|

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Adoration of the Magi (detail, self Portrait), 1488, Spedale degli Innocenti, Firenze [1]

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449 – 1494) was one of the most popular Florentine artists of his time. His father, Tommaso di Curradi Bigordi, had a business with jewellery, and Domenico started as a goldsmith. His nickname of Ghirlandaio, the Garland-maker, came from his speciality, the manufacture of silver or gold crowns or diadems, popular with young women of Florence. |

||

Ghirlandaio's full name is given as Domenico di Tommaso di Currado di Doffo Bigordi. The occupation of his father Tommaso Bigordi and his uncle Antonio in 1451 was given as "'setaiuolo a minuto,' that is, dealers of silks and related objects in small quantities." He was the eldest of six children born to Tommaso Bigordi by his first wife Mona Antonia; of these, only Domenico and his brothers and collaborators Davide and Benedetto survived childhood. Tommaso had two more children by his second wife, also named Antonia, whom he married in 1464. Domenico's half-sister Alessandra (b. 1475) married the painter Bastiano Mainardi in 1494.[1] First works in Florence, Rome and Tuscany Later works in Tuscany |

||

|

||

Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple, fresco in the Cappella Tornabuoni, Santa Maria Novella, Firenze |

||

Other distinguished works from Ghirlandaio's hand are an altarpiece in tempera of the Virgin Adored by Saints Zenobius, Justus and Others, painted for the church of Saint Justus, and considered a remarkable masterpiece—in modern times it has been in the Uffizi gallery. Christ in Glory with Romuald and Other Saints, in the Badia of Volterra; what may be considered his finest panel-picture, the Adoration of the Magi (1488), in the previously-mentioned Church of the Innocenti, and the Visitation (Louvre) which bears the last ascertained date (1491) of all his works. Ghirlandaio did not often attempt the nude—one of his pictures including nudes, Vulcan and His Assistants Forging Thunderbolts, was painted for Lorenzo II de' Medici, but, as in the case of several others specified by Vasari, no longer exists. The mosaics that he produced date before 1491—one, of special note, is the Annunciation, on a portal of the cathedral of Florence. Critical assessment and legacy |

||

First works in Florence, Rome and Tuscany

|

||

|

||

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, about 1472, fresco, Ognissanti, Florence , |

||

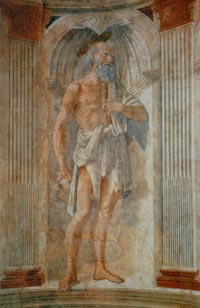

The first known work by Domenico Ghirlandaio is the apse fresco in the parish church of Sant'Andrea at Cercina. Sant' Andrea is a primitive old church, reached by a double flight of steps; and adjoining it was the first convent for nuns in Florence. Saints Jerome, Barbara and Anthony Abbot are portrayed within a false architecture with niches divided by fluted pilaster strips and Corinthian capitals. |

||

The village church of Cercina, near Florence, has a fresco of three saints, now thought to be Ghirlandaio's earliest work, but there is general agreement that some frescoes in the church of Ognissanti in Florence, almost certainly dating from around 1472-73, show his style at its earliest developed stage. One of them represents the Pietà and depicts several members of the Vespucci family as mourners, thus already introducing Ghirlandaio's characteristic combination of portrait figures in contemporary dress with a specifically religious subject. |

