| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Firenze

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Masolino da Panicale | Frescoes in the Cappella Brancacci of Santa Maria della Carmine in Florence

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The frescoes in the famous Brancacci Chapel in Florence, begun by Renaissance masters Masaccio and Masolino and completed by Filippino Lippi in 1487, served as a training ground and inspiration to a generation of painters from Raphael to Michelangelo. Partially obscured by smoke from votive lamps, air pollution, varnish and the effects of a 1771 fire, the frescoes, including the Life of Saint Peter cycle, were restored in 1981-88.

The Cappella Brancacci is a small chapel reached through the cloisters of the Santa Maria del Carmine Church. Most of the church was destroyed in a fire in 1771. It is considered a miracle that the Brancacci and Corsini Chapels survived the intense fire that destroyed everything else in less than 4 hours. The Church belongs to the Carmelite order, and like San Lorenzo, offers an unfinished façade.

Two layers of frescoes commissioned in 1424 by Felice Brancacci, a wealthy Florentine merchant and statesman, illustrate the life of St. Peter, shown in his orange gown. The frescoes were designed by Masolino da Panicale, who began painting them with his pupil Masaccio. In 1428 Masaccio took over from Masolino but died later that year, aged 27, and the remaining parts were completed by Filippino Lippi in the 1480s.

The chapel was recently superbly restored, with the removal of accumulated candle soot and layers of 18th century egg-based gum which had formed a mold. The frescoes have an intense radiance, making it possible to see very clearly the shifts in emphasis between Masolino's work and that of Masaccio (contrast the serenity of Masolino's Temptation of Adam and Eve with the excruciating agony of Masaccio's Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise).

The restoration also highlights Masaccio's mastery of chiaroscuro (light and shade), which, combined with his grasp of perspective, created much marvel and was consciously copied by the Florentine painters of the 15th century. His depiction of St. Peter healing the sick (left of the altar, lower register) showed beggars and cripples with revolutionary realism. The colors are so vivid today that it is hard to believe they were painted over five centuries ago.[3]

Masolino da Panicale is generally considered to be a member of the Florentine School, but he travelled a good deal and even went to Hungary. His career is closely linked to that of Masaccio, but the exact nature of the association remains ill-defined. The tradition that he was Masaccio's master is now dismissed, for he became a guild member in Florence only in 1423 (a year after Masaccio) and although he was appreciably the older man it was he who was influenced by Masaccio rather than the other way round. They are thought to have collaborated on The Madonna and Child with St Anne (Uffizi, Florence, c. 1425), but the major undertaking on which they worked together was the decoration of the Brancacci Chapel of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. Masolino's style was softer than Masaccio's and there is a fair measure of agreement about the division of hands. Masolino's contributions, completed between 1424 and 1427, include The Preaching of St. Peter, The Raising of Tabitha, and The Fall of Adam and Eve.

After Masaccio's death Masolino reverted to the more decorative style he had practiced earlier in his career. At his best he was a painter of great distinction, his masterpiece perhaps being the fresco of the Baptism of Christ (c. 1435) in the Baptistery at Castiglione d'Olona, near Como, a graceful and lyrical work that is a world away from Masaccio's Baptism of the Neophytes in the Brancacci Chapel. Other important frescoes were done for the Church of San Clemente, Rome; and for the Church of Sant'Agostino, Empoli.

|

The Brancacci Chapel or Cappella dei Brancacci is a chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. The frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel play a central role in any narrative of early fifteenth century Florentine painting. The pictorial innovations in a fresco like the Tribute Money by Masaccio, are given important emphasis in these histories. Masaccio's use of techniques like linear perspective, foreshortening, atmospheric perspective, cast shadows, unified light source, and contrapposto contribute to the coherent sense of space and light filled environment that seems like an extension of the viewer's space. While Masaccio in his approach to the formal elements is trying to make the scenes immediate to the viewer, the subject matter relates episodes from the life of St. Peter to concerns that would have immediate interest to a Florentine of the fifteenth century. Instead of the more usual Christological cycle, the subjects of the frescoes focus on the involvement of the church in the person of Peter in social life. Consider the frescoes and their likely textual sources, and see their relevance to civic life of Florence.

