|

| Pietro Perugino, St. Sebastian and pieces of figure of St. Rocco and St. Peter (detail), 1478, Chiesa di Santa Maria Assunta, Cerqueto |

Art in Tuscany | Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian |

| The martyrdom of Saint Sebastian is one of the most enduring themes in Western religious art. The execution scene so often portrayed - with the Saint transfixed with arrows - is based on the legend about his life and death during the reign of the Roman emperor, Diocletian. However, it is the symbolic association of arrows with the Black Death - during the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance - which identifies Sebastian as the patron saint of plague victims. After more than four centuries of recurrent epidemics, the plague died out in Europe; but the image of St Sebastian continued to inspire artists until the end of the 19th century.

|

Saint Sebastian (died c. 288) was a Christian saint and martyr, who is said to have been killed during the Roman emperor Diocletian's persecution of Christians. He is commonly depicted in art and literature tied to a post and shot with arrows. This is the most common artistic depiction of Sebastian; however, he was rescued and healed by Saint Irene of Rome before criticising the emperor and being clubbed to death.[1] He is venerated in the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches. |

||

Life |

||

|

||

| According to Sebastian's 5th-century Acta Sanctorum,[2] still attributed to Ambrose by the 17th-century hagiographer Jean Bolland, and the briefer account in Legenda Aurea, he was a man of Gallia Narbonensis who was taught in Milan and appointed as a captain of the Praetorian Guard under Diocletian and Maximian, who were unaware that he was a Christian. Sebastian was known for having encouraged in their faith two Christian prisoners due for martyrdom, Mark and Marcellian, who were bewailed and entreated by their family to forswear Christ and offer token sacrifice. His presence was said to have cured a woman of her muteness, and that the miracle instantly converted 78 persons. According to tradition, Mark and Marcellian were twin brothers and were deacons. They were from a distinguished family and were both married, living in Rome with their wives and children. The brothers refused to sacrifice to the Roman gods and were arrested. They were visited by their father and mother, Tranquillinus and Martia, in prison, who attempted to persuade them to renounce Christianity. Sebastian ended up converting Tranquillinus and Martia, as well as Saint Tiburtius, the son of Chromatius, the local prefect. Nicostratus, another official, and his wife Zoe were also converted. It has been said that Zoe had been a mute for 6 years. However, she made known to Sebastian her desire to be converted to Christianity. As soon as she had, her speech returned to her. Nicostratus then brought the rest of the prisoners; these 16 persons were also converted by Sebastian.[3] Chromatius and Tiburtius converted; Chromatius set all of his prisoners free from jail, resigned his position, and retired to the country in Campania. Mark and Marcellian, after being concealed by a Christian named Castulus, were later martyred, as were Nicostratus, Zoe, and Tiburtius. Martyrdom Diocletian reproached Sebastian for his supposed betrayal, and he commanded him to be led to the field and there to be bound to a stake to be shot at. "And the archers shot at him till he was as full of arrows as an urchin,"[5] leaving him there for dead. Miraculously, the arrows did not kill him. The widow of Castulus, Irene of Rome, went to retrieve his body to bury it, and found he was still alive. She brought him back to her house and nursed him back to health. The other residents of the house doubted he was a Christian. One of those was a girl who was blind. Sebastian asked her "Do you wish to be with God?", and made the sign of the Cross on her head. "Yes", she replied, and immediately regained her sight. Sebastian then stood on a step and harangued Diocletian as he passed by; the emperor had him beaten to death and his body thrown in a privy. But in an apparition Sebastian told a Christian widow where they might find his body undefiled and bury it "at the catacombs by the apostles." Of the miraculous effect of the example of Sebastian, the Golden Legend reports, Sebastian was also said to be a defense against the plague. The Golden Legend transmits the episode of a great plague that afflicted the Lombards in the time of King Gumburt, which was stopped by the erection of an altar in honor of Sebastian in the Church of Saint Peter in the Province of Pavia. Because Sebastian had been thought to have been killed by the arrows, and yet was not, and then later was killed by the same emperor who had ordered him shot, he is sometimes known as the saint who was martyred twice. |