|

|

The Stories of Santa Fina at San Gimignano (1473-75) |

||

|

||

Ghirlandaio, Obsequies of St Fina, 1473-75, fresco, Collegiata, San Gimignano |

||

| Violets flower in March in San Gimignano, a town of many towers; they are celebrated as the "Fiori di Santa Fina", the flowers of Saint Fina, the town's patron saint. Fina, the pious daughter of poor parents, died on the feast day of Saint Gregory in 1253 after a long and painful illness. She was just fifteen years old. According to legend, after the death of her mother Fina lived an ascetic lifestyle so strict she was, in the end, scarcely able to move. At the instant she died, white, beautifully scented flowers blossomed forth from her bed of pain. Entering the central nave we find two famous wooden statues by Jacopo della Quercia standing on both sides of the fresco illustrating the Martyrdom of St. Sebastiano by Benozzo Gozzoli. On the upper part of the central nave between the two doors, above the first two arches on the right and left hand sides are Taddeo di Bartolo’s frescoes showing The Last Judgement. In the right aisle, next to the transept, we find the famous Chapel of Santa Fina built in 1468. It is the most precious work of art in the Duomo thanks to its elegant altar by Benedetto da Maiano and to its frescoes by Domenico Ghirlandaio representing on the right hand side St. Gregorio foretelling St. Fina of her approaching death and on the left hand side Her Funeral Rites. Between 1468 and 1472, architect Giuliano da Maiano built Saint Fina's mortuary chapel in the collegiate church (his brother Benedetto da Maiano created the saint's burial altar about 1475) and Ghirlandaio covered the walls with frescoes. Both artists were working in direct competition with each other, for they were depicting the Obsequies of Saint Fina side by side, each using his own medium, fresco and relief carving. The entire layout of the magnificent ensemble, which is still in its original location, is reminiscent of Antonio Rossellino's mortuary chapel for the Portuguese cardinal dating from 1461-66 in the Florentine church of San Miniato al Monte, the frescoes for which were painted by Ghirlandaio's first teacher, Alessio Baldovinetti. It was in the frescoes for this chapel Ghirlandaio was able to develop his own style. The two frescoes in the Saint Fina Chapel are the first major works of Ghirlandaio's career. There are already signs of the architecture that will feature in his later works, here imaginatively and skillfully constructed according to the laws of perspective. The spaces appear to be filled with light and air and to create a bright atmosphere that is enhanced by the luminous colours of Domenico Veneziano. Also evident here is Ghirlandaio's ability, which was much appreciated by his patrons, of including them and their families in religious scenes. The year in which the frescoes in the chapel of St Fina were executed can be fixed almost with certainty at 1475 or shortly after. There are two Stories of St Fina: the Apparition to Fina of St Gregory who announces her Death and the Obsequies of the Saint. In the long row of expressive heads Ghirlandaio already reveals his unique ability to create convincing character studies, a skill that was to bring him fame and many well paid commissions. Some of those depicted do not seem to be taking part in the ceremony, while others are deeply moved. The server at the saint's feet is more interested in his processional cross than in the ceremony, and the server next to him is looking around to keep himself amused. In the lower left corner on of the miracles can be seen: a blind choirboy who kisses her foot regains his sight. Art in Tuscany | Domenico Ghirlandaio | The Santa Fina Chapel in San Gimignano, Chiesa Collegiata |

|

|

Calling of the Apostles, 1481, fresco in the Cappella Sistina |

||

|

||

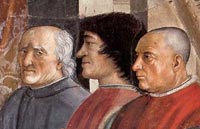

| In 1481–82 Ghirlandaio received an important commission in the Vatican for a fresco, representing the calling of Peter and Andrew to their Apostleship. Although he is known to have created other works in Rome, they have been for centuries considered lost to history. He also produced frescoes, dated before 1485, for Cappella di Santa Fina, in the Tuscan Collegiata di San Gimignano which came under the rule of nearby Siena at the beginning of the 1350s. The frescoe is especially successful in its sense of openness and is one of the clearest and most easily read in the chapel. Characteristically, the "calling" is witnessed by crowds of onlookers and contains numerous contemporary portraits. The group of characters on the right are all, or almost all, real portraits. Represented here are the most important components of the large Florentine colony in Rome - figures belonging to the most illustrious families of the city who had opened branches of their Florentine businesses in Rome, but above all the representatives of the Medici House banks of credit and commerce. Giovanni Tornabuoni (whose sister was the wife of Piero de' Medici) figures prominently among the other characters portrayed. Head of the Medici Bank in Rome, he was so expert in financial and business affairs that he becvame the treasurer of Sixtus IV. Tornabuoni now is elderly, or so it wold appear from his austere countenance and the deep wrinkles that furrow his brow and temples. Lorenzo, still almost a boy, stands in front of his father, his sad face revealing a certain feminine softness. Futher along the line, in profile, possibly another Tornabuoni is portrayed, the noble and cultivated Cecco. The character on the far right of the group is a member of the Vespucci family, Giovanni Antonio, whose sharp profile is illumined by a bright light that seems almost to lend him the suggestion of a smile. Another bare-headed gentleman, with white hair and a pensive expression is thought by some to be the Florentine Francesco Soderini. Argyropulus is also among the Florentines, the old man with the resentful expression and rather weak face framed by a short white beard, and with his head covered by a strange, hard, almost prelatic hat. The Greek John Argyropulus, born in Constantinople but driven out by the Turks in 1453, had found refuge in Florence, in the cultivated circle of the Medici, whose guest he was for fifteen years. He had held the professorship of Greek at the university of Florence and Lorenzo il Magnifico had made him a citizen of Florence, which had become the city of his choice. When Argyropulus was called to Rome by Sixtus IV, he continued to regard himself as a Florentine and as such, with the others, Ghirlandaio portrayed him. Art in Tuscany | Domenico Ghirlandaio, Calling of the Apostles, 1481, fresco in the Cappella Sistina |

