|

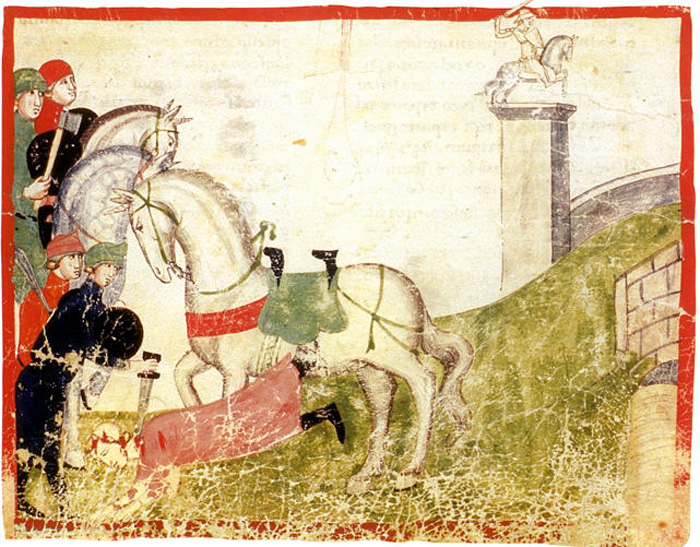

| Peter III of Aragon was wounded in 1285, Nuova cronica. f.137v (1.VIII,103) ms. Chigiano L VIII 296, Biblioteca Vaticana |

The Nuova Cronica | The Villani Chronicle |

| The Nuova Cronica or New Chronicles is a 14th-century history of Florence created in a year-by-year linear format and written by the Florentine banker and official Giovanni Villani (c. 1276 or 1280–1348). The idea came to him after attending a 1300 jubilee celebration in the city of Rome, where he realized that Rome's many historical achievements were well-known, and he desired to lay out a history of the origins of his own city of Florence.[2] In his Cronica, Villani described in detail the many building projects of the city, statistical information on population, ordinances, commerce and trade, education, and religious facilities. He also described several disasters such as famines, floods, fires, and the pandemic of the Black Death that took his life in 1348.[3][4] Villani's work on the Cronica was continued by his brother and nephew after his death.[2][5][6] It has been described as the first introduction of statistics as a positive element in history.[7]

|

Giovanni Villani's Cronica is divided into twelve books; the first six deal with the largely legendary history of Florence, starting at conventionally Biblical times to 1264.[5] The second phase, in six books, covers the history from 1264 until his own time, all the way up to 1346.[5] Villani outlines the events in his Cronica, not by theme, but through year-to-year accounts; for this, he has gained criticism over the years for writing in an episodic manner lacking a unifying theme or point of view.[8] Villani's chronicles are intercut with historical episodes reported just as he heard them, with little interpretation; this often led to historical inaccuracies in his work,[9] making most of his mistakes in the biographies of historical or contemporary people living outside of Florence (even with well-known monarchs).[10] However, his description of such events as the Battle of Crécy in 1346 was fairly accurate according to historian Kelly De Vries.[11] Both Bartlett and Green state that Villani's Cronica represented a departure from medieval chronicles in that a more modernistic approach was taken in describing events and statistics, yet still medieval in that Villani relied on divine providence to explain the outcome of events.[12][13] |

||

How the city of Florence was destroyed by Totila, the scourge of God, king of the Goths and Vandals |

