Walking in Tuscany | Florence | Walking in the Bargello Neighbourhood |

Palazzo del Bargello |

||

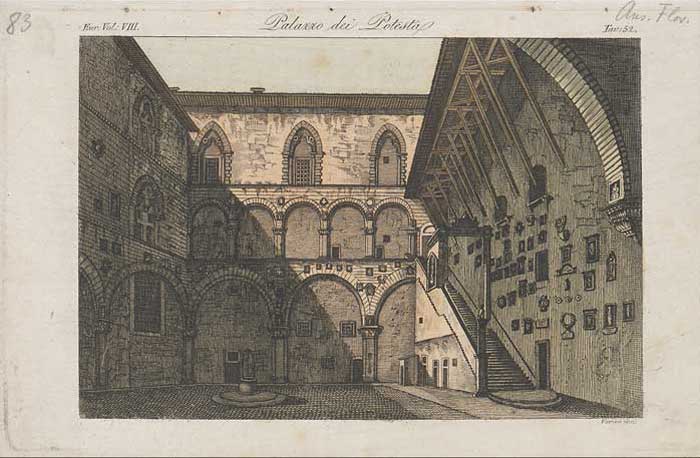

| Built in 1255, the massive and fortresss-like Palazzo del Bargello was the first public building to be erected under the early Republic. It was built for the Capitano del Popolo (the Podesta), who was the chief magistrate of the city. In order to ensure that he was independent, the law insisted that the resident of the post should always be a foreigner. He had to come from a place more than fifty miles away from Florence and his term of office was restricted to one year. The building wasn't called the Palazzo del Bargello until 1574 when it became the residence of the Capitano di Giustizia, the Captain of Police. The name Bargello comes from a slang word for the police. The Torre Volognana, which stands on the corner of the via Ghibellina, also dates back to the 13th century. The bell in the Torre Volognana must be the most under worked in the city, because it only rings once every hundred years to mark the beginning of a new century. (However, an exception was made to this rule when it was rung on November 4th 1966, the day the city suffered its worst ever flood.) The palace is now the Museo Nazionale del Bargello (Entrance fee), home to one of the greatest collections of Renaissance sculpture in the world. The Bargello boasts a large collection of sculptures and artefacts dating back to the 13th century [1]. A Tour of the Rooms: Sala del Verrocchio Sala di Michelangelo Salone del Consiglio The huge courtyard of the old palace is dominated by a beautiful, octagonal well and the walls are decorated with the heraldic crests of the Podesta and other officers of medieval Florence. On the opposite side of the courtyard is a small room with bits and pieces from the 13th and 14th centuries, but the real treasures lie on the first floor. Access to these rooms is via the grand stone staircase that was designed by Neri di Fioravante between 1345 and 1367.The Salone del Consiglio (1340-5) was also designed by Neri da Fioravante. |

||

|

||

Antonio Verico (engraver), Inner courtyard of the Bargello, first half of the 19th century, handcoloured copper engraving, 15.1 x 23.2 cm |

||

| Walking in the Bargello Neighbourhood The tour starts in the Piazza della Signoria, the very heart of Florence. Head towards Palazzo Vecchio, move behind the statue of Hercules and Cacus by Baccio Bandinelli, and walk up the seven or eight steps skirting the façade of the palace itself. If you look closely at the flattish stone almost on the corner of the palace about four courses up, you cannot fail to note the rather roughly carved face of a man. Legend has it that Michelangelo, who frequently crossed this square on his way to and from home, was often importuned by a local lunatic. One day his patience ran out, so while he pretended to listen to the lunatic as he leant against the wall of the palace, he amused himself by carving the man's likeness on the stone behind his back. Ever since that day, this face has been known to Florentines as L'Importuno. Carrying on past the main door to the palace, you will reach the Fountain of Neptune. Head diagonally to your right across Piazza della Signoria, walking past the equestrian statue of Grand Duke Cosimo I by Giambologna; take Via de' Magazzini out of the northeast corner of the square. The street ends in a small square. On the left you can see the façade of the chapel of San Martino dei Buonuomini, containing 15th century frescoes showing the good works performed by the voluntary order whose chapel this was. Incidentally, it takes the place of the earlier church of San Martino in which Dante was married to Gemma Donati, the remains of the facade of the earlier church can be seen in the Canto alla Quarconia, round the back of the present church and just beyond a tavern, the Birreria Centrale, which has set up shop inside the former sacristy! On the right, an archway leads into one of the former cloisters of the Badia Fiorentina, or "Florentine Abbey," affording a marvellous view of the bell tower and of the original façade built by Arnolfo di Cambio, the architect also responsible for the Duomo (Sta. Maria del Fiore) and Palazzo Vecchio. Back in the square, the tower next to the arch, on the corner of Via Dante Alighieri, was Florence's first "town hall", where the city fathers, or priori, met before Palazzo Vecchio was built. Turn right into Via Dante Alighieri, noting Dante's house on your left. 1 - Casa di Dante (Dante's House) |