||

|

||

Saint Sebastian in art and literature |

||

|

||

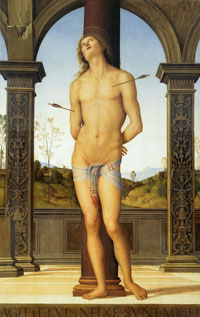

Pietro Perugino, Saint Sebastian, 1495, Louvre, Paris |

||

| The earliest representation of Sebastian is a mosaic in the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo (Ravenna, Italy) dated between 527 and 565. The right lateral wall of the basilica contains large mosaics representing a procession of 26 martyrs, led by Saint Martin and including Sebastian. The martyrs are represented in Byzantine style, lacking any individuality, and have all identical expressions.

Another early representation is in a mosaic[6] in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli (Rome, Italy), probably made in the year 682. It shows a grown, bearded man in court dress but contains no trace of an arrow.[7] The archers and arrows begin to appear by 1000, and ever since have been far more commonly shown than the actual moment of his death by clubbing, so that there is a popular misperception that this is how he died.[8] As protector of potential plague victims (a connection popularized by the Golden Legend[9]) and soldiers, Sebastian naturally occupied a very important place in the popular medieval mind, and hence was among the most frequently depicted of all saints by Late Gothic and Renaissance artists, in the period after the Black Death.[10] The opportunity to show a semi-nude male, often in a contorted pose, also made Sebastian a favourite subject.[11] His shooting with arrows was the subject of the largest engraving by the Master of the Playing Cards in the 1430s, when there were few other current subjects with male nudes other than Christ. Sebastian appears in many other prints and paintings, although this was also due to his popularity with the faithful. Among many others, Botticelli, Perugino, Titian, Pollaiuolo, Giovanni Bellini, Guido Reni (who painted the subject seven times), Mantegna (three times), Hans Memling, Gerrit van Honthorst, Luca Signorelli, El Greco, Honoré Daumier, John Singer Sargent and Louise Bourgeois all painted Saint Sebastians. The saint is ordinarily depicted as a handsome youth pierced by arrows. There were predella scenes, when required, often of his arrest, confrontation with the Emperor, and final beheading. The illustration in the infobox is the Saint Sebastian of Il Sodoma, at the Pitti Palace, Florence. |

||

| A mainly 17th-century subject, though found in predella scenes as early as the 15th century,[12] was St Sebastian tended by St Irene, painted by Georges de La Tour, Trophime Bigot (four times), Jusepe de Ribera,[13] Hendrick ter Brugghen and others. This may have been a deliberate attempt by the Church to get away from the single nude subject, which is already recorded in Vasari as sometimes arousing inappropriate thoughts among female churchgoers.[14] The Baroque artists usually treated it as a nocturnal chiaroscuro scene, illuminated by a single candle, torch or lantern, in the style fashionable in the first half of the 17th century. There exist several cycles depicting the life of Saint Sebastian. Among them, the frescos in the "Basilica di San Sebastiano" of Acireale (Italy) with paintings by Pietro Paolo Vasta. Egon Schiele, an Austrian Expressionist artist, painted a self-portrait as Saint Sebastian in 1915. During Salvador Dalí's "Lorca (Federico García Lorca) Period", he painted Sebastian several times, most notably in his "Neo-Cubist Academy". For reasons unknown, the left vein of Sebastian is always exposed. On 1993 in Berlin a sculpture "Saint Sebastian" was created by sculptor Angela Laich. In 1911, the Italian playwright Gabriele d'Annunzio in conjunction with Claude Debussy produced a mystery play on the subject. The American composer Gian Carlo Menotti composed a ballet score for a Ballets Russes production which was first given in 1944. In his novella Death in Venice, Thomas Mann hails the "Sebastian-Figure" as the supreme emblem of Apollonian beauty, that is, the artistry of differentiated forms, beauty as measured by discipline, proportion, and luminous distinctions. This allusion to Saint Sebastian's suffering, associated with the writerly professionalism of the novella's protagonist, Gustav Aschenbach, provides a model for the "heroism born of weakness", which characterizes poise amidst agonizing torment and plain acceptance of one's fate as, beyond mere patience and passivity, a stylized achievement and artistic triumph. Sebastian's death was depicted in the 1949 film Fabiola, in which he was played by Massimo Girotti. In 1976, the British director Derek Jarman made a film, Sebastiane, which caused controversy in its treatment of the martyr as a homosexual icon. However, as several critics have noted, this has been a subtext of the imagery since the Renaissance.[15] Also in 1976, a figure of Saint Sebastian appeared throughout the American horror film Carrie.[16] In 2007, artist Damien Hirst presented Saint Sebastian, Exquisite Pain from his Natural History series. The piece depicts a cow in formaldehyde, bound in metal cable and shot with arrows.[17] |

