|

|

I T |

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel bay 4, The Fall and Expulsion from Garden of Eden, 1509-10, 'And the human called his woman's name Eve, for she was the mother of all that lives. And the LORD GOD make skin coats from the human and his woman, and He clothed them. And the LORD GOD said, Now that the human has become like one of us, knowing good and evil, he may reach out and take as well from the tree of life and live forever. And the LORD GOD sent him from the Garden of Eden to till the soil from which he had been taken. And He drove out the human and set up east of the Garden of Eden the cherubim and the flame of the whirling sword to guard the way to the tree of life.' [Genesis 3] |

The Fall and Expulsion from Garden of Eden |

| The doctrine of the fall of man is extrapolated from Christian exegesis of Genesis 3. According to the narrative, God creates Adam and Eve, the first man and woman, in His own image. God places them in the Garden of Eden and forbids them to eat fruit from the "tree of knowledge of good and evil" (the fruit of which is often symbolised in European art and literature as an apple). The serpent tempts Eve to eat fruit from the forbidden tree, which she shares with Adam and they immediately become ashamed of their nakedness. Subsequently, God banishes Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, and places cherubim to guard the entrance, so that Adam and Eve will not eat from the "tree of life". In Christian theology and Islam, the fall of man, or the fall, was the transition of the first man and woman from a state of innocent obedience to God to a state of guilty disobedience. Though not named in the Bible, the doctrine of the fall comes from Genesis chapter 3. At first, Adam and Eve live with God in the Garden of Eden, but the serpent tempts them into eating the fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, which God forbade. After doing so, they became ashamed of their nakedness and God expelled them from the Garden to prevent them from eating of the tree of life and becoming immortal. For many Christian denominations the doctrine of the fall is closely related to that of original sin; ie., they believe that the fall brought sin into the world corrupting the entire natural world, including human nature, causing all humans to be born into original sin, a state from which they cannot attain eternal life without the grace of God. The Eastern Orthodoxy accepts the concept of the fall but rejects the idea that the guilt of original sin is passed down through generations, based in part on the passage Ezekiel 18:20 that says a son is not guilty of the sins of his father. Calvinist Protestants believe that Jesus gave his life as a sacrifice for the elect, so they may be redeemed from their sin. Other religions, such as Judaism and Gnosticism, do not have a concept of "the fall" or "original sin" and have varying other interpretations of the Eden narrative. The term "prelapsarian" refers to the sin-free state of humanity prior to the fall. Interpretations |

Immortality |

||||

| In Gnosticism, the snake is thanked for bringing knowledge to Adam and Eve, and thereby freeing them from the Demiurge's control. The Demiurge banished Adam and Eve, because man was now a threat. Ancient Greek mythology held that humanity was immortal during the Golden Age[citation needed]. When Prometheus gave the gift of fire to humans, helping them live through times of cold weather, the gods were angered. They gave Pandora a box and told her not to open it, knowing full well that her curiosity would get the better of her. When she opened the box, she released evil (death, sorrow, plague) into the world due to her curiosity. See Ages of Man for more. In classic Zoroastrianism, humanity is created to withstand the forces of decay and destruction through good thoughts, words and deeds. Failure to do so actively leads to misery for the individual and for his family. This is also the moral of many of the stories of the Shahnameh, the key text of Persian mythology. Painting Giovanni di Paolo |

|

|||

| Giovanni di Paolo di Grazia, one of the most important Italian painters of the 15th-century Sienese school. He is chiefly notable for carrying the brilliantly colourful vision of Sienese 14th-century paintings on into the Renaissance. 'This masterpiece of Sienese painting presents a vision of Paradise reminiscent of that described by the great Florentine poet Dante in "The Divine Comedy." The universe is shown as a celestial globe, with the earth at the center surrounded by a series of concentric circles representing first the four elements, the known planets (including the sun, in accordance with medieval and Renaissance cosmology), and finally the constellations of the zodiac. Presiding over the scene of Creation is God the Father, bathed in a glowing celestial light as he is borne aloft by seraphim. Beside the "mappamondo" (map of the world) is the garden of Paradise, its four rivers issuing from the ground at the lower right. The garden's effulgent flora symbolize the pure and sinless state of man before the Fall. A diminutive Adam and Eve are expelled from the garden by a lithe angel whose unusual nakedness and human form may symbolize his deep compassion for the corrupted state of humankind after the fall from grace. This panel was originally at the far left of the predella from Giovanni di Paolo's Guelfi Altarpiece formerly in the Church of San Domenico in Siena (now Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence). It originally joined a representation of Paradise.'[6] Giovanni di Paolo | The Annunciation and Expulsion from Paradise |

|

|||

Giovanni di Paolo | The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise |

||||

|

||||

Giovanni di Paolo, The Creation and the Expulsion from the Paradise, c. 1445, tempera and gold on wood, 46, 4 x 52,1 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

||||

Masaccio and Masolino di Panicale | Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||||