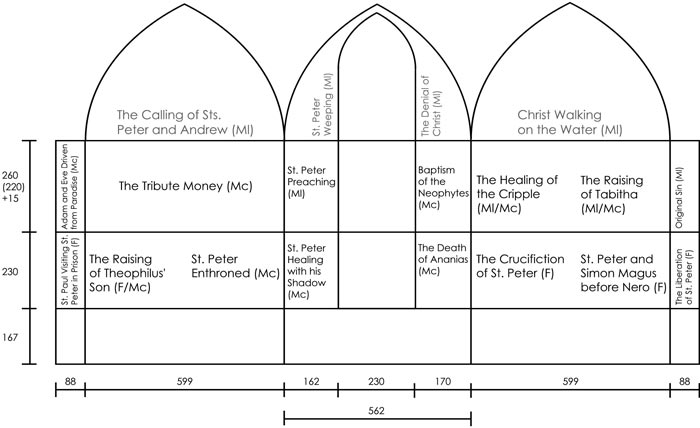

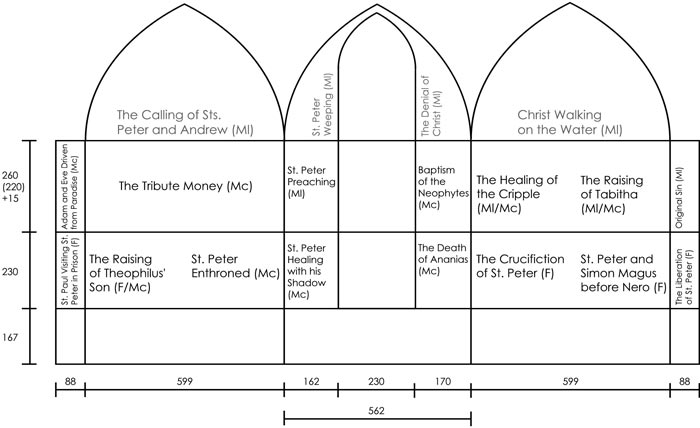

The chapel was the result of a bequest of Pietro Brancacci, who died in 1367. The choice of episodes from the life of the St. Peter as the subject matter of the frescoes likely reflects the wishes of Pietro. After the deaths of Pietro's brothers and sons, the chapel past down to a nephew, Felice Brancacci. It is understood that Felice was responsible for the commissioning of the frescoes. Felice's political alliance with Palla Strozzi was cemented by his second marriage to the daughter of Palla Strozzi. With the exile of Strozzi in 1434, Felice was charged with political intrigue and was himself exiled in 1435. The prominence of St. Peter in the Brancacci cycle perhaps also reflects Felice's strong ties to the Papacy in Rome. Although not certain, most scholars conjecture that Masolino was given the original commission of the work. He was responsible for the frescoes on the upper register of the right wall, while Masaccio was given responsibility for those on the left. They apparently shared responsibility for the altar wall. While Masaccio's activity can be seen in the lower register that was largely completed by Filippino Lippi, Masolino's work is limited to the upper register. A fire in 1748 destroyed the original frescoes in the vault and lunettes. Following the regular practice in fresco painting of beginning at the top and working down, it seems plausible that Masolino's activity began with the ceiling and then worked down to the upper register with Masaccio picking up at this point. [2]

The fresco cycle, with the exception of the first two, tells the story of St Peter, as follows:

Temptation (Masolino)

Expulsion from the Garden (Masaccio)

Tribute Money (Masaccio)

Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha (Masolino)

St Peter Preaching (Masolino)

Baptism of the Neophytes (Masaccio)

St Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow (Masaccio)

Distribution of Alms and Death of Ananias (Masaccio)

Raising of the Son of Theophilus and St Peter Enthroned (Masaccio and Filippino Lippi)

Disputation with Simon Magus and Crucifixion of St Peter (Filippino Lippi)