Antonello da Messina, St. Sebastian, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden |

|

Pietro Perugino |

||

| Pietro Vannucci, il Perugino was born in Città della Pieve. He almost certainly trained in Florence under Andrea del Verrocchio. He is first documented in Perugia in 1475, when he was paid for what must have been a minor commission in the Palazzo dei Priori. Yet, he emerges as a fully mature artist by 1479, when Pope Sixtus IV commissioned frescoes from him for the Cappella della Concezione of old St Peter’s, Rome (destroyed in 1602). He went on to work in the Sistine Chapel (see below) in ca. 1481-2. Perugino maintained a workshop in Florence from at least 1487 until 1511. He also maintained a workshop in Perugia, probably from ca. 1495. Perugino failed to keep up with the rapid development of artistic taste from ca. 1500, and his reputation in Florence suffered badly when his Polittico dell' Annunziata (1504-7) for SS Annunziata there was badly received. He nevertheless continued to dominate the art scene in Perugia for some twenty years. Giorgio Vasari saw the St John the Baptist Altarpiece (ca 1510) by Perugino on an altar in San Francesco al Prato that was presumably dedicated to St John the Baptist. Although it was listed among works to be sent to the Musei Capitolini, Rome in 1812, it was subsequently decided that it should remain in the church. It entered the gallery in 1863. The panel depicts St John the Baptist standing in a landscape, flanked by SS Francis, Jerome, Sebastian and Antony of Padua. The figure of St Sebastian is curiously dressed and has been adapted, somewhat opportunistically, from a cartoon used in Perugino's frescoes (ca. 1500) in the Collegio di Cambio. The composition, and in particular the figures of SS Francis and Jerome seem to derive from the Madonna di Loreto (1507), which Perugino painted for Santa Maria dei Servi and which is now in the National Gallery, London. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Antonio del Pollaiuolo and Piero del Pollaiuolo, The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (detail), completed 1475, London, National Gallery |

||

Antonio del Pollaiolo was an Italian painter, sculptor, engraver and goldsmith during the Renaissance. He was born in Florence. |

