|

|

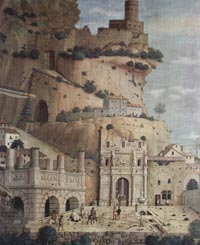

Andrea Mantegna, St Sebastian, c. 1480, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Detail, depicting one of the archers |

|

Andrea Mantegna, Saint Sebastian |

The martyrdom of Saint Sebastian is one of the most enduring themes in Western religious art. Saint Sebastian (died c. 288) was a Christian saint and martyr, who is said to have been killed during the Roman emperor Maximian's persecution of Christians. He is commonly depicted in art and literature tied to a post and shot with arrows. The execution scene so often portrayed - with the Saint transfixed with arrows - is based on the legend about his life and death during the reign of the Roman emperor, Diocletian. However, it is the symbolic association of arrows with the Black Death - during the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance - which identifies Sebastian as the patron saint of plague victims. After more than four centuries of recurrent epidemics, the plague died out in Europe; but the image of St Sebastian continued to inspire artists until the end of the 19th century. |

The St. Sebastian of Vienna |

||

It has been suggested that the picture was made after Mantegna had recovered from the plague in Padua (1456–1457). Probably commissioned by the city's podestà to celebrate the end of the pestilence, it was finished before the artist left the city for Mantua.

According to Battisti, the theme refers to the Book of Revelation. A rider is present in the clouds at the upper left corner. As specified in John's work, the cloud is white and the rider has a scythe, which he is using to cut the cloud. The rider has been interpreted as Saturn, the Roman-Greek god: in ancient times Saturn was identified with the Time that passed by and all left destroyed behind him. Characteristic of Mantegna is the clarity of the surface, the precision of an "archaeological" reproduction of the architectonical details, and the elegance of the martyr's posture. The vertical inscription at the right side of the saint is the signature of Mantegna in Greek.

|

||

| Upper left corner of the painting conceals a horseman in the shape of the cloud. Mantegna used the same trick again in his Triumph of Virtue (1502).

|

||

|

The St. Sebastian of the Louvre |

||

|

||

Andrea Mantegna, St Sebastian, c. 1480, Musée du Louvre, Paris |

||

The Saint Sebastian is part of the High Altar of San Zeno in Verona. Painted in dull colours, with the exception of the touches of red and yellow of the archers, shows the love of the painter for antique ruins and the precision of his careful study of the human body. Nothing is known about the circumstances of the commission and the initial destination of the imposing Saint Sebastian, acquired by the Louvre in 1910. It probably arrived at Aigueperse, in Auvergne, in the early years of 1480 on the occasion of the marriage, in 1481, of Gilbert de Bourbon-Montpensier (governor 1486-1496) and Chiara Gonzaga, daughter of Marquis Federico, perhaps as part of the exorbitant dowry given by her father. Nothing proves that it was painted for this precise event. In the 17th century it was described in praiseworthy terms in the Sainte-Chapelle, but the name of the artist was already forgotten. Before leaving Mantua, Mantegna’s Saint Sebastian seems to have impressed Bernardino da Parenzo who transposed the composition and the décor of antique ruins onto his small panel. It was rather in Auvergne that it was perhaps admired by Antonio Maineri, a painter active in Bologna, who left, if one can believe the documents, to rejoin Gilbert de Bourbon in 1481. The commission in 1490 of a Nativity from Benedetto Ghirlandaio—who we know was absent, in France—illustrates well the Italianizing taste at the court of Auvergne. However, this pleasant painting, of an anecdotal inspiration, is at the antipodes of the monumentality, of the antique vein and the theatrical effects of Mantegna’s Saint Sebastian.[3] The picture was formerly in the church at Aigueperse in Auvergne. It was taken there after being offered in 1481 as a wedding gift to the daughter of Mantegna’s patron, Federico Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, and Gilbert de Bourbon, Count of Montpensier. The painting reflects Mantegna’s fascination for antiquity and illustrates his skill in perspective effects: the monumentality of the body of the martyred saint is heightened by the viewer’s upward-looking viewpoint. Work of religious devotion Obsession with detail The art of trompe l'oeil

|

||

| Detail of the antique city in the background of the Louvre St. Sebastian. The classical ruins are typical of Mantegna's pictures. The cliffy path, the gravel and the caves are references to the difficulties of reaching the Celestial Jerusalem, the fortified city depicted on the top of the mountain, at the upper right corner of the picture, and described in Chapter 21 of John's Book of Revelation. |

||

The St. Sebastian of Venice |

||

The third St. Sebastian by Mantegna was painted some years later (c. 1490), and quite different from the previous compositions, shows a marked pessimism. The grandiose, tortured figure of the saint is depicted before a neutral, shallow background in brown colour. The artist's intentions for the work are explained by a banderol spiralling around an extinguished candle, in the lower right corner. Here, in Latin, it is written: Nihil nisi divinum stabile est. Caetera fumus ("Nothing is stable if not divine. The rest is smoke"). The inscription may have been necessary because the theme of life's fleetingness was not usually associated with pictures of Sebastian. The "M" letter formed by the crossing arrows over the saint's legs could stand for Morte ("Death") or Mantegna.