||

The Sassetti Chapel frescoes (1486) in Sta Trinita, Florence, are among Ghirlandaio's best work. The episodes, of the life of St. Francis, are embellished by contemporary Florentine settings and personalities. In the lunette scene depicting Francis receiving the rules of the order, the setting is the Piazza della Signoria with a view of the Loggia dei Lanzi. Among those witnessing the event are Lorenzo the Magnificent, Francesco Sassetti (the donor), and the writer Angelo Poliziano. The scene showing Francis resuscitating a child is set in the Piazza Sta Trinita with views of the bridge and Church of Sta Trinita. |

||

|

||

Back in Florence in 1485, Ghirlandaio painted fresco cycles in the Sassetti chapel of Santa Trinita for the donor and banker Francesco Sassetti, the powerful manager of the branch of the Medici bank in Genoa, a position subsequently filled by Giovanni Tornabuoni — Ghirlandaio's future patron. In the chapel, Ghirlandaio painted six scenes from the life of Saint Francis, including Saint Francis obtaining from Pope Honorius the Approval of the Rules of His Order, Death and Obsequies and Resuscitation, by the interposition of the beatified saint, a child of the Spini family, who died as a result of a fall from a window. The first work depicts a portrait of Lorenzo de Medici, and the third, the painter's own likeness, which he also included in one of his pictures in the Santa Maria Novella as well as in the Adoration of the Magi in the Ospedale degli Innocenti orphanage. The altarpiece from the Sassetti chapel, the Adoration of the Shepherds, is now in the Florentine Academy.

|

||

Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Adoration of the Shepherds, , 1483-85, panel, 167 x 167 cm, Santa Trinità, Firenze

|

||

The Santa Trinita church in Florence has several interesting works of art, but the piece de resistance is without doubt one of the finest and most complete remaining Renaissance chapels - Ghirlandaio's Capella Sassetti. The Sassetti Chapel was frescoed between 1482 and 1485 by Domenico Ghirlandaio. The fresco Confirmation of the Rule depicts Angelo Poliziano, with his students, the sons of Lorenzo de' Medici who can be seen on the right.

|

|

|

The Cappella Tornabuoni |

||

| The Tornabuoni Chapel is the main chapel (or chancel) in the church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy. It is famous for the extensive and well-preserved fresco cycle on its walls, one of the most complete in the city, which was created by Domenico Ghirlandaio and his workshop between 1485 and 1490. |

||

Immediately after the commission for the Sassetti chapel of Santa Trinita, Ghirlandaio was asked to renew the frescoes in the choir of Santa Maria Novella, which formed the chapel of the Ricci family, but the Tornabuoni and Tornaquinci families, which were much more prominent than the Ricci, undertook the cost of the restoration, with conditions—the question of preserving the arms of the Ricci gave rise to what some historians described as amusing litigation. The Tornabuoni Chapel frescoes, by Ghirlandaio and many assistants, were painted in four courses along the three walls, the main subjects being the lives of the Madonna and St. John the Baptist. These works are particularly interesting in that they include many historical portraits, a genre in which Ghirlandaio was preeminently skilled. |

||

|

||

|

||

Domenico Ghirlandaio: Zachariah in the Temple [detail]: Marsilio Ficino, Cristoforo Landino, Angelo Poliziano and Demetrios Chalkondyles,1486-1490.. Fresco. Santa Maria Novella, Cappella Tornabuoni, Florence |

