century, during the end of which Simone Martini used them extensively throughout his famous Maestá for the Palazzo Pubblico. After this monumental work, punch tools practically became the rule for the ever-decorative Sienese artists, though they were rarely, if ever, used before. Even more telling in terms of dating are the figural groups in the Crucifixion scene of the Yale diptych, which, though loosely copied from Duccio's Maestá (1308–11), betray an obvious lack of spatial conception. Later on in his career, the Monte Oliveto Master learned to correct this problem, and painted quite convincing figural groups in the wings of another of his tabernacles, also in the Metropolitan's collection (18.117.1). The early tabernacle wings at the Metropolitan (41.190.31a–c) are a good example of why it can be so difficult to understand the chronology of a painter's oeuvre from iconographical comparisons—it is clear that here the Master of Monte Oliveto has mixed and matched elements from his compositional repertoire. While all four narrative scenes share their compositional format almost identically with the comparable scenes from Duccio's Maestá (finished ca. 1311), the artist has not given up on older prototypes, reverting to the archaic niche-throne type developed by Jacopo Torriti around 1290 for the scene of the Annunciation. This mixing of old and new prototypes continues later on in the Master's career. One of the artist's more mature tabernacle centers, in the Alana Collection, uses the more antiquated technique of chrysogony (the patterning of gold lines on painted robes). In the scene of Christ Mounting the Cross, a rare subject in Trecento painting, the iconographic model is taken from Guido da Siena's San Domenico altarpiece of 1280. However, the artist has also employed the more modern technique of punch tooling and has included a trefoil arch at the top of the panel, a style that became popular in Siena only after Simone Martini's polyptych for the city's convent of Santa Caterina in 1319. It is clear that, when studying artists like the Master of Monte Oliveto, scholars must be wary of using composition and iconography as a fail-safe method for dating. Some of the Master's habits described here may cause viewers to think of him as little more than a copycat artist. However, this is far from the truth. The Master of Monte Oliveto's works are lively, tender, and innovative in their details. On close examination, viewers will instantly recognize how evocative and emotional his pictures can be even when they have been copied from earlier prototypes. Overall, the pictures reveal an artist with a refined sensibility who, though not an innovative genius, was certainly a gifted member of the Sienese school. |

|

|

J.H. Stubblebine, op. cit., vol. 1, pp. 93- 94, vol. it, plates 210, 211 As J.H. Stubblebine observes, '...It is his early paintings... that are the most characteristic and successful. In these he is distinctively somber in color, with dark flashes of orange amidst browns, purples, and blacks; here too, the stiff figures with their guarded glances convey most intensely the poetic mood that is one of the Monte Oliveto Master's most enduring qualities....' |

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Siena, Piazza del Campo |

Bagni San Filippo |

||

|

|

|||

| The towers of San Gimignano | Montalcino |

Siena, Duomo |

||

| Cortona, Santa Maria de Nuova | Orvieto, Duomo |

Abbazia di Monte Oliveta Maggiore | ||

|

||||

| The Villa offers its guests a breathtaking view over the Maremma hills. On clear days or evening, one can even see Corsica. | ||||