||

| The Museo - Casa di Dante is located in Via Santa Margherita. At the beginning of the 20th century Giuseppe Castellucci was commissioned to rebuild a 13th century tower house to house a museum to honour Dante Alighieri. Historians expert on medieval times affirm the house sits in the same area of town where Dante was born. The tower house is a four storeyed building. The ground floor houses art exhibitions. The first floor displays documents related to Dante’s childhood and youth, maps, drawings and object to mirror medieval Florence especially the 13th century, when Florence was the capital of Tuscany. The second floor exhibits documents related to his exile lasting till he died in Ravenna 1321. The third floor houses documents related to Dante’s adulthood and copies of paintings depicting the poet and his life. The reproductions belong to original paintings by Giotto, Andrea del Castagno, Beato Angelico, Domenico and Andrea Ghirlandaio, Luca Signorelli and Raffaello. The entrance to the Badia Fiorentina is a little way down on your right. As well as the church itself, you shouldn't miss the small cloister known as the Chiostro degli Aranci. And to the left of the entrance is the church’s greatest masterpiece: the altarpiece showing the Virgin appearing to St Bernard, painted by Filippino Lippi between 1482 and 1486. 2 - Badia Fiorentina On emerging from the Badia, turn left up Via del Proconsolo, remembering to look at the outline on the street paving showing where the foundations of an ancient Roman tower in the city walls were discovered during road works some years ago (the street marks the eastern limit of the Roman colony of Florentia). A little further up the street, you will come to a new building on the corner of Via del Proconsolo and Via Dante Alighieri. When the building was erected, it was decided to leave the remains of the Roman city wall, including a guard tower, on view through a glass floor. The remains can readily be seen by looking through the window from the street. Now cross the street for our next visit. 3 - Palazzo dell'Arte dei Giudici e Notai (Palace of the Judges' and Notaries' Guild) A recent decision to restore the Medieval headquarters of the Judges' and Notaries' Guild prior to its reopening as a restaurant resulted in the discovery of the remains of a fresco cycle containing the earliest known portraits of Dante and Boccaccio. Now backtrack, retracing your steps down Via del Proconsolo, passing between the Badia and the west wall of the Bargello, a stout medieval fortress formerly home to the Capitano del Popolo and now the city's foremost sculpture museum, the Bargello Museum. 4 - Museo del Bargello (Bargello Museum) |

The Badia Fiorentina, with frescoes by Nardo di Cione |

|

| You will need a guidebook for this museum with its extensive sculpture collection, including some of the best work by Donatello, Verrocchio, Michelangelo, Cellini and Giambologna. But there are a few minor things you shouldn't miss either. This building, the official residence of the Captain of the People, later the Podesta` (a kind of mayor) of Medieval Florence, was used also as a prison where many convicts awaiting execution would spend their last days. The Chapel of St. Mary Magdalene, on the first floor, was where they would spend their final hours before beginning their journey to the scaffold, and is remarkable for its frescoes by Giotto and his pupils (mostly his pupils!) containing what was the best known portrait of Dante until the earlier one you've just seen in the Palazzo dell'Arte dei Giudici e Notai was discovered. Also, don't miss the collection of Renaissance medals on the second floor, which includes some wonderful work by Pisanello; or the charming collection of Medieval household implements such as combs, hair pins, mirrors and ivory caskets in the so-called Sala degli Avori, or Ivory Room. On leaving the museum, turn left and walk into the Piazza San Firenze. |

||

The fact that this church was originally built as a grain market in 1290 by Arnolfo Di Cambio -- also responsible for Palazzo Vecchio, the Loggia dei Lanzi and the Cathedral -- but destroyed by fire only 15 years later and subsequently rebuilt between 1337 and 1350, helps to explain its unusual shape. The name goes back to a much earlier 8th c. building, destroyed in 1240, called San Michele in Orto, or St. Michael in the Orchard, because it belonged to a convent with a huge amount of land (including an orchard) in the area. The top two stories were added as grain stores in about 1380, and the ground floor was turned back into a church, its arches being closed in with three-light windows. A good guidebook will take you by the hand and lead you around the outside of the church to admire some of the greatest works of Florentine Renaissance sculpture by such masters as Ghiberti, Donatello, Verrocchio and Giambologna, and then inside to see the masterpiece of Andrea Orcagna in the lower church, officially dedicated to St. Anne. Emerging from the church, you will notice on your right a 14-th c. building with a round-headed and a square door on the ground floor, four small, square windows above them, four large, round-headed windows above that, and finally four more small, square windows on the top floor. This was once the Palazzo dei Capitani di Orsanmichele or Palazzo dell'Arte dei Beccai. 7 - Palazzo dei Capitani di Orsanmichele or Palazzo dell'Arte dei Beccai (Palace of the Captains of Orsanmichele or Palace of the Butchers' Guild) |