||

| The Tornabuonichapel was completed in 1490; the altarpiece was probably executed with the assistance of Domenico's brothers, Davide and Benedetto; the painted window was from Domenico's own design. | ||

| The Birth of the Virgin |

||||

|

||||

Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Birth of the Virgin, (1486-90), Santa Maria Novella church, Tornabuoni Chapel, Florence |

||||

On the lower register of the opposite wall, as a witness to the Birth of the Virgin Mary which takes place in a contemporary Florentine bedroom, another young Tornabuoni woman, Lodovica, the only daughter of the patron stands in front of a group of companions. Her pose is almost identical to Giovanna degli Albizzi's and she wears a giornea of the same fabric and colour, decorated with the same heraldic motifs. In 1490 Lodovica was only fourteen, and she appears to the viewer as the ideal young virginal girl, modest and beautiful. A younger version of her characteristic profile can be seen in a medal, almost certainly cast in 1486. On the reverse of the medal, a unicorn, symbol of virginity, kneels in front of a dove perched on a tree — and a dove on a branch is one of the motifs woven into her gold brocade gown. In 1491 Ludovica married Alessandro di Francesco Nasi, whose portrait is painted next to that of her brother Lorenzo in the Joachim story. One of his most ambitious works was a series of frescoes for the choir chapel in the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. The frescoes illustrated the life of the Virgin and St John the Baptist. The Birth of the Virgin, imagined as childbirth in the palazzo of a great Florentine family. Men were excluded from childbirth. |

||||

| This study for The Birth of the Virgin must have been drawn at a very early stage as the architectural setting was refined in later drawings. Ghirlandaio's principal aim here appears to have been the arrangement of the figures. These are shown as spindly bodies with blank ovals for heads and blobs as hands - a technique strikingly similar to Michelangelo's in some of his preliminary compositional sketches. |

||||

| Ghirlandaio's compositional schemes were simultaneously grand and decorous, in keeping with the 15th century's restrained and classic experimentation. His chiaroscuro, in the sense of realistic shading and three-dimensionalism, was reasonably advanced, as were his perspectives, which he designed on a very elaborate scale by eye alone, without the use of sophisticated mathematics. His colour is more open to criticism, but such evaluation applies less to the frescoes than the tempera paintings, which are sometimes too broadly and crudely bright. His frescoes were executed entirely in buon fresco which, in Italian art terminology, refers to abstention from additions in tempera.

Ghirlandaio died of pestilential fever and was buried in Santa Maria Novella. The day and month of his birth remain undocumented, but since he died in early January of his forty-fifth year, he most likely did not reach that birthday. |

||||

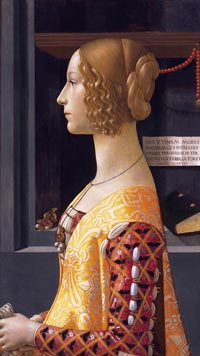

| Ghirlandaio incorporated portraits of his contemporaries in many biblical scenes. It is probably for precisely that reason that he was so popular among the rich Florentines, who were particularly keen on self portrayal. This makes it all the more astonishing that so few secular portraits by Ghirlandaio have survived. There are two paintings dating from about 1490, in the Paris Musée du Louvre and in Madrid, that are masterpieces of his art and yet fundamentally different: Giovanna Tornabuoni is idealized to the extent of becoming an "icon" of beauty for young Florentine girls, while the old man with the boy is painted with a pitiless degree of realism. Ghirlandaio does not shrink even from depicting his nose in all its disfigurement. The painting in Madrid depicts Giovanna degli Albizzi in a magnificent garment made of gold brocade with tight, slitted silk sleeves. She came from one of the most important Florentine families and in 1486 married Lorenzo Tornabuoni. After her early death Ghirlandaio created two portraits, and it is possible that he was able to produce the cartoon for them while she was still alive. In a fresco in the Tornabuoni Chapel, Giovanna is depicted as an entire figure witnessing the Visitation. The artist used that portrait in his panel painting with a new background, though he unfortunately cut the arms and hands off rather awkwardly. The delightful young woman now stands out, in a clear contrast of light against dark, from the black niche in the background. The reserved beauty of the young woman is fittingly expressed in the formal clarity of the composition. She is wearing a valuable piece of jewelry, comprising a ruby in a gold setting with three silky shining pearls, hanging from her neck by a delicate cord. There is a very similar item of jewelry on the shelf behind her, and this, combined with red coral beads against the black background, gives the work a noble elegance. These beads are part of a rosary, and the section that is hanging straight down emphasizes the vertical line of her back, and also directs our gaze to the prayer book. Between these two "pious" objects is a little note alluding to the beautiful soul of the portrayed woman by means of an epigram written by the Roman poet Martial in the first century A.D.: Ars utinam mores animumque effigere posses pulchrior in terris nulla tabella foret. (Art, if only you could portray mores and spirit, there would be no more beautiful picture on earth). This outstanding portrait, one of the most famous of the Quattrocento, makes it clear that portraits of women were one of Ghirlandaio's ideal subjects.