||

|

||

'In the year of Christ 440, in the time of S. Leo the Pope, and of Theodosius and Valentinian emperors, in the northern parts there was a king of the Vandals and of the Goths, which was called Bela, and surnamed Totila. This man was a barbarian and had no religion, and was cruel in customs and in all things, born of the province of Gothland and Sweden, and in his cruelty he slew his brother and subdued many divers nations of peoples by his might and lordship; and afterwards he was minded to destroy and take away the Empire of the Romans, and lay Rome waste; and thus by his sovereignty he gathered together innumerable people from his own country, and from Sweden and from Gothland, and afterwards from Pannonia, which is Hungary, and from Denmark, to enter into Italy. And when he desired to pass into Italy, he was opposed by the Romans and Burgundians and French, and a great battle was fought against him in the district of Lunina, that is to say of Friuli and Aquilea, with the greatest number of slain that had ever been in any battle, both on one side and on the other; and the king of Burgundy was slain. And Totila, being discomfited, returned to his own country with the followers which were left to him. But afterwards, desiring to carry out his purpose of destroying the Empire of Rome, he gathered a larger army than before, and came into Italy. And first he laid siege to the city of Aquilea; so it continued three years, and then he took it, and burnt and destroyed it with all the inhabitants; and when he had entered into Italy, after the same manner he destroyed Vicenza, and Brescia, and Bergamo, and Milan, and Ticino, and well-nigh all the cities of Lombardy, save Modena, for the merits of S. Gemignano, which was bishop thereof; for when he was passing through this city with his people, by a divine miracle he did not see it save when he was without the city, and by reason of the miracle he passed it by, and did not destroy it: and he destroyed Bologna and put to martyrdom S. Proculus, bishop of Bologna, and thus he destroyed well-nigh all the cities of Romagna. And afterwards passing through Tuscany he found the city of Florence strong and powerful. Hearing the fame thereof, and how it had been built by the noblest Romans, and was the treasure-house of the Empire and of Rome, and how in this country had been slain Radagasius, king of the Goths, his predecessor, with so great a multitude of Goths, as before has been narrated, he commanded that it should be besieged, and long time he sat before it in vain. And seeing that he could not obtain it by siege, inasmuch as it was very strong in towers and in walls and in many good soldiers, he set about to gain it by deceit and by flattery and by treachery. Now the Florentines had continual war with the city of Pistoia; and Totila ceased laying waste the country around the city, and sent to the Florentines that he desired to be their friend, and in their service would destroy the city of Pistoia, promising and making show of great love, and to give them privileges with very generous covenants. The imprudent Florentines (and for this cause they were ever afterwards Inf. xv. 67. called blind in the proverb) believed his false flatteries and vain promises; they opened the gates to him, and admitted him and his followers into the city, and lodged him in the Capitol. And when the cruel tyrant was within the city with all his forces, under false seeming he showed love to the citizens, and one day he invited to his council the greatest and most powerful chiefs of the city in great numbers; and when they came to the Capitol, as they passed one by one through an entry, he caused them to be slain and massacred, none perceiving ought of the fate of the other; and afterwards he had them thrown into the ducts of the Capitol, to wit, the conduit of the Arno which flows underground by the Capitol, to the end that no man might know thereof. And thus he put them to death in great numbers, and nought was perceived thereof in the city of Florence save that at the exit from the city where the said aqueduct or conduit issued forth and flowed back into the Arno, the water was seen to be all red and bloody. Then the people perceived the deceit and treachery; but it was in vain and too late, seeing that Totila had armed all his followers; and when he perceived that his cruelty was discovered, he commanded them to overrun the city and slay both great and small, men and women, and from this there was no escape, forasmuch as the city was unarmed and unprepared, and we find that at that time there were in the city of Florence 22,000 men-at-arms, beside the aged and children. When the people of the city perceived that they were come to such sorrow and destruction, they escaped who could, fleeing into the country and hiding themselves in strongholds, and in woods and in caves; but the most part of the citizens were slain, or wounded, or taken, and the city was all despoiled of substance and riches by the said Goths, Vandals, and Hungarians. And after that Totila had thus wasted it of inhabitants and of goods, he commanded that it should be destroyed and burnt, and laid waste, and that there should not remain one stone upon another, and this was done; save that in the west there remained one of the towers which Gneus Pompey had built, and on the north and on the south one of the gates, and within the city near to the gate the "casa" or "domo," which we take to be the duomo of S. Giovanni, called of yore the "casa" [house] of Mars. And verily it never was entirely destroyed, nor shall be destroyed to eternity, save at the day of judgment, even as is written on the cement of the said duomo. And there were also left standing certain lofty towers or temples, indicated in the ancient chronicles by letters of the alphabet, the which we cannot interpret, to wit S, and casa P, and casa F. The city had four gates and six posterns, and there were towers marvellous strong over the gates. And the idol of the god Mars which the Florentines took from the temple and set upon a pillar, then fell into the Arno, and abode there as long as the city remained in ruins. And thus was destroyed the noble city of Florence by the infamous Totila 450 a.d. on the 28th day of June, in the year of Christ 450, to wit 520 years after its foundation; and in the said city the blessed Maurice, bishop of Florence, was put to death with great torments by the followers of Totila, and his body lies in Santa Reparata.'[a] |

||

|

||

Of Robert Guiscard and his descendants, which were kings of Sicily and of Apulia |

||

| The crowning of Robert Guiscard as a duke of Apulia and Calabria; by the 16th century, there were multiple versions of the Cronica in printed form as well as in illuminated manuscript form.[1] Pope Leo IX, a vigorous reformer from Alsace and a close ally of the Emperor Henry III, set out against the Normans with an army in 1053, but was routed at Civitate by 3,000 Norman horsemen, led by Count Humphrey with brother Robert commanding the left wing. According to one story, they took unfair advantage by attacking when a parley was in progress. The pope was taken prisoner and kept in polite captivity for nine months. Humphrey then personally escorted him as far north as Capua, but the experience is thought to have contributed to Leo’s death a month later.The battle was effectively the founding moment of the Norman empire in the south and the future kingdom of the Two Sicilies. When Humphrey died in 1057, Robert succeeded him, brushing aside his brother’s young sons. The papacy changed tactics and at Melfi in 1059 Pope Nicholas II invested Robert Guiscard as Duke of Apulia and Calabria and future lord of Sicily. |

||

|

||

Robert Guiscard claimed as a duke of Apulia and Calabria, Nuova Cronica, Vatican Library |