In this version the imposing figure of the saint, with its almost sculptural outline, emerges with dramatic sharpness from the dark background. This extraordinarily dramatic work was painted for the bishop of Mantua Ludovico Gonzaga and was still in the artist's studio when he died. [4] |

||

Saint Sebastian in the Louvre Museum | www.louvre.fr Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists | Andrea Mantegna Giorgio Vasari | Le vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri | Andrea Mantegna [1] Andrea Mantegna was one of the foremost north italian painters during the Renaissance period He mastered the perspective of foreshortening and made important contributions to the techniques of Renaissance painting. Mantegna became an apprentice and developed strong interests in classica antiquity. The influence of both ancient Rome and contemporary sculptors are highly evident in Mantegna's human figures. Mantegna's greatest successes were a series of frescose on the lives of St. James and St. Christopher in the Ovetari Chapel of the Church of the Eremitani. Mantegna went to Mantua shortly after to become a court painter and soon converted from religious to secular and allgorical subjects. In his master pieces, he displayed illusionistic art in new perspectives and with new limits. Mantegna had a sectacular way of carrying his figured out from the surface and making them realistic. [2] The martyrdom of St Sebastian Saint Sebastian (died c. 288) was a Christian saint and martyr, who is said to have been killed during the Roman emperor Diocletian's persecution of Christians. He is commonly depicted in art and literature tied to a post and shot with arrows. This is the most common artistic depiction of Sebastian; however, he was rescued and healed by Saint Irene of Rome before haranguing the emperor and being clubbed to death; his body was afterwards thrown into the sewer. The earliest representation of Sebastian is a mosaic in the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo (Ravenna, Italy) dated between 527 and 565. Another early representation is in a mosaic in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli (Rome, Italy), which was probably made in the year 682. It shows a grown, bearded man in court dress but contains no trace of an arrow. As protector of potential plague victims (a connection popularized by the Golden Legend[8]) and soldiers, Sebastian naturally occupied a very important place in the popular medieval mind, and hence was among the most frequently depicted of all saints by Late Gothic and Renaissance artists, in the period after the Black Death.[9] The opportunity to show a semi-nude male, often in a contorted pose, also made Sebastian a favourite subject. His shooting with arrows was the subject of the largest engraving by the Master of the Playing Cards in the 1430s, when there were few other current subjects with male nudes other than Christ. Sebastian appears in many other prints and paintings, although this was also due to his popularity with the faithful. Among many others, Botticelli, Perugino, Titian, Pollaiuolo, Giovanni Bellini, Guido Reni (who painted the subject seven times), Mantegna (three times), Hans Memling, Gerrit van Honthorst, Luca Signorelli, El Greco, Honoré Daumier, John Singer Sargent and Louise Bourgeois all painted Saint Sebastians. The saint is ordinarily depicted as a handsome youth pierced by arrows. There were predella scenes, when required, often of his arrest, confrontation with the Emperor, and final beheading. The illustration in the infobox is the Saint Sebastian of Il Sodoma, at the Pitti Palace, Florence. [3] Little is known about the circumstances of the commission and the initial destination of the imposing Saint Sebastian, acquired by the Louvre in 1910. It probably arrived at Aigueperse, in Auvergne, in the early years of 1480 on the occasion of the marriage, in 1481, of Gilbert de Bourbon-Montpensier (governor 1486-1496) and Chiara Gonzaga, daughter of Marquis Federico, perhaps as part of the exorbitant dowry given by her father. Nothing proves that it was painted for this precise event. In the 17th century it was described in praiseworthy terms in the Sainte-Chapelle, but the name of the artist was already forgotten. Around the Aigueperse Saint Sebastian | www.mini-site.louvre.fr [4] The palazzo has lost much of its original substance. It was built from 1421 on in commission of Marino Contarini, son of a procurator. A predecessor building, the palazzo Zeno, which Contarini got as a dowry from his wife Sora Zeno, was pulled down. Note that some inferior sources misleadingly mention a "Doro" family having erected the palace. The name Ca'd'Oro - house of gold - is derived from the initial gildings on some façade areas. In March 1894, baron Giorgio Franchetti acquired the building. He let restore the stairway and the balconies. The original stairway of the Palazzo Contarini dalla Porta di Ferro clearly served as a model, as the similarity of the foliage-like decorations on the stairs easily proves. Franchetti compiled the rich art collection, which became - together with the entirely restored building - property of the state after his death. Today the palazzo as well as the collection can be admired in the museum. Art in Italy | Galleria Franchetti alla Ca’ d’Oro |

||

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Andrea Mantegna, Saint Sebastian and St. Sebastian (Mantegna) published under the GNU Free Documentation License. | ||

| Sources La Grande Storia dell'Arte - Il Quattrocento, Il Sole 24 Ore, 2005 Kleiner, Frank S. Gardner's Art Through the Ages, 13th Edition, 2008 Manca, Joseph. Andrea Mantegna and the Italian Renaissance, 2006 [1] |

||||

Art in Tuscany | Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects |

||||

|

This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Andrea Mantegna and Portrait of Cardinal Ludovico Trevisan, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

Holiday homes in the Tuscan Maremma | Podere Santa Pia |

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montcristo |

||

|

||||

Santa Trinita Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Choistro dello Scalzo, Florence |

||

|

||||

| Vasari Corridor, Florence | San Gimignano |

Florence, Duomo |

||