|

||||

|

|

|

||

Profile Portraits |

||||

The profile view commonly used for early Renaissance painted portraits conforms to the format of portrait medals, which Pisanello introduced in the 1430s. His Cecilia Gonzaga, representing the daughter of the duke of Mantua, is the first known Renaissance medal to portray a woman. Reflecting the humanist fascination with the classical past, medals emulated ancient Roman coins depicting the Caesars in strict profile. As the profile view was also used for images of female saints, it was eminently suitable for portraits of young brides, who were expected to bring honor to their husbands' families through virtuous behavior. The upright posture and averted gaze dictated by the profile format reinforced the impression of moral rectitude and echoed the Renaissance theorist Leon Battista Alberti's admonition that young women should comport themselves with self-restraint and "a grave demeanor." The painted profile portrait generally went out of vogue in the late fifteenth century, although it was still used under special circumstances. Domenico Ghirlandaio's Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, for example, is a posthumous portrait, apparently commissioned by Giovanna's husband to preserve the memory of his young wife, who had died in childbirth. In 1488 Domenico Ghirlandaio painted a half-length profile portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni, daughter of one of the most powerful families in quattrocento Florence. While the identity of the figure has never been disputed, the means of arriving at this attribution are worth reconsidering. A more secure way will be proposed. The portrait, traditionally viewed as posthumous, was indeed painted during Giovanna's lifetime. Neither the profile nor the integrated titulus, or inscription (previously argued), nor the other background objects point to a memorial portrait. Moreover, an identical portrait of Giovanna in the Cappella Tornabuoni solidifies an almost exact date for the Ghirlandaio panel. A close examination of Giovanna's dress and accessories -- jewels, book, coral chain, and written sheet -- reveals an upper-class, quattrocento interior, largely void of iconographic connotations. Especially the titulus in the painting's background, taken from Martial but brilliantly modified, must not be read as a reference to the concept of virtue and beauty but as an art-heoretical statement. Furthermore, Ghirlandaio's presentation of Giovanna's beauty corresponds with various descriptions in contemporary sources and focuses primarily on her physical appearance and less on her inner virtues. |

|

|||

.

|

||||

| In this detail Giovanna Albizzi-Tornabuoni is standing directly underneath the arch of a classical triumphal archway flanked by columns, just as if she were the main figure in the painting. In 1486 she married Lorenzo, the son of the donor. Vasari mistakenly thought she was "Ginevra de' Benci, a most beautiful young girl living at the time", whose portrait was painted by Leonardo da Vinci about 1478. Giovanna, who is standing stiff and rigid, is shown in sharp profile, wearing a magnificent gleaming gown and has an elegant hairstyle, unapproachable in front of her companions.

The two figures stepping out through the classical gateway make it clear just how monumentally large, and how far away, the building behind them is. |