St Paul Visiting St Peter in Prison (Filippino Lippi)

Peter Being Freed from Prison (Filippino Lippi)

The frescoes in the upper register are: Adam and Eve in the Earthly Paradise, and Original Sin by Masolino, and the Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Earthly Paradise with the Tribute Money and the Baptism of the neophytes by Masaccio. Also by Masolino are the Preaching of St Peter with the Healing of the lame man and the raising of Tabitha. In the lower register, Masaccio painted the two scenes on the end wall, St Peter curing the sick with his shadow and the Distribution of goods, with The death ot Ananias.

|

| |

|

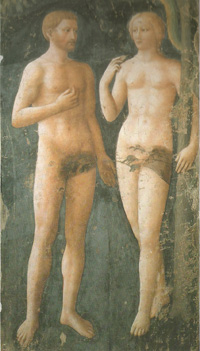

The 12 frescoes were painted in two rows, six above and six below, that run around three walls of the chapel. The top row starts and ends at the beginning - in Eden - with one of the most famous events in the broad sweep of Judeo-Christian doctrine: on the right, Masolino depicts Adam and Eve at the moment just before the Temptation and the Fall (right). Balancing that view on the left side is Masaccio's interpretation of the expulsion from the Garden.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Temptation

|

|

|

|

Masolino da Panicale, The Temptation, 1426-27, fresco, 208 x 88 cm, Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

|

| In this scene Masolino makes use of the most popular and traditional iconography of the period and the two figures, both in their gestures and in their expressions are courtly and elegant: a mood which has always been contrasted with the atmosphere in Masaccio's fresco on the opposite wall of the chapel, interpreted as a powerful manifesto of a new cultural and artistic vision, one of great spiritual harmony and technical ability.

The foliage, which had been addded in the 17th century to cover the nude bodies, has been removed during the recent restoration. |

|

|

|

|

|

Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha

|

| |

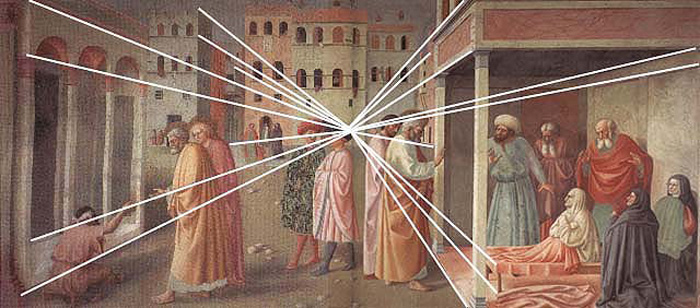

Masolino da Panicale, Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabatha, 1426-27, fresco, Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

|

Both the events depicted in this fresco are recounted in the Acts of the Apostles: the healing of the cripple in Jerusalem (3: 1-10) and the raising of Tabitha in Joppa (9: 36 43). Masolino sets both events in the same town although they had actually taken place in different cities and at different times.

In the square there are two elegantly dressed characters, in the centre of the scene, who separate but also provide the link between the two miraculous events. The presence of these two figures, and also the characters depicted in the background in front of the houses, makes the two events look like normal everyday occunences in the life of a city. The square resembles a contemporary Florentine piazza and the houses in the background, although none of them is strictly speaking an accurate portrayal of an existing building, convey the idea of Florentine architecture, as we still know it today. Even the paving of the street, different from that of the square, is a note of pure realism: the cobblestones, decreasing in size as they recede., also serve to emphasize the perspective of the composition.

And there are other elements which contribute to this description of everyday city life: the flower pots on the window sills, the laundry hanging out to dry,the bird cages, the two monkeys, the people leaning out of the windows to chat with their neighbours, and so on.

In the past the loggia to the left had been considered by critics to be architecturally fragile and unconvincing. But now, thanks to the restoration, we can make out the structural elements: from the smooth capitals of the pilasters, to the red plaster inside the courts.

And even in the righthand loggia, where the miracle. of the raising of Tabitha takes place, the classical, Albertian colour pattern of the surfaces and the entablatures increases the solidity of the architecture.