||

| 'Well, then, as was afore made mention, in the time of the Emperor Charles, which is called Charles the Fat, which reigned in the years of our Lord 880 unto 892, the pagan Northmen being come from Norway, passed into Germany and into France, pressing and tormenting the Gauls and the Germans. Charles, with a powerful hand, came against the Northmen, and peace being made and confirmed by matrimony, the king of the Normans was baptised, and received at the sacred font by the said Charles, and in the end, Charles not being able to drive the Normans out of France, granted them a region on the further side of the Seine, called Lada Serena, the which unto this day is called Normandy, because of the said Normans, in the which land, from that time forward, the duke has reigned as king. The first duke, then, was Robert, to whom succeeded his son William, which begat Richard, and Richard begat the second Richard. This Richard begat Richard and Robert Guiscard, the which Robert Guiscard was not duke of Normandy, but brother of Duke Richard. He, according to their usage, forasmuch as he was a younger son, had not the lordship of the duchy, and therefore desiring to make trial of his powers, he came, poor and needy, into Apulia, where at that time one Robert, a native of the country, was duke, to whom Robert Guiscard, coming, was first made his squire and was then knighted by him. Robert Guiscard having come then to this Duke Robert, won many victories with prowess against his enemies, for he was at war with the prince of Salerno; and carrying with him magnificent rewards, he returned into Normandy, bringing back report of the delights and riches of Apulia, having adorned his horses with golden bridles and shod them with silver, in witness of the facts he alleged; by the which thing, having roused many knights, following this emprise through desire of riches and of glory, returning incontinent into Apulia, he took them with him, and gave faithful aid to the duke of Apulia against Godfrey, duke of the Normans; and, not long time after, Robert, duke of Apulia, being nigh unto death, by the will of his barons made him his successor in the duchy, and as he had promised him, he took his daughter to wife the year of Christ 1078. And a little time after, he conquered Alexis, emperor of Constantinople, who had taken possession of Sicily and of part of Calabria, and he conquered the Venetians, and took all the kingdom of Apulia and of Sicily; and albeit he did this in violation of the Roman Church, to which the kingdom of Apulia belonged, and albeit the Countess Matilda made war against Robert Guiscard in the service of Holy Church; nevertheless, in the end, Robert being, of his own will, reconciled with Holy Church, was made lord of the said kingdom; and not long after, Gregory VII., with his cardinals, being besieged by the Emperor Henry IV. in the castle of S. Angelo, Robert came to Rome and drave away by force the said Henry with his Anti-pope which he had made by force, and he freed the Pope and the cardinals from the siege, and replaced the Pope in the Lateran Palace, having severely punished the Romans, who had shown favour to the Emperor Henry and to the Pope whom he had made against Pope Gregory. This Robert Guiscard, duke of Apulia, was once on a hunting excursion, and he followed the quarry into the depth of a wood, his companions not knowing what had become of him, or where he was, or what he was doing; and then Robert, seeing the night approaching, leaving the beast which he was pursuing, sought to return home; and turning, he found in the wood a leper, who importunately asked alms of him; and when he had said I know not what in reply, the leper said again that the anguish he endured availed him nought, yet him were liefer carry any weight or any burden; and when he asked of the leper what he would have, he said, "I desire that you will put me behind you on your horse"; lest abandoned in the wood, peradventure the beasts might devour him. Then Robert cheerfully received him behind him on his horse; and as they rode forward, the leper said to Robert—great baron as he was:—"My hands are so icy cold, that unless I may cherish them against thy flesh, I cannot keep myself on horseback." Then Robert granted the leper to put his hands boldly under his clothing, and comfort his flesh and his members without any fear; and when yet a third time the leper bespoke his pity, he put him upon his saddle, and he, sitting behind him, embraced the leper, and led him to his own chamber and put him into his own bed, and set him in it with right good care to the end he might repose; no one of his household perceiving ought thereof. And when the banquet of supper was spread, having told his wife that he had lodged the leper in his bed, his wife incontinent went to the chamber to know if the poor sufferer would sup. The chamber, albeit there were no perfumes therein, she found as fragrant as if it had been full of sweet-smelling things, such that neither Robert nor his wife had ever known so sweet scents, and the leper, whom they had come thither to seek, they did not find, whereat the husband and the wife marvelled beyond measure at so great a wonder; but with reverence and with fear, both one and the other asked God to reveal to them what this might be. And the following day Christ appeared in a vision to Robert, saying, that it was Himself that He had revealed to him in the form of a leper, to make trial of his piety; and He announced to him that by his wife he should have sons, whereof one should be emperor, the next king, and the third duke. Encouraged by this promise Robert subdued the rebels of Apulia and of Sicily, and acquired lordship over all; and he had five sons: William, who took to wife the daughter of Alexis, the emperor of the Greeks, and was lord and possessor of his empire, but died without children (some say that this was the William which was called Longsword, but many say that this Longsword was not of the lineage of Robert Guiscard, but of the race of the marquises of Montferrat); and the second son of Robert Guiscard was Boagdinos [Boemond], who was at the first duke of Tarentum; the third was Roger, duke of Apulia, which, after the death of his father, was crowned king of Sicily by Pope Honorius II.; the fourth son of Robert Guiscard was Henry, duke of the Normans; the fifth son, Richard Count Cicerat, that is, I suppose, count of Acerra. This Robert Guiscard, after having done many and noble things in Apulia, purposed and desired, by way of devotion, to go to Jerusalem on pilgrimage; and it was told him in a vision that he would die in Jerusalem. Therefore, having commended his kingdom to Roger, his son, he embarked by sea for the voyage to Jerusalem, and arriving in Greece, at the port which was afterwards called after him Port Guiscard, he began to sicken of his malady; and trusting in the revelation which had been made to him, he in no wise feared to die. There was over against the said port an island, to the which, that he might repose and recover his strength, he caused himself to be carried, and after being carried there he grew no better, but rather grievously worse. Then he asked what this island was called, and the mariners answered that of old it was called Jerusalem. Which thing having heard, straightway certified of his death,-89- devoutly he fulfilled all those things which appertain to the salvation of the soul, and died in the grace of God the year of Christ 1110, having reigned in Apulia thirty-three years. These things concerning Robert Guiscard may in part be read in chronicles, and in part I heard them narrated by those who fully knew the history of the kingdom of Apulia.'[a] |