||||

| This picture is frequently compared with another double portrait by Ghirlandaio of an old man and a young boy in the Musée du Louvre, Paris. Nancy Edwards dates it about 1488, perhaps on the occasion of Sassetti's departure for Lyons, adding that the purse at Sassetti's belt is an "article of dress [that] appears frequently in paintings of the period depicting scenes of travel"; suggests that the work may not have been able to be painted from life, which could explain the idealized features.[3] In his double portrait in the Musée du Louvre, the artist succeeds not only in portraying the two figures with great tenderness, but also in conveying the deep affection between them. The boy is gently snuggling up to the old man. Their eyes meet on a diagonal: this balances the composition, and also excludes the observer from the intimate scene. The boy is looking upwards along the old man's outline, which means that he is actually looking directly at the enormous nose projecting towards him. The contrast makes the little boy's snub nose, and the way his mouth is opened in astonishment, appear all the more childlike. The old man is sitting in the corner of a room in front of an open window The delicacy of the beautiful view of the landscape is, so to speak, a commentary on the profound companionability of the two generations. A soft light is falling an the faces through the window, and the old man is lit from the right and the boy from above. As the lit halves of their faces are turned towards each other, and the same bright red is used for the garments and cap, producing a richness that contrasts with the gray wall behind, the two figures seem to merge to form one. The picture is entirely composed with their unity in mind. Flemish influences are unmistakable in both the choice of the corner of the room and the landscape, bringing to mind both Dirck Bouts' Portrait of a Man in London dating from 1462 and several portraits by Petrus Christus. The identity of the sitters is no longer known, it cannot be stated with certainty whether they are indeed, as is supposed, grandfather and grandson. The man's nose, disfigured by a skin disease called rhinophyma, has in recent years led to the writing of several medical essays. Scratches in the paint layer disfigured it even further. This damage was removed by restoration work carried out in 1996. |

||||

Last Supper |

||||

Ghirlandaio painted the scene of the Last Supper on several occasions within the space of a few years. In all three works of his that still remain, the basic arrangement is the same as that in the fresco by Andrea del Castagno in the Florentine Cenacolo di Sant'Apollonia dating from about 1450. |

||||

The disciples are sitting at a long table in front of a rear wall that runs parallel to the picture plan. Christ is sitting in the centre, and His favourite disciple John is leaning sadly against Him. To the right of Christ, in the place of honour, is the chief Apostle, Peter. Judas the traitor is the only one to be separated from the others: he is seated in front of the table. |

||||

| The mosaic depicting the Annunciation in the lunette above the Porta della Mandorla in the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. Made by the brothers Domenico and David Ghirlandaio, it is one of the finest examples of wall mosaics ever made; the central portion of the mosaic bears the date of 1490. In addition to the fresco in the Tornabuoni Chapel in Santa Maria Novella, Ghirlandaio created another Annunciation between 1489 and 1490 using the ancient mosaic technique, which he had learnt from Alessio Baldovinetti and which he had been able to employ when restoring a few old mosaics. There is no lectern in this mosaic version of the Annunciation, though the influence of Leonardo's painting is still felt, particularly in the spatial arrangement - a building on the left behind Mary and a view over a wall to a landscape. |

Mosaic depicting the Annunciation in the lunette above the Porta della Mandorla in the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence |

|||

| Ghirlandaio was considered by his contemporaries to be one of the best painters of his generation. In the 19th century, however, the degree of realism in his work was decried by critics, who appreciated him only for his decorative qualities. His work has been reevaluated since the 1960s, and he is now regarded as one of the most eloquent and elegant narrators of Florentine society at the end of the 15th century. | ||||

Robert Baldwin, Ghirlandaios Sassetti Chapel

|

||||

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia article Domenico Ghirlandaio, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Domenico Ghirlandaio and the the Cappella Sassetti ("Sassetti chapel"), a chapel in Santa Trinita church, Florence. Cappella tornabuoni frescoes in Florence. Annuncio dell'angelo a San Zaccaria | File with annotations about. Move the mouse pointer over the image to see them. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. |

||||

Residency in Tuscany for writers and artists | Podere Santa Pia

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, giardino |

Cypress trees between San Quirico d'Orcia and Montalcino, one of the bird trapping techniques to capture wild birds. |

||

|

||||

Siena, Palazzo Sansedoni |

Choistro dello Scalzo, Florence |

|||

The façade and the bell tower of San Marco in Florence |

Monteriggioni |

Florence, Duomo |

||

The Church of Ognissanti was founded in 1251 by the Ordine degli Umiliati, rationalized the organization of the hamlet located on the site (it was outside the city walls at the time), which was specialized in woolworking. Address: Via Borgognissanti 42 - Florence |

|

|||

Church of Ognissanti

Church of Ognissanti