Throughout the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, scholars attributed this fresco to Masaccio, until 1929 when it was re-attributed to Masolino. Some critics claimed that there were sections painted by Masaccio. In 1940 it was suggested that Masaccio was responsible for the entire architectural background of the scene, including the figures in the background. This theory was accepted by almost all later scholars.

Since the restoration, now that the pictorial techniques can be clearly distinguished, we can rule out any intervention by Masaccio at all, at any rate in the actual execution. |

|

This detail shows the left side of the fresco with the scene Healing the Cripple

This detail shows the right side of the fresco with the scene Raising of Tabitha

|

St Peter Preaching

|

|

Masolino da Panicale, St Peter Preaching, 1426-27, fresco, 255 x 162 cm, Cappella Brancacci, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

|

The scene refers to Peter's sermon, as recounted in the Act of the Apostles, which he preaches in Jerusalem after the descent of the Holy Ghost on Pentecost. The fresco actually illustrates the final part of the sermon, when Peter says: "Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the remission of sins, and ye shall receive the gift of the Holy Ghost."

It was first suggested in 1940 that Masaccio must have had a hand in this fresco. The three bystanders to the left behind St Peter were attributed to Masaccio (their grim expression is truly modern). However, after the restoration, the cleaning has given such a clear vision of the pictorial fabric that we can now attribute the fresco entirely to Masolino, who was working in total autonomy, following an established division of spaces and subjects, in harmony with the corresponding scene of the Baptism paianted by Masaccio, according to a project that had been drawn up by the two artists together. |

|

|

| |

|

|

[1] Masolino was born in Panicale, in the Valdarno. The exact date of his birth is not known, but a likely date of around 1383 or 1384 can be deduced from documents. In 1422 he was living in Florence, where he rented a house and workshop. In 1423 he enrolled in the guild of doctors and pharmacists, which also included painters. In 1428, at the age of about forty-four or forty-five, he was liberated from his father's authority, assuming the legal status of head of family. His fresco cycle of 1435 in the baptistry of Castiglione Olona affords the last date recorded for him.

According to Vasari, Masolino's training began in Ghiberti's workshop and continued at the age of nineteen under Gherardo Starnina. Both pieces of information appear likely; Masolino may have been associated with Starnina about 1402-1403, when that artist, after his return from Spain, became a leading painter in Florence.

To explain the complete lack of record of Masolino in the first two decades of the fifteenth century, scholars have hypothesized the artist's long absence from his city; possibly he was in Hungary, were a sojourn is documented between 1425 and 1427. A Virgin and Child (Palazzo Vecchio, Florence) and a fragmentary Bust of the Virgin (private collection, Milan) could belong to an early undocumented period of activity in Florence at the beginning of the second decade.

A subsequent influence on Masolino's style was the subtle naturalism of Gentile da Fabriano. Nonetheless, the Bremen Madonna (1423), the Carnesecchi triptych for the church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Florence (of which only one panel remains in the Museo Diocesano in Florence), and the Madonna of Humility in Munich attest to his progress toward a more complete understanding of the physical density of forms and their convincing placement in pictorial space. The evolution of his idiom toward Renaissance models can also be seen in the frescoes in Santo Stefano and at the Collegiata in Empoli (1424), where the late Gothic tradition and new classical ideals are melded with extraordinary results.

It was probably in late 1424 or early 1425 that Masolino began to collaborate with Masaccio, who completed his Virgin and Saint Anne (Uffizi, Florence) and would work with him in the Brancacci chapel in the Carmine, also in Florence. It seems likely that the two painters began the cycle at the end of 1424 and interrupted their work definitively when Masolino left for Hungary.

Documents prove that Masolino reappeared in Florence only in May 1428, remaining in the city until March 1429. He then went to Rome, where he painted the Miracle of the Snow triptych in Santa Maria Maggiore (whose panels are now divided among the National Gallery, London; Museo di Capodimonte, Naples; and John G. Johnson collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art). In Rome, Masolino also frescoed the chapel of Saint Catherine in San Clemente and executed the (lost) frescoes representing famous men in Palazzo Orsini on Monte Giordano. In 1432 he painted a fresco of the Virgin and Child in the church of San Fortunato, Todi.