||

How the city of Florence took fire twice, whence a great part of the city was burnt. 1115 a.d. |

||

|

||

| 'In the year of Christ 1115, in the month of May, fire broke out in the Borgo Santo Apostolo, and was so great-96- and impetuous that a good part of the city was burnt, to the great hurt of the Florentines. And in that selfsame year died the good Countess Matilda. And after, in the year 1117, fire again broke out in Florence, and of a truth that which 1117 a.d. was not burnt in the first fire was burnt in the second, whence great hurt befell the Florentines, and not without cause and judgment of God, forasmuch as the city was evilly corrupted by heresy, among others by the sect of the epicureans, through the vice of Cf. Inf. x. 13-15. licentiousness and gluttony, and this over so large a part, that the citizens were fighting among themselves for the faith with arms in their hands in many parts of Florence, and this plague endured long time in Florence till the coming of the holy Religions of St. Francis Par. xi. 35-123. Par. xii. 31-111. and of St. Dominic, the which Religions through their holy brothers, the charge of this sin of heresy having been committed to them by the Pope, greatly exterminated it in Florence, and in Milan, and in many other cities of Tuscany and of Lombardy in the time of the blessed Peter Martyr, who was martyred by the Paterines in Milan; and afterwards the other inquisitors wrought the like. And in the flames of the said fires in Florence were burnt many books and chronicles which would more fully have preserved the record of past things in our city of Florence, wherefore few are left remaining; for the which thing it has behoved us to collect from other veracious chronicles of divers cities and countries, great part of those things whereof mention has been made in this treatise.'[a] |

||

How the Florentines took and destroyed the fortress of Fiesole |

||

|

||

'In the year of Christ 1125, the Florentines came with an army to the fortress of Fiesole, which was still standing and very strong, and it was held by certain gentlemen Cattani, which had been of the city of Fiesole, and thither resorted highwaymen and refugees and evil men, which sometimes infested the roads and country of Florence; and the Florentines carried on the siege so long that for lack of victuals the fortress surrendered, albeit they would never have taken it by storm, and they caused it to be all cast down and destroyed to the foundations, and they made a decree that none should ever dare to build a fortress again at Fiesole.'[a] |

||

|

||

How the parties of the Guelfs and Ghibellines arose in Florence | The Buondelmonte murder |

||

|

||

The Buondelmonte murder, from an illustrated manuscript of Giovanni Villani's Nuova Cronica in the Vatican Library (ms. Chigiano L VIII 296 - Biblioteca Vaticana) |

