|

|

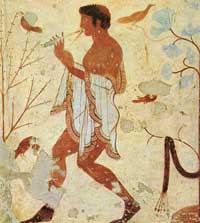

Tomba delle Leonesse (The Tomb of the Lioness), Necropolis of Tarquinia The wide ceiling of the tomb is decorated with a brown and white chessboard pattern |

|

|

Tarquinia, a medieval town famous for its archeological remains, is situated just a few kilometres from Tuscany, in Northern Lazio, very close to Capalbio and Monte Argentario and less than an hour drive from Podere Santa Pia. |

|

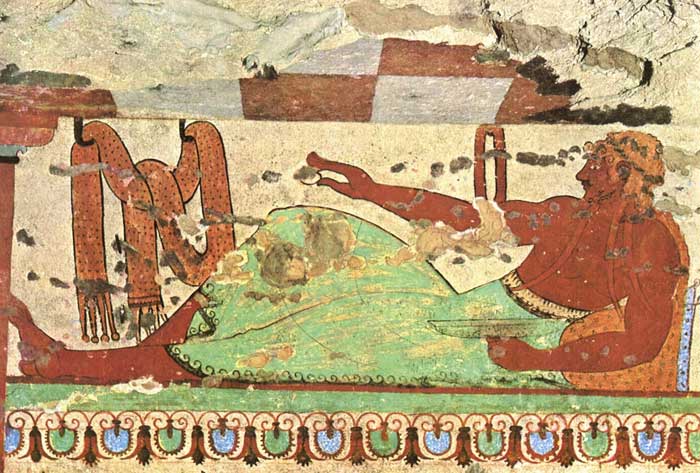

The man on the right wall, offering an egg, Tomba delle Leonesse, Necropolis of Tarquinia.

The egg is a common symbol of the Etruscan "afterlife. |

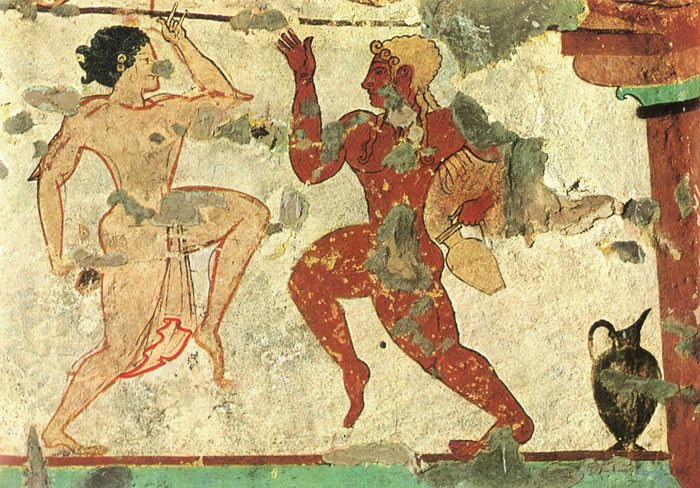

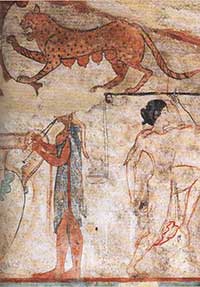

| The necropolis of Monterozzi in Tarquinia is famous for its painted tombs, also dug into rock and accessible by means of inclined corridors or stairways. It was realized predominantly for one couple and is composed of one burial room. The first tombs were painted in the 7th Century, but it is only from the 6th Century that they were completely covered in frescoes.[0] Both the painted tombs of the nobles and those in more simple styles are singular and extraordinary testaments to Etruscan quotidian life, as well as their ceremonies, mythology and even their artistic capacities. The frescoes inside the tombs – true-to-life reproductions of Etruscan homes – are faithful depictions of this disappeared culture’s daily life. These tumuli or burial mounds reproduce the homes in their various types of constructions; because they were built to mirror the Etruscan habitation itself, they are the only examples left of such in any form anywhere. The necropolis of Monterozzi in Tarquinia contains some 200 painted tombs, of a quality indicating the nobility of the people buried there. The most famous of these is probably the Fowling and Fishing Tomb with its polychrome frescoes painted about 520 BCE. The tombs of the Lionesses, of the Augurs, and of the Bacchantes (all 6th century BCE) show dancing and banqueting scenes. The Tomb of the Triclinium is the most outstanding 5th-century painted tomb, and the Tomb of the Shields is a masterpiece of 4th-century painting. A di stinctive 2nd-century painting tradition, rare in Etruria, is found in the paintings of the Tomb of the Cardinal. A serious conservation problem has arisen as many of the paintings have been attacked by moisture and fungus since the collection was opened to the public.[2] Of the most famous, the Tomb of the Lionesses dates back to the 4th Century, and consists of a small room with a two-sloped roof. Here, the painting features birds flying and dolphins jumping around scenes of the Etruscan aristocracy. The Hunter’s Tomb, also 4th Century, is presented as the inside of a tent, a pavilion with a wooden support structure. The Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, then, is one of the best-known and most studied; composed of two rooms, the first is complete with a fresco of a Dionysian dance in a sacred wood, while the second offers a scene of the tombs' owners hunting and fishing.[1] |

|

Woman wearing a tutulus, detail of the rear wall of the Tomba delle Leonesse, Tarquinia

|

| The Tomb of the Lioness |

In 'Etruscan Places', D.H. Lawrence describes his visits to various Etruscan sites, including the painted tombs of Tarquinia. His writing is less descriptive than that of the first two books. He is concerned with nothing less than the meaing of life, and the conflict between religion and truth (he died a few short years later at age 44 so his reflections seem almost prescient). He muses that societies are organized around death or life. He speaks of the use of fertility symbols such as fish and lambs for Christians and dolphins and eggs for Etruscans; the significance of the color vermillion -- male body painting by warrior classes where red paint connotes power contrasted with the the red skin coloring of the Etruscan tomb portraits which seems to have connoted the blood of life. He says the Etuscans loved life and the Romans who subdued them loved power.

|

|

||||

Dancers, Tarquinia, Tomb of the Lionesses. The young man carries a metal olpe, or jug, and in the young lady's right hand are castanets. |

||||

[0] UNESCO World Heritage Sites | The Necropolises of Tarquinia and Cerveteri

|

||||

| Monuments and Archaeological Sites Opening Times The Calvario area of the Monterozzi necropolis is open to the public all days except mondays and public holidays. Tusday - Sunday starting from 08.30 a.m. to 05.00 p.m. in the winter time Tusday - Sunday starting from 08.30 a.m. to 07.00 p.m. in the summer time The other main necropolis in Tarquinia is the Scatolini necropolis, which include the tomb of the Charontes. This is situated across the main road from the Monterozzi necropolis. The National Etruscan Museum |

Tarquinia, Tomb of the Lionesses |

|||

|

||||

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles Etruscan art and D. H. Lawrence, published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Siena, duomo |

Podere Santa Pia |

Sansepolcro |

||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, garden view in April |

||||