By 1435 Masolino was in Castiglione Olona near Varese, where he frescoed the Collegiata and the baptistry at the request of Cardinal Branda Castiglione, who had earlier commissioned the paintings for the chapel in San Clemente in Rome. The frescoes of the Collegiata were completed, presumably after Masolino's death, by Paolo Schiavo and Vecchietta in the late 1430s. Masolino's experience working with Masaccio resulted in a more rigorous sense of perspective and a search for effects of monumentality and compositional balance. After their collaboration was interrupted, Masolino's natural tendency toward a lively, colorful narrative style re-emerged, as proved by the Castiglione Olona frescoes where the artist pays tribute also to the art of Pisanello. [Masolino da Panicale - Biography | National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC]

[2] 'The foundation of the church dedicated to Our Lady of Carmel dates from 1268, but its construction was protracted until the end of the 15th century.

Little remains of the mediaeval building, not only because of the extensive 16th-century alterations but also because of a disastrous fire which gutted the church in 1771. What we see today is in large part the result of the late-baroque rebuilding carried out after the fire by Giuseppe Ruggieri. From that period date the paintings on the ceiling (Ascension of Christ) and in the dome (The Trinity and the Virgin in Glory with Saints of the Old and New Testament) by Giuseppe Romei and Domenico Stagi. The fire did not however affect the old sacristy, which still has its chapel with Scenes from the life of St Cecilia attributed to Lippo d’Andrea (c. 1400), the Brancacci Chapel in the right transept, or the Corsini Chapel in the left.(...)

The fire of 1771 also spared the Corsini Chapel, one of the jewels of the Florentine Baroque, built to contain the mortal remains of St Andrew Corsini (1301-74, canonised in 1629). Designed by the architect Pier Francesco Silvani, the chapel was decorated between 1675 and 1683 by Luca Giordano (frescoes in the dome, showing the Glory of St Andrew Corsini) and by Giovanni Battista Foggini (marble reliefs of St Andrew Corsini and the Battle of Anghiari, the Mass of St Andrew and the Apotheosis of St Andrew Corsini). Also saved was the marble funerary monument to Pier Soderini, by Benedetto da Rovezzano (1512-1513), placed inside the choir, behind the high altar.

Next to Santa Maria del Carmine stands the convent, rich in works of art. In the Room of the Column, looking onto the cloister, are displayed fragments of frescoes attributed to Pietro Nelli (c. 1385), other fragments from the Del Pugliese Chapel by Starnina (c. 1404), and a detached fresco of the Confirmation of the Rule by Filippo Lippi (1432). In the old refectory there is a Last Supper by Alessandro Allori (1582); in the second refectory there is the Supper in the house of Simon the Pharisee by Giovan Battista Vanni (c. 1645), and detached frescoes from the Nerli Chapel of Scenes from the Passion of Christ attributed to Lippo d’Andrea (1402). [Brancacci Chapel | www.museumsinflorence.com]

[3] Masaccio (1401–1428?) is the foremost Italian painter of the Florentine Renaissance in the early 15th cent. He was the first to apply to painting the laws of perspective discovered by Brunelleschi. His chief work is the frescoes in the Brancacci chapel in the church of Sta. Maria del Carmine,

Florence.

Masaccio's original name was Tommaso Guidi. He was enrolled in the guild of St. Luke in 1424. Most of the creations of his brief lifetime have perished. Only four remain that are attributed to him without question: a polyptych (1426) painted for the Church of the Carmine, Pisa, many of its panels dispersed (now in London, Pisa, Naples, and Vienna) and some lost; the great fresco in Santa Maria Novella, Florence, which revolutionalized the understanding of perspective in painting; Trinity the (Uffizi), an early work in collaboration with the painter ; and his Virgin with St. Anne Masolino da Panicale masterpiece — a major monument in the history of art — the frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel of Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, begun by Masolino and completed many years later by Filippino. Leaving the chapel unfinished, Masaccio Lippi went to Rome, where he died. Masaccio's independent works in the chapel include Expulsion from Eden, Peter and John and Healing the Sick, Peter and John Distributing Alms, Peter Baptizing, The Raising of the King's Son, The Tribute Money.