||

| 'In the year of Christ 1215, M. Gherardo Orlandi being Podestà in Florence, one M. Bondelmonte dei Bondelmonti, a noble citizen of Florence, had promised to take to wife a maiden of the house of the Par. xvi. 136-144. Amidei, honourable and noble citizens; and afterwards as the said M. Bondelmonte, who was very charming and a good horseman, was riding through the city, a lady of the house of the Donati called to him, reproaching him as to the lady to whom he was betrothed, that she was not beautiful or worthy of him, and saying: "I have kept this my daughter for you;" whom she showed to him, and she was most beautiful; and immediately by the inspiration of the devil he was so taken by her, that he was betrothed and wedded to her, for which thing the kinsfolk of the first betrothed lady, being assembled together, and grieving over the shame which M.-122- Bondelmonte had done to them, were filled with the accursed indignation, whereby the city of Florence was destroyed and divided. For many houses of the nobles swore together to bring shame upon the said M. Bondelmonte, in revenge for these wrongs. And being in council among themselves, after what fashion they should punish him, whether by beating or killing, Mosca de' Lamberti said the Inf. xxviii. 103-111. Par. xvi. 136-138. evil word: 'Thing done has an end'; to wit, that he should be slain; and so it was done; for on the morning of Easter of the Resurrection the Amidei of San Stefano assembled in their house, and the said M. Bondelmonte coming from Oltrarno, nobly arrayed in new white apparel, and upon a white palfrey, arriving at the foot of the Ponte Vecchio on Par. xvi. 145-147. this side, just at the foot of the pillar where was the statue of Mars, the said M. Bondelmonte was dragged from his horse by Schiatta degli Uberti, and by Mosca Lamberti and Lambertuccio degli Amidei assaulted and smitten, and by Oderigo Fifanti his veins were opened and he was brought to his end; and there was with them one of the counts of Gangalandi. For the which thing the city rose in arms and Cf. Par. xvi. 128. tumult; and this death of M. Bondelmonte was the cause and beginning of the accursed parties of Guelfs and Ghibellines in Florence, albeit long before there were factions among the noble citizens and the said parties existed by reason of the strifes and questions between the Church and the Empire; but by reason of the death of the said M. Bondelmonte all the families of the nobles and the other citizens of Florence were divided, and some held with the Bondelmonti, who took the side of the Guelfs, and were its leaders, and some with the Uberti, who were the leaders of the Ghi-123-bellines, whence followed much evil and disaster to our city, as hereafter shall be told; and it is believed that it will never have an end, if God do not cut it short. And surely it shows that the enemy of the human race, for the sins of the Florentines, had power in that idol of Mars, which the pagan Florentines of old were wont to worship, that at the foot of his statue such a murder was committed, whence so much evil followed to the city of Florence. The accursed names of the Guelf and Ghibelline parties are said to have arisen first in Germany by reason that two great barons of that country were at war together, and had each a strong castle the one over against the other, and the one had the name of Guelf, and the other of Ghibelline, and the war lasted so long, that all the Germans were divided, and one held to one side, and the other to the other; and the strife even came as far as to the court of Rome, and all the court took part in it, and the one side was called that of Guelf, and the other that of Ghibelline; and so the said names continued in Italy.'[a] Villani's Nuova Cronica | The Ponte Vecchio and the Buondelmonte murder |

||

|

||

Peter III of Aragon's fleet landing at Trapani |

||

|

||

Peter III of Aragon's fleet landing at Trapani. Notice the king wearing the crown and directing the landing, Biblioteca Apostòlica Vaticana |

||

He ordered his fleet to sail for Sicily, landed at Trapani on August 30, 1282. |

||

|

||

Pietro III riceve due monaci inviati dal papa durante la conquista della Sicilia |

||

|

||

Pietro III riceve due monaci inviati dal papa durante la conquista della Sicilia, Biblioteca Apostòlica Vaticana |

||

|

||

Peter III of Aragon receives the ambassadors of the Emperor Frederick II of Sicily and the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII |

||

|

||

Peter III of Aragon receives the ambassadors of the Emperor Frederick II of Sicily and the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII to convince the king to intervene in the war against Charles of Anjou. |

||

The Battle of Montaperti, 1260 |

||

| In his Cronica, Villani writes that the Guelph defeat by the Ghibellines at Montaperti in 1260 was a major setback to the historical progress of the Republic of Florence.[14] In this civil war, the Guelphs were a faction united with the papacy in Rome, while the Ghibellines were allied with the descendants of Emperor Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire and supported by Siena.[14] According to Villani, the Florentine Guelphs' last stand was in defending the Carroccio, a chariot which symbolized the independence of the Commune of Florence.[14] Villani estimated that 2,500 Florentine troops were killed and 1,500 captured during the battle, which Roberta J.M. Olson states are conservative numbers in regards to subsequent historians writing of the battle's casualties.[14] |

||

|

||

The Battle of Montaperti from an illustrated manuscript of Giovanni Villani's Nuova Cronica in the Vatican Library (ms. Chigiano L VIII 296 - Biblioteca Vaticana) |

||

How the Florentines raised an army to fortify Montalcino, and were discomfited by Count Giordano and by the Sienese at Montaperti |

||

'The people of Florence having taken the ill resolve to raise an army, craved assistance from their friends, which came with foot soldiers and with horse, from Lucca, and Bologna, and Pistoia, and Prato, and Volterra, and Samminiato, and Sangimignano, and from Colle di Valdelsa, which were in league with the commonwealth and people of Florence; and in Florence there were 800 horsemen of the citizens and more than 500 mercenaries. And the said people being assembled in Florence, the host set forth in the end of August, and for pomp and display they led out the carroccio, and a bell, which they called Martinella, on a car with a wooden tower on wheels, and there went out nearly all the people with the banners of the guilds, and there did not remain a house or a family in Florence which went not forth on foot or on horseback, at least one for each house, and for some two or more, according to their power. And when they found themselves in the territory of Siena, at the place agreed upon, on the river Arbia, at the place called Montaperti, with the men of Perugia and of Orvieto, which there joined with the Florentines, there were gathered together more than 3,000 horse and more than 30,000 foot. And whilst the host of the Florentines was thus preparing, the aforesaid framers of the plot, which were in Siena, in order that it might be the more fully accomplished, sent to Florence certain other friars to hatch treason with certain Ghibelline magnates and popolani which had not been exiled from Florence, and would therefore have to join the general muster of the army. With these, then, they plotted that when they were drawn up for battle, they should from divers quarters flee from their companies, and repair to their own party, to confound the Florentine army. And this plot they made because they seemed to themselves to be but few in comparison with the Florentines; and so it was done. |