||

| Home to the extremely powerful wool merchants' guild in the Middle Ages, which was in fact only suppressed by Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo of Lorraine in 1770. The tabernacle on the corner of the building, known as the Tabernacolo della Tromba, was originally in the old market square (demolished in the late 19th c. to make way for today's Piazza della Repubblica), but it was saved from demolition and re-erected here when the whole palazzo was (perhaps a little too thoroughly) restored in 1905. It was the largest tabernacle in Renaissance Florence, but it took its name from a tiny street known as Vicolo della Tromba (Trumpet Alley) where the corporation stored the municipal trumpets. The palazzo itself was erected in the early 14th c., incorporating a large part of the Medieval tower house known as the Torre de' Compiobbesi. Further alterations (the arch carrying a covered walkway over to Orsanmichele, or the now glazed-in loggia on the south) were carried out in the late 16th c. to designs by Bernardo Buontalenti. It now houses the offices of the Societa` Dantesca Italiana, but it, and its fascinating 14th c. frescoes showing the manufacture of woollen cloth, may be viewed by appointment -- although one of the most interesting of these frescoes, on the ground floor, is now inside a clothes shop round the corner in Via Calimala! Turning back towards the Palazzo dell'Arte dei Beccai, it's worth nipping down Vicolo di Ferro, the tiny alleway alongside it, to see a corner of Florence the 19th c. demolitioners appear to have forgotten! They didn't, of course, and sadly there is only one truly old building here in the Piazza dei Tre Re today. But the feeling of total isolation so close to the heart of Florence is surely unique. Many Florentines don't even know this square exists, never mind the visitors and the tourists! The ancient building before you is the Torre de' Macci. 9 - Torre de' Macci The Macci were an immensely powerful family of the old Florentine nobility in the 13th c., but like most of the old aristocracy, they sided with the Ghibelline, or imperial, party against the Guelph, or papal, party which enjoyed the favour of the rising merchant bourgeoisie. The Ghibelline cause was defeated at the Battle of Benevento in 1260, and the Macci's property was confiscated by the victorious Guelphs, but at least it wasn't demolished. The property of such famous Ghibelline families as the Degli Uberti, for instance, was razed to the ground and an order promulgated that no building was ever to be erected on the site again. The site in question became Piazza della Signoria, so we can't really complain, and in fact archaeologists certainly didn't complain. They were delighted when a plan to repave the square in the 1980's gave them the opportunity to excavate what was, to all intents and purposes, a time capsule. In any event, the Macci's tower remained standing, but this tiny square changed its name from Corte de' Macci (the Macci's Courtyard) to Piazza del Re (King's Square) and then to Piazza dei Tre Re (Three Kings' Square) after a tavern of ill repute that was opened when the area started to "go downhill", and Vicolo dell'Onesta` (Honesty Alley) leading off the square is so called because the offices of the Magistratura dell'Onesta` (Honesty Magistracy) were situated here. These particular magistrates were charged with regulating prostitution in the city, establishing the places where the ladies could practice their trade and the prices they could charge! Returning to the Palazzo dell'Arte dei Beccai, turn right then left into Via Calimala, walking past the facade of the Torre de' Compiobbesi, and head directly south until you come to the Piazza del Mercato Nuovo. 10 - Mercato Nuovo o "Loggia del Porcellino" (New Market, or Straw Market) Built in the mid-16th c. as a market silks and precious stones, from the 19th c. until only very recently it was famous throughout the world as the Straw Market where you could buy the famous Florentine straw hats. Most of the stalls now sell the same leather goods and souvenirs you can find almost everywhere else in the city, but you shouldn't miss Pietro Tacca's famous 17th c. statue of a wild boar, affectionately dubbed the Porcellino, or Little Pig, by the Florentines, located on the south side of the loggia. Rubbing the boar's nose while placing a coin in his mouth is said to bring good luck, but only if the coin then falls and drops between through the grating beneath the statue's snout! Another interesting feature of the market, although it can only be seen when all the stalls have been taken down for the night, is the so-called "Pietra dello Scandalo", or "Stone of Scandal", in the centre of the loggia. This marks the spot where insolvent debtors were brought in Renaissance times, chained, then their hose were pulled down and their buttocks banged repeatedly on the stone circle in punishment. Vicolo della Seta will lead you to the entrance to the: 11 - Palagio di Parte Guelfa (Guelph Party Palace) This was the headquarters of the victorious Guelph Party we discussed earlier. It was built from the 14th c. onwards, and both Brunelleschi and Vasari are known to have worked on it at one time or another. It also once contained frescoes by Giotto and Gherardo Starnina, but sadly both cycles are long gone. Heavily restored in "neo-Medieval" style after the demolition of much of Florence's historic centre in the late 19th c. -- see, for instance, the charming neo-Gothic external staircase -- it contains much that is of interest within it, including works by Donatello (or his school), Luca Della Robbia and Giambologna. It is now the headquarters of the Calcio Storico Fiorentino (Florentine Historic Football association) and of the Corteo Storico della Repubblica Fiorentina (Florentine Republic Historic Cortege). It is also used as an exhibition hall for temporary exhibitions by the local authorities. Not generally open to the public, nevertheless a phone call should get you an appointment to view the inside. The disused church of Santa Maria Sopra Porta, later San Biagio, built alongside the palace, is now a public library, but from its suppression in 1785 until the early 20th c. it was the municipal firemen's barracks. The twin steps leading up to a walled landing outside the door are a rare survival of a type of church entrance that was very common indeed in Medieval Florence, but most of these were demolished along with the historic centre in the late 19th c. The narrow alley across the square, Vicolo del Panico, is fairly representative of what a lot of the demolished centre would have looked like. This, too, was earmarked for demolition, but it was saved after letters of protest written to the London Times caused such a stir in the 1890's that the plan to widen Via Pellicceria right down to the Arno was thankfully never implemented. We now head down the narrowest part of the piazza, which will bring us out onto Via delle Terme. If we turn left, then right onto Por Santa Maria, then first left into Via Vacchereccia, we will be back in Piazza della Signoria. |