These frescoes had a great impact on Florentine painting and were for generations the training school and inspiration of painters, among them Michelangelo and Raphael. Masaccio imparted a new sense of grandeur and austerity to the human figure. He used light to give dimension to the contour and achieved a classic sense of proportion. At the same time he created a diversity of character within a unified group and emphasized the range of emotional expression in heroic individuals. Masaccio is remembered primarily for his innovative use of perspective. His originality and imagination place his work in the tradition of Giotto and Michelangelo.

Art in Tuscany | The technique of fresco painting

www.museumsinflorence.com | Brancacci_chapel

Bibliography

Umberto Baldini, Ornella Casazza, The Brancacci Chapel, ABRAMS, 1992

Olmert, Michael. "The new look of the Brancacci Chapel discloses miracles." Smithsonian Feb. 1990: 94+.

Expanded Academic ASAP. Web. 10 May 2011.

Adams, Laurie (2001). Italian Renaissance Art. Oxford: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3690-2.

Gardner, Helen (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed. ed.). San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

Ladis, Andrew (1993). The Brancacci Chapel, Florence. New York: George Braziller. ISBN 0-8076-1311-8.

Paoletti, John T. & Gary M. Radke (1997). Art in Renaissance Italy. London: L. King. ISBN 1-85669-094-6.

Shulman, Ken (1991). Anatomy of a Restoration: The Brancacci Chapel. New York: Walker. ISBN 0-8027-1121-9.

Watkins, Law Bradley (1980). The Brancacci Chapel Frescoes: Meaning and Use. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International. ISBN.

Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance painting

|

This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Masolino da Panicale and Brancacci Chapel, published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

| |

|

|

. |

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, December |

|

The Hospital of the Innocents, façade by Filippo Brunelleschi

|

Arcidosso |

|

Montalcino |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Santa Maria del Carmine, Firenze |

|

|

|

|

|

Lucca, Anfiteatro |

|

Florence, Orsanmichele

|

|

Florence, Duomo Santa Maria del Fiore

|

|

Podere Santa Pia has some wonderful views over the orchid valley below, and creates a perfect platform from which to enjoy the breathtaking scenery of this unique part of Italy

|

The technique of fresco painting

Sinopia painting

'To create a fresco, the painter began by coating the wall with a layer of plaster, which was made by mixing water with slaked lime, and large-grained river sand. This first layer, about one centimeter thick, is called the arriccio (rendering). The roughness of this surface promotes the adhesion of the second layer of plaster. The artist drew the preparatory drawing directly on this first layer. With a piece of charcoal - easily erasable - he first penciled in the design. Once satisfied with this drawing, he used earth-ochre to trace a second set of lines alongside the charcoal lines. A bunch of feathers was then used to brush away the charcoal lines, and a red earth pigment was used to draw over their faded yellow remnants and to flesh out the details of the representation (folds of drapery, faces, chiaroscuro, etc.). This technique, first introduced in the thirteenth century, was used during most of the fourteenth century for large preparatory drawings. Today sinopia painting is named after the reddish pigment (originally from the city of Sinope) used to execute the technique.

Once the sinopia painting was finished, the actual painting could begin. At this point a new layer of plaster, the ‘intonachino' (thin plaster layer) was spread over one area of the arriccio (rendering) to prepare a perfectly smooth surface to receive the coloring. Intonachino (thin plaster layer) is a thin, transparent layer composed of one part slaked lime and two parts finely-ground sand. It was only applied to the surface area the artist expected to be able to color during one day's work, because the surface must be humid during the coloring phase. Then the painter used a brush to trace over the sinopia painting outline, which remained visible through the thin layer of intonachino (thin plaster layer). At last, he began painting with grounded pigments mixed in water.