||

|

||

Andrea Mantegna |

||

|

||

Andrea Mantegna, St Sebastian, c. 1480, Musée du Louvre, Paris |

||

| St. Sebastian is the subject of three paintings by the Italian Early Renaissance master Andrea Mantegna. The Paduan artist lived in a period of frequent plagues; Sebastian was considered protector against the plague as having been shot through by arrows, and it was thought that plague spread abroad through the air. Some of the great Renaissance names associated with paintings of St Sebastian include Titian, Tintoretto, del Sarto, Mantegna, and del Castagno (Targat, 1979 5-25). It is significant that the figure of Sebastian was one of the few semi-nude forms permitted in early Christian art. The martyrdom of St Sebastian was a recurring theme in Mantegna's work, favoured because it combined a religious subject with the chance to paint an athletic male nude. In his long stay in Mantua, furthermore, Mantegna resided near the San Sebastiano church dedicated to St. Sebastian. Mantegna was born about 1431 near Vicenza, Italy. When he was about 10 years old he was adopted by Francesco Squarcione, an art teacher in Padua. Mantegna's skill as an artist developed quickly, and at the age of 17 he set up his own workshop, declaring that he would no longer allow Squarcione to profit by exploiting his talent. There was much interest in Padua at that time in collecting and studying Roman antiquities. Mantegna knew many of the scholars and antiquarians who were involved in this work, and his knowledge of the culture of ancient Rome is apparent in his art. Mantegna remained in Padua until 1459, when Ludovico Gonzaga persuaded him to move to Mantua. He worked for the Gonzaga family for the rest of his life. For them Mantegna created some of his greatest paintings. In one famous work, called the Camera degli Sposi (wedding chamber), he painted the walls and ceiling of a small interior room, transforming it into an open-air pavilion. On the ceiling a painted dome opens onto a painted sky, with painted men and women looking down from above. Rooms creating this sort of illusion became very popular in the baroque era of the 1600s It was almost certainly Federico I Gonzaga, Ludovico’s successor, who commissioned the St Sebastian (Paris, Louvre). The picture, painted in the early 1480s, was probably intended as an altarpiece for the Sainte-Chapelle at Aigueperse in the Auvergne (where it hung until the French Revolution), where Chiara Gonzaga, Federico’s daughter, went to live after her marriage in 1481. The idealized figure of the saint is set against a temple fragment painted with a masterly sense of the texture of both carved and broken rock. Mantegna juxtaposed the saint’s real foot with a foot fragment of a statue, playing on the paragone theme in a demonstration of the versatility of painting. The landscape background is close to that in the Meeting Scene in the Camera Picta, confirming the works’ chronological proximity. Francesco Gonzaga, Federico’s successor, was also appreciative of Mantegna’s abilities, making him a grant of land in 1492 in recognition of his painted works for the family. 'Vasari was to write that Mantegna "always maintained that the good antique statues were more perfect and beautiful than anything in Nature. He believed that the masters of antiquity had combined in one figure the perfections which are rarely found together in one individual and had thus produced single figures of surpassing beauty." Whether or not Mantegna ever made such an uncompromising statement of faith in idealization, these words are relevant to his St Sebastian. The young saint's body looks as if it had been carved out of some unusually hard and flawless marble. It is placed against a Corinthian column (with a glancing illusion to Vitruvius's equation between architectural and bodily proportions). Yet in this, as in many other fifteenth-century religious pictures, the pagan world is shown symbolically in ruins. Fragments of statues and reliefs lie on the ground, the building (based on the arch of Septimius Severus in Rome) is fissured and broken. The apparent contradiction is, however, essential to the meaning of the painting - Christianity, personified by the saint, prevails over all human ills and disasters. St Sebastian was a patron of the sick and his intercession was evoked especially in times of plague, of which there were outbreaks (probably bubonic) every 15 years or so in Venice throughout the century.' [18] |

||

In the San Luca Altarpiece, also known as the San Luca Polyptych, is a polyptych panel featuring 12 figures each in his or her own arch. The seven figures in the top row flank the central figure of Jesus Christ (among them Saint Sebastian). The five beneath flank Saint Luke.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

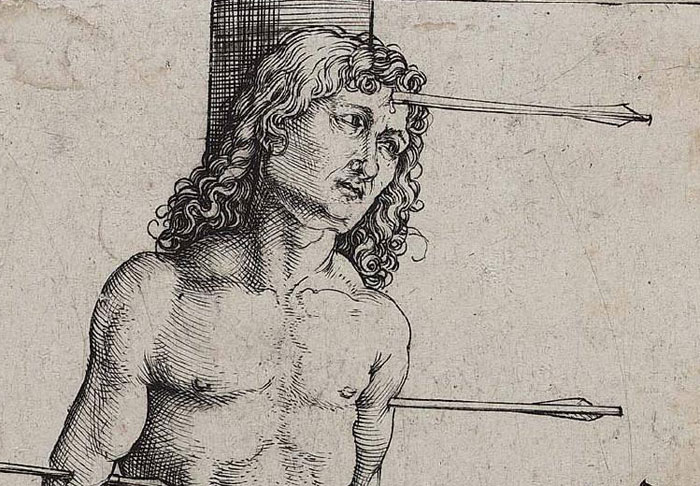

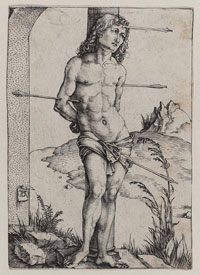

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Saint Sebastian bound to a Column, engraving, circa 1499, on laid paper |

||

Saint Sebastian at the Column is a 1500 engraving by the German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), part of his series of the Lives of the Saints. Italian Inspiration |