||

|

||

Florence Cathedral, 1296 |

||

Villani describes the rebuilding of Florence after the 1293 rebellion of one Giano della Bella; he notes that by 1296 conditions were once again in a "tranquil state".[2] He states that the citizens of Florence were discontented with the small stature of their cathedral, one that did not fit the greatness of their city, and so agreed in 1296 to expand and renew the building.[2] A new foundation was laid in September of that year, adding new marble and sculptural figures.[2] Villani mentions the cardinal legate sent by the Pope in Rome who laid the first stone of the foundation,[2] a significant event since it was the first papal legate to visit Florence. Villani relates that for the construction of the church, it was required of the Commune of Florence that a subsidy of four denari on each libra be paid out of the city treasury in addition to a head-tax of two soldi for each adult male.[15] On July 18, 1334, work began on the new campanile (bell tower) of the cathedral, the first stone placed by the bishop of Florence in front of an audience of clergy, priors, and other magistrates.[15] Villani notes that the commune chose "our fellow-citizen Giotto" as the designer of the tower, a man who was "the most sovereign master of painting in his time".[15] |

||

|

||

Palazzo Vecchio, 1299 |

||

According to Villani, in 1299, the commune and people of Florence laid the foundation for the Palazzo Vecchio, to replace the town hall that was located in a house behind the church of San Brocolo.[15] The new Palazzo Vecchio was to serve as a protective municipal palace for the priors and magistrates, shielding them from the factional strife of the Guelphs and Ghibellines as well as the brawls between the people and magnates over the renewal of the priors every two months.[15] The Uberti family houses had formerly stood at the location of the new piazza, but the Uberti were "rebels of Florence and Ghibellines" and thus the plaza was intentionally laid upon the former location of their homes so they could never be rebuilt.[15] According to Villani, the Uberti family was not even allowed to return to Florence.[16] In planning for the large expanse of the plaza, the commune of Florence purchased the homes of citizens such as the Foraboschi family, so that they could be demolished to make room for construction.[15] In fact, the main tower of the Palazzo was built upon a previously existing tower of the Foraboschi family known as "La Vacca" or "The Cow".[15] |

||

|

||

Trend of building country homes, early 14th century |

||

Villani boasts of Florence's pristine architecture in its monasteries and churches, as well as its ornate houses and beautiful palaces.[17] His opinion is clear even in the title of the chapter he devotes to this topic, "More on the greatness and status and magnificence of the city of Florence".[17] However, Villani is quick to add that those who spent too much on the lavish excesses of continuous remodelling and refurnishing of homes were sinners and could be "considered crazy because of their extravagant spending".[18] Villani also describes the growing trend in the early 14th century of affluent Florentine citizens building large country homes far outside the walls of Florence, in the hills of Tuscany.[19] |

||

|

||

Works sponsored by Robert of Naples, 1316 |

||

While holding the signoria of Florence, Robert of Naples (1277–1343) had the eastern part of the Bargello in Florence constructed, where he had his vicar the Count of Battifolle reside.[20] Villani writes in 1316 that Robert's vicar oversaw the construction of a large part of the new palace, which would suggest Robert's vicar had a great amount of influence in the construction of the eastern addition of the Palazzo del Podestà, including its Magdalen Chapel.[20] |

||

|

||

Famine of 1328 |

||

There was a famine in 1328 which not only devastated Florence, but caused the people of Perugia, Siena, Lucca, and Pistoia to turn away any beggars who approached their towns because they could not provide them with food.[20] Villani reports that Florence did not turn away beggars, but cared for anyone who approached the city and was in need of immediate subsistence.[22] According to Villani, the Florentines sought grain from Sicily, having it brought into port at Talamone and transporting all the way to Florence at great expense.[22] Florence also sought aid and food supplies from Romagna and Arezzo.[22] Villani writes of the bread riots of the poor who could not afford a whole staio of wheat with their meager salaries:

Villani states that the commune of Florence spent more than 60,000 gold florins to mitigate this effects of this disaster.[22] In order to save their own funds and calm the rage of the riotous poor, all the baker's ovens in the city were requisitioned by the commune and a loaf of bread weighing 170 g (6 oz) was then sold at a meager four pennies.[22] This price was fixed in consideration that poor workers who made only eight to twelve pennies a day could now buy enough bread to survive.[22] |

||

|

||

Fires of 1331 and 1332 |

||

On June 23, 1331, a fire broke out toward the left bank of the Ponte Vecchio bridge, destroying all twenty shops located on the bridge.[24] Villani notes that this was a heavy loss to local craftsmen of Florence, while two craftsman apprentices died in the fire.[24] On September 12 of that same year a fire broke out at the household of the Soldanieri, killing six people in a house of carpenters and a blacksmith that was located near the church of Santa Trinità.[24] On February 28, 1332, a fire broke out in the palace of the podestà, the leading magistrate of the city.[24] This fire destroyed the roof of the palace and destroyed two-thirds of the entire structure from the ground floor up, prompting the government to rebuild the palatial residence totally out of stone, all the way up to the roof.[24] On July 16 of that year the palace of the wool guild caught fire and everything from the ground floor up was destroyed, prompting the wool guild to reconstruct a new palatial residence on a larger scale and with stone vaults leading up to the roof.[24] |