The technique of fresco painting consists of painting colour pigments onto a layer of plaster that is still wet or "fresh" as the Italian term fresco suggests.

Walls to be frescoed were normally constructed from a single material, generally stone or brick to prevent damage to the frescoes from any movement in the wall due to settlement.

The artist would begin by applying a layer of plaster, made from a mixture of water, slaked lime, and large-grained river sand, to the wall.

This first layer, known as the arriccio, was applied to a thickness of one centimetre. The surface had to be very rough to allow the second layer of plaster to adhere to it easily.

On top of the arriccio, the outline of the fresco was drawn in charcoal, which was then erased using feathers after a second outline had been applied in ochre. Over the ochre, another outline was added with a red pigment called sinopia, a term which came to be used to describe the preparatory drawings it was used for. Finally, a fine layer of plaster called intonachino or velo was applied. This was transparent and much smoother than the arriccio and was usually made from one part slaked lime and two parts finely-ground sand. The surface had to be perfectly smooth surface and remain wet throughout the entire painting process and was therefore only applied to an area that the artist could complete painting in one day. For this reason, each one of these sections came to be known as a giornata, or 'day's work'.

The painter began by copying the sinopia outline, which showed through from the layer underneath, onto the wet plaster, and then started to paint using ground pigments mixed with water. Faces were usually painted starting with light shades and progressing to darker ones. The opposite technique was used for clothing, in which dark shades followed lighter ones.

Not all pigments could be used. Indeed, when the plaster dries, the lime which it contained causes a chemical reaction called carbonation, which releases heat and can burn plant-based pigments. For this reason, some touching up was often required after the plaster had dried to perfect details. This technique is called a secco, or dry. Blues, too, had to be painted a secco. This was true for both the extremely costly lapis lazuli or ultramarine, and azurite or "German blue". By the mid 15th century, the sinopia technique began to be replaced with preparatory cardboard, or cartone. The drawings were done to a smaller scale on squared paper in the artist's workshop.

A larger-scale grid with the same number of squares was then drawn on a piece of paper the same size as the fresco. The smaller drawing was then copied onto the large one, enlarged square by square. Holes were poked in the large drawing using a big needle and a loosely-woven sack of coal dust was passed over it. This technique, known as spolvero or dusting, resulted in a continuous series of little dots which the artist would join together to create the drawing. During the Renaissance a third method was also developed in which the drawing, enlarged using the grid method, was transferred onto thin paper. This was laid over the fresh plaster and a long nail was used to trace the lines and transfer the composition onto the mortar.

Serena Nocentini | The technique of fresco painting | www.brunelleschi.imss.fi.it | Watch the movie

'Strappo' (Detachment)

During the 18th century, new techniques were perfected for the restoration and conservation of ancient works of art, including methods of detaching fresco paintings from walls.

Detachment involves the separating the layer of paint from its natural backing, generally stone or brick, and can be categorized according to the removal technique used.

The oldest method, known as the a massello technique, involves cutting the wall and removing a considerable part of it together with both layers of plaster and the fresco painting itself.

The stacco technique, on the other hand, involves removing only the preparatory layer of plaster, called the arriccio together with the painted surface.

Finally, the strappo technique, without doubt the least invasive, involves removing only the topmost layer of plaster, known as the intonachino, which has absorbed the pigments, without touching the underlying arriccio layer.

In this method, a protective covering made from strips of cotton and animal glue is applied to the painted surface. A second, much heavier cloth, larger than the painted area, is then laid on top and a deep incision is made in the wall around the edges of the fresco.

A rubber mallet is used to repeatedly strike the fresco so that it detaches from the wall. Using a removal tool, a sort of awl, the painting and the intonachino attached to the cloth and glue covering are then detached, from the bottom up.

The back of the fresco is thinned to remove excess lime and reconstructed with a permanent backing made from two thin cotton cloths, called velatini, and a heavier cloth with a layer of glue. Two layers of mortar are then applied; first a rough one and then a smoother, more compact layer.