Albrecht Dürer, Saint Sebastian at the Column |

|

| [1] Patronage | In the Roman Catholic Church, Sebastian is commemorated by an optional memorial on 20 January. In the Church of Greece, Sebastian's feast day is on 18 December. As a protector from the bubonic plague, Sebastian was formerly one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. The connection of the martyr shot with arrows with the plague is not an intuitive one, however. In Greco-Roman myth, Apollo, the archer god is the deliverer of pestilence; the figure of Sebastian Christianizes this folkloric association. The chronicler Paul the Deacon relates that, in 680, Rome was freed from a raging pestilence by him. Sebastian, like Saint George, was one of a class of military martyrs and soldier saints of the Early Christian Church whose cults originated in the 4th century and culminated at the end of the Middle Ages, in the 14th and 15th centuries both in the East and the West. Details of their martyrologies may provoke some skepticism among modern readers, but certain consistent patterns emerge that are revealing of Christian attitudes. Such a saint was an athleta Christi and a "guardian of the heavens". In Roman Catholicism, Sebastian is the patron saint of athletes as well as the patron saint of archers. Sebastian is the patron and protector saint of the city of Qormi in Malta and the patron saint of Caserta, Petilia Policastro in Italy, Melilli in Sicily, San Sebastián as well as Palma de Mallorca in Spain. He also is the patron saint of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Informally, in the tradition of the Afro-Brazilian syncretic religion Umbanda, Sebastian is often associated with Oxossi, especially in the state of Rio de Janeiro itself. He is also the patron of a college named for him in Manila, which is adjacent to the Parish of San Sebastian. Sebastian is the patron saint of the Diocese of Bacolod, Negros Occidental, Philippines. In his 1906 Reminiscences, Carl Schurz recalls the annual "bird shoot" pageant of the Rhenish town of Liblar which was sponsored by the Saint Sebastian Society, a club of sharpshooters and their sponsors to which nearly every adult member of town belonged.[18] |

||||

| [18] Hugh Honour and John Fleming: A World History of Art, pp. 342-43 [19] Albrecht Dürer | Insight | Christie's | www.christies.com/ 'Before Dürer, prints (mostly woodcuts) were rather crude in design and execution. Essentially they were meant to be religious talismans, protecting the owner from misfortune, rather than works of art as we would understand it. Dürer completely re-imagined what the technique was capable of. He created large complex images, full of life and movement, and set them within realistic settings. He was a revolutionary in commercial terms too. You could say that he made his living as an artist in a way that we recognise today. Before him artists, or artisans, worked mainly on commission. Dürer was much more proactive, creating works of art which he thought would appeal to buyers rather than simply executing someone else’s orders. Because of this he was able to retain possession of his printing plates, which gave him control over the size and quality of the editions. I think his monogram can be seen as one of the first logos, recognisable to everyone, educated and uneducated alike. Dürer dominated not one but two printmaking techniques. He learnt the art of engraving from his father, a successful German goldsmith. It required great technical skill, using a scalpellike tool called a burin to incise lines into a polished metal surface, usually copper, which was soft and easy to work. Ink was applied with a roller, the plate wiped clean and the image printed onto the paper. The second technique was the woodcut, which involved Dürer drawing the design onto the surface of a wooden block. The background would be cut away with a sharp knife or chisel, leaving the design standing proud. Whilst it is unlikely that he cut the blocks himself he knew exactly how it would print and could give precise instructions to the printers.' |

||||

|

||||

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles Saint Sebastian, St. Sebastian (Mantegna), Saint Sebastian at the Column (Dürer), published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden |

The Maremma and Montecristo |

||

Villa La Pietra, near Florence |

Santa Croce, Firenze |

San Miniato al Monte, Florence |

||

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Florence, Duomo |

||

Andrea Mantegna, St Sebastian, (detail),

Andrea Mantegna, St Sebastian, (detail),