||

|

||

Flood of 1333 |

||

Villani states that by noon on Thursday, November 4, 1333, a flood along the Arno River spread across the entire plain of San Salvi.[22] He wrote that by nightfall the eastern wall of the city that was damming the water became damaged and then washed away in the flood, allowing the flood waters to breach and fill the city streets.[22] He claims that the water rose above the altar in the Florence Baptistry, reaching over half the height of the porphyry columns.[22] Bartlett notes that these columns, presented to Florence by the Pisans more than two hundred years before, have scratched lines to this day indicating the water level reached by the flood in 1333.[22] Villani further claims that the height of the flood water in the courtyard of the commune's palace (residence of the podestà) reached 3 m (10 ft).[22] The Carraia bridge collapsed with the exception of two of its arches, while the Trinità bridge collapsed except for one pier and one arch located towards the church of the Santa Trinità.[25] The Ponte Vecchio—save the two central piers—was swept away when huge logs in the rushing water became clogged around the it, allowing the water to build and leap over the arches, states Villani.[26] There was an old statue of Mars that stood on a pedestal near the Ponte Vecchio, but this too was taken by the flood along the Arno.[26] |

||

|

||

Black Death of 1348 |

||

Villani describes how the plague of Black Death in 1348 was much more widespread amongst the inhabitants of Pistoia, Prato, Bologna, Romagna, Avignon and the whole of France than it was in Florence and Tuscany.[24] He notes that the Black Death also killed many more in Greece, Turkey (Anatolia), in countries amongst the Tartars and in places "beyond the sea", across the whole Levant and Mesopotamia in the areas of Syria and "Chaldea", as well as the islands of Cyprus, Crete, Rhodes, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Elba, and "from there soon reached all the shores of the mainland".[24] Relating the course of events and the sailors from Genoa who brought the plague to mainland Europe, Villani writes:

Villani was unable to complete this last sentence, since he himself died of the plague while writing the Cronica.[24] |

||

|

||

Municipal statistics |

||

Giovanni Villani recorded many statistics associated with the city of Florence. This included—but certainly wasn't limited to—figures such as 80 banks located in the city, 146 bakeries, 80 members in an association of city judges with 600 notaries, 60 some physicians and surgical doctors, and 100 some shops and dealers of spices.[27] Each week the city consumed 13,200 bushels of grain while the city annually consumed 4,000 oxen and calves, 60,000 mutton and sheep, 20,000 goats, and 30,000 pigs.[27] He wrote that annually, in the month of July, some 4,000 melons were imported through Porta San Friano.[27] Population Villani states that the whole population of Florence—men, women, and children—in reference to the years 1336 to 1338, was estimated to be 90,000 due to the amount of bread needed daily.[28][29] Villani recorded an exact figure of 94,000 residents (which he says was very reliable data that included even the poor) in April 1347, a year before the Black Death.[23] A black bean was deposited for every male child baptized and a white bean deposited for every female child baptized in the Florence Baptistry—from these baptisms the average annual birth rate was figured at 5,500 to 6,000.[28][30]Villani pointed out that the newborn males often outnumbered the newborn females by 300 to 500 on each count.[28][31] He noted that in his day the adult, male citizen population of the city was about 25,000 (those between the age of fifteen and seventy who could bear arms); 1,500 of these were noble and upper class citizens.[28][29] Giovanni Villani stated that at all times there were about 1,500 foreigners, transients, and soldiers in the city.[28] Education Besides population statistics, Villani also offered statistics on education. He wrote that boys and girls learning to read numbered 8,000 to 10,000 each year.[28][31] There were 1,000 to 1,200 children learning to use the abacus and algorism for mathematics.[28][31] In the four large, prestigious schools of Florence, there were always 550 to 600 students in attendance to learn proper grammar and scholastic logic.[28][31] Religious facilities Villani also offered statistics on religious and health facilities. The total number of churches in Florence and its suburbs was 110—including 57 parishes, five abbeys with two priors and 80 monks each, 24 nunneries with some 500 women, 10 orders of friars, and 30 hospitals with over 1,000 beds to offer to the sick and dying.[28] Overall there were 250 to 350 chaplain priests in the city.[28] Commerce and trade Besides religious facilities, Villani also provided information on commerce and trade. He states that there were about 200 workshops overseen by the Arte della Lana (guild of wool merchants and entrepreneurs in the woolen industry) of Florence.[32] He states that these workshops produced some 70,000 to 80,000 pieces of cloth a year, with a total worth of 1,200,000 gold florins.[32] He states that a third of this sum "remained in the land" as a reward for labor, while 30,000 people lived from this sum of money.[27] Giovanni notes that earlier in Florence there were actually 300 workshops producing 100,000 pieces of cloth annually, but these were of coarser quality and lesser value (before the importation and knowledge of English wool).[27] Giovanni noted that the rise of the Florentine wool industry in the 13th century came about with this shift from producing a mass of cheap woolen products to high-margin luxury fabrics produced in limited qualities with high demand.[33] The guild of the Arte di Calimala (importers, refinishers, and sellers of French and Transalpine cloth) annually imported 10,000 pieces of cloth worth 300,000 gold florins; these were sold on the streets of Florence, while a large but unknown amount was exported back out of Florence.[27] There was a large flux of international traders entering Florence, so much so that Villani states all attempts at creating market fairs in the early 14th century failed because "there always is a market in Florence."[34] |