|

||||

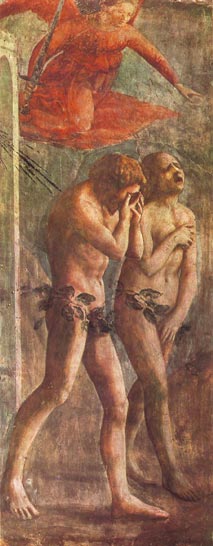

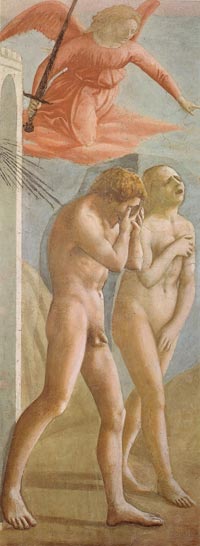

Masaccio, The Expulsion Of Adam and Eve from Eden, Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Firenze |

||||

| Masaccio’s fresco depicting Adam and Eve being expelled from the Garden of Eden by an angel is located in the Brancacci Chapel inside the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. The fresco is part of a larger cycle he painted for part of the chapel, while another painter, Masolino, worked on another fresco on the opposite wall of the chapel. The 12 frescoes were painted in two rows, six above and six below, that run around three walls of the chapel. The top row starts and ends at the beginning - in Eden - with one of the most famous events in the broad sweep of Judeo- Christian doctrine: on the right, Masolino depicts Adam and Eve at the moment just before the Temptation and the Fall (right). Balancing that view on the left side is Masaccio's interpretation of the expulsion from the Garden (pp. 94, 95). The painters have left us two distinctly different views of the hapless pair. In the "before" scene, Masolino is scrupulous about the details. The fig (not apple) tree is botanically correct. Its leaves and even the glistening seeds of its fruit are carefully depicted. And there is no need for Adam and Eve to cover themselves. Eden was created without a hint of evil. By contrast, meticulous draftsmanship was the last thing on Masaccio's mind. Working swiftly on his "after" view, with confident strokes he congealed the nightmare. In a vain attempt to hide, Eve covers herself. Adam is crushed; cradling his head in his hands, he is overcome with remorse. The rest of the top register of frescoes and all of the bottom are devoted to the life and acts of Saint Peter. Here we can see the Masolino-Masaccio collaboration, highlighting as it does now the turning point between Gothic and Renaissance art.[9] |

|

|||

Masaccio's Expulsion from the Garden of Eden is the first fresco on the upper part of the chapel, on the left wall, just at the left of the Tribute Money. It is famous for its vivid energy and unprecedented emotional realism. It depicts the expulsion from the garden of Adam and Eve, from the biblical Book of Genesis chapter 3, albeit with a few differences from the canonical account. It contrasts dramatically with Masolino's delicate and decorative image of Adam and Eve before the fall, painted on the opposite wall. |

||||

The main points in this painting that deviate from the account as it appears in Genesis: |

|

|

||

| A hovering angel (so foreshortened that it appears ready to pounce) presides over the scene, driving Adam and Eve out into a world where toil and hardship and death will be their lot. Three centuries after the fresco was painted, Cosimo III de' Medici, in line with contemporary ideas of decorum, ordered that fig leaves be added to conceal the genitals of the figures. These were eventually removed in the 1980s when the painting was fully restored and cleaned. |

||||

|

Masolino da Panicale | Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||||

|

||||

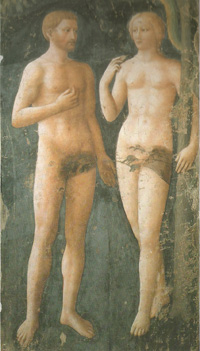

Masolino da Panicale, The Temptation, 1426-27, fresco, 208 x 88 cm, Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||||

| In this scene Masolino makes use of the most popular and traditional iconography of the period and the two figures, both in their gestures and in their expressions are courtly and elegant: a mood which has always been contrasted with the atmosphere in Masaccio's fresco on the opposite wall of the chapel, interpreted as a powerful manifesto of a new cultural and artistic vision, one of great spiritual harmony and technical ability.

The foliage, which had been addded in the 17th century to cover the nude bodies, has been removed during the recent restoration. |

|

|||

Art in Tuscany | Masolino da Panicale Masolino da Panicale | Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence |

||||

Michelangelo Buonarroti | Frescoes in the Sistine Chapel | The Fall and Expulsion from Garden of Eden |

||||

|

Masaccio provided a large inspiration to the more famous Renaissance painter Michelangelo, due to the fact that Michelangelo's teacher, Ghirlandaio, looked almost exclusively to him for inspiration for his religious scenes. Ghirlandaio also imitated various designs done by Masaccio. This influence is most visible in Michelangelo's "The Fall of Man and the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden" on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

|

||||

|

||||

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel bay 4, The Temptation and the Expulsion from Garden of Eden, 1509-10,

fresco, 280 x 570 cm, Cappella Sistina, Vatican |

||||

The Sistine Chapel is named after his commissioner, Sixtus IV della Rovere (1471-1484).

|

|

|||

|

||||

[10] Graham-Dixon, Andrew (2008), Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p1 Bibliography |

||||

|

||||

|

This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Fall of man, Masaccio and Brancacci Chapel, published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

| Wine regions | Podere Santa Pia |

Siena, Palio |

||

Siena, Duomo |

Florence, Duomo |

Corridoio Vasariano, Firenze |

||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, morning view on the Maremma from the western terrace |

||||