The mortars make up the first real layer of the new backing. The velatini cloths and the heavier cloth serve only to facilitate future detachments, and are therefore known as the strato di sacrificio, or sacrificial layer.

Once the mortar is dry, a layer of adhesive is applied and the fresco is attached to a rigid support made from synthetic material which can be used to reconstruct the architecture that originally housed the fresco.

After the backing has completely dried, the cloth covering used to protect the front of the fresco during detachment is removed using a hot water spray and decoloured ethyl alcohol.'

Serena Nocentini | The technique of fresco painting | www.brunelleschi.imss.fi.it | Watch the movie

The Rise of Renaissance Perspective

|

|

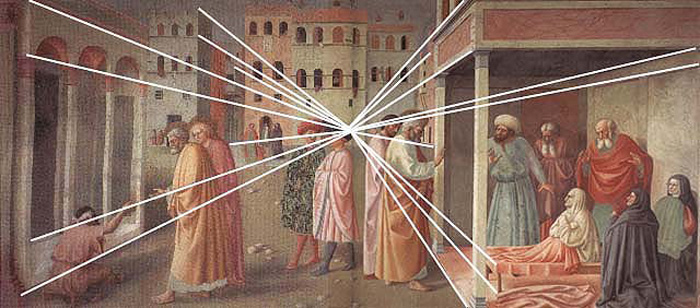

Masolino’s ‘St. Peter Healing a Cripple and the Raising of Tabitha’ (1425). Note the almost perfect convergence of the vanishing points for receding horizontals from all parts of the composition, from the front of the scene all the way to streets in the far distance. The occasional slips seem attributable to lack of attention rather than lack of understanding of the concept of the vanishing point.

|

To evaluate perspective accuracy, one needs to have a clear understanding of the rules of perspective. Three of its rules will be relevance to the present discussion. One is the rule of the central vanishing point. If we imagine a canvas set up before the scene to be painted, all edges receding from the canvas (at a right angle to it) will project to lines in the picture converging toward a single, central vanishing point (Fig. 1). This is the familiar one-point construction, which applies to a scene where all other edges are parallel to the surface of the canvas. The second rule applies to other lines or edges at various angles in the ground plane, or parallel to the ground plane. All edges parallel to the ground plane will have a vanishing point at the same level as the central vanishing point. In fact, all these vanishing points will be in the line of the horizon. Particular examples of such lines are those connecting the corners of a square grid projected in perspective (Fig. 2). These obliques project to a lateral vanishing point in both directions that should align with the central vanishing point. Slight deviations from such alignment betray that the method of construction did not rely on such vanishing points, instead using the technique of a diagonal (solid line in original) crossing the converging orthogonals. Each intersection defines the correct position for a transversal break in the tiling, but small inaccuracies in the measurements show up as deviations at the long remove of the lateral projections.

Although largely ignored in perspective histories, the central vanishing point appears to have been first used in 1423 by Masolino da Panicale (1383-c. 1440), and is well-illustrated by his painting from the same period of a double scene of miracles of St. Peter, which has a strong perspective construction (Fig. 3). Although the ground plane is rock-strewn earthen floor, almost all the receding horizontals in the buildings around the piazza conform accurately to a single vanishing point. This is the more remarkable because they span the visible depth from the front edge of the picture to the narrow streets in the far background (where the convergence requirements are close to parallel). Only someone with a thorough commitment to the principle of central convergence could have achieved this global level of uniformity. As shown in Fig. 3, one can find as many as 24 horizontals that converge to an accurate vanishing point, although 4 other lines deviate from this center by a small amount. As other early Quattrocento works show, the probability of finding this degree of convergence on the basis of intuitive construction alone is so small as to be negligible.

In the rest of the century following Masolino’s breakthrough, almost all Renaissance artists turned to the use of perspective to enhance their compositions, notably Masaccio, Mantegna, Fra Angelico and Leonardo. The Renaissance use of perspective reached its apogee at around 1500, as represented by the incandescent work of Raphael. [Source: Perspective: The Rise of Renaissance Perspective | www.webexhibits.org]

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()