||

|

||

Concerning the poet Dante Alighieri of Florence |

||

In the said year 1321, in the month of July, Dante Alighieri, of Florence, died in the city of Ravenna, in Romagna, having returned from an embassy to Venice in the service of the lords of Polenta, with whom he was living; and in Ravenna, before the door of the chief church, he was buried with great honour, in the garb of a poet and of a great philosopher. He died in exile from the commonwealth of Florence, at the age of about fifty-six years. This Dante was a citizen of an honourable and ancient family in Florence, of the Porta San Piero, and our neighbour; and his exile from Florence was by reason that when M. Charles of Valois, of the House of France, came to Florence in the year 1301 and banished the White party, as has been afore mentioned at its due time, the said Dante was among the chief governors of our city, and pertained to that party, albeit he was a Guelf; and, therefore, for no other fault he was driven out and banished from Florence with the White party; and went to the university at Bologna, and afterwards at Paris, and in many parts of the world. This man was a great scholar in almost every branch of learning, albeit he was a layman; he was a great poet and philosopher, and a perfect rhetorician alike in prose and verse, a very noble orator in public speaking, supreme in rhyme, with the most polished and beautiful style which in our language ever was up to his time and beyond it. In his youth he wrote the book of The New Life, of Love; and afterwards, when he was in exile, he wrote about twenty very excellent odes, treating of moral questions and of love; and he wrote three noble letters among others; one he sent to the government of Florence complaining of his undeserved exile; the second he sent to the Emperor Henry when he was besieging Brescia, reproving him for his delay, almost in a prophetic strain; the third to the Italian cardinals, at the time of the vacancy after the death of Pope Clement, praying them to unite in the election of an Italian Pope; all these in Latin in a lofty style, and with excellent purport and authorities, and much commended by men of wisdom and insight. And he wrote the Comedy, wherein, in polished verse, and with great and subtle questions, moral, natural, astrological, philosophical, and theological, with new and beautiful illustrations, comparisons, and poetry, he dealt and treated in 100 chapters or songs, of the existence and condition of Hell, Purgatory and Paradise as loftily as it were possible to treat of them, as in his said treatise may be seen and understood by whoso has subtle intellect. It is true that he in this Comedy delighted to denounce and to cry out after the manner of poets, perhaps in certain places more than was fitting; but may be his exile was the cause of this. He wrote also The Monarchy, in which he treated of the office of Pope and of Emperor. [And he began a commentary upon fourteen of his afore-named moral odes in the vulgar tongue which, in consequence of his death, is only completed as to three of them; the which commentary, judging by what can be seen of it, was turning out a lofty, beautiful, subtle, and very great work, adorned by lofty style and fine philosophical and astrological reasonings. Also he wrote a little book entitled, De Vulgari Eloquentia, of which he promises to write four books, but of these only two exist, perhaps on account of his untimely death; and here, in strong and ornate Latin and with beautiful reasonings, he reproves all the vernaculars of Italy.] This Dante, because of his knowledge, was somewhat haughty and reserved and disdainful, and after the fashion of a philosopher, careless of graces and not easy in his converse with laymen; but because of the lofty virtues and knowledge and worth of so great a citizen, it seems fitting to confer lasting memory upon him in this our chronicle, although, indeed, his noble works, left to us in writing, are the true testimony to him, and are an honourable report to our city.[a]

|

||

|

||

Domenico di Michelino, Dante and the Three Kingdoms, 1465, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence |

||

Domenico di Michelino (1417–1491) was an Italian painter of the Florentine school and a follower of the style of Fra Angelico. He was born and died in Florence. The artist named himself after his master, a certain Michelino. He had his painterly training under Fra Angelico whose assistant he also became. His style is similar to that of Filippo Lippi and Pesellino. |

||

|

||

References Bartlett, Kenneth R. (1992). The Civilization of the Italian Renaissance. Toronto: D.C. Heath and Company. ISBN 0-669-20900-7 (Paperback).

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

View from Podere Santa Pia

on the coast and Corsica |

||

|

||||

Colle Val d'Elsa |

Siena, duomo |

Pitigliano |

||

Florence, San Miniato al Monte |

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia isoffering offering its guests a breathtaking view over the Maremma hills. On clear days, one can even see Corsica.

|

||||

Giovanni Villani: Florentine chronicle, translation by David Burr | www.fordham.edu Giovanni Villani: La Nuova Cronica | Un'opera emblematica della storiografia trecentesca | www.cli.di.unipi.it |

||||

|

||||

| This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles Nuova Cronica, Amidei, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nuova Cronica - ms. Chigiano L VIII 296 - Biblioteca Vaticana. |

||||