|

|

Main squares in Florence |

|

|

View Squares in Florence in a larger map |

[1] Museo del Bargello (Bargello Museum) |

||||

| Salone del Consiglio | This enormous space now houses several masterpieces by the greatest sculptor of the 15th century. I am, of course referring to Donato di Niccolo Betti Bardi, better known to us by his nickname, Donatello. His best-known work, the bronze statue of ‘David’ (c. 1446-60) one of the most enigmatic statues of the entire Renaissance, can be found here. Donatello’s ‘David’ is thought to be the first free-standing, life-sized, nude statue since antiquity. Its fame is largely due, however, to its unconventional and completely unexpected appearance. The Old Testament ‘hero’ is portrayed as a rather effeminate, young boy dressed only in a pair of beautifully tooled, leather boots and pointed hat. His right foot rests on a laurel wreath (a symbol of victory), while his left foot rests on the head of Goliath, whose great sword he casually holds in his right hand. The dreamy mood of the figure is not quite in keeping with the dramatic representation of the biblical story. The body language of the pose reveals less a sense of triumph than one of meditation. Much comment has been made over the link between the erotic nature of the sculpture and Donatello’s own sexual inclinations. Note how one of the wings of the giant’s helmet caresses the inside of the boy’s thigh. The statue made a powerful impression on everyone who saw it. Vasari thought that the work was so lifelike that it must have been made from the cast of a living model. Nothing in the sculptor’s earlier work has prepared us for this image. The room has a number of other works by Donatello including an early marble statue of ‘St George’ (1416), removed from the tabernacle outside the church of Orsanmichele, which has been re-erected against the back wall. St George was the patron saint of the Guild of Armourers and Swordsmiths, who commissioned the work and the statue once sported two of the products of the guild in the form of a metal sword and helmet, both of which have now been lost. We can sense the tension in the flexed body as it is poised for action. Donatello has given the warrior saint a subtle arch of the back which throws the chest and pelvis forward. His left arm rests on his shield while his right tenses with the weight of the weapon it once held. He stands in a position that is normally referred to as ‘at ease’ and yet we feel that he is still ready for action. Vasari was perfectly correct when he said that there was ‘a marvellous sense of movement in the stone’. However, the most remarkable technical innovation of the whole composition is the small marble relief at the base of the statue, which depicts ‘St George slaying the Dragon’. It had been the common practise since the time of ancient Egypt to leave the background of a relief flat and to model the figures against it. Donatello was the first sculptor to pierce the flat marble background and create an illusion of space. Donatello’s genius lay in his ability to make the chisel do almost anything he wanted. In his hands it became more of an instrument for drawing, rather than a tool for carving marble. On the right of the relief, an arcade leads the eye towards the distant hills and trees, while on the left we can see the dragon’s cave set at an angle to the front plane. This type of relief, which Donatello pioneered, is known as rilievo schiacciato, literally, a ‘squashed’ or ‘flattened’ relief’. In the centre of the room there is a portrait bust of ‘Niccolo da Uzzano’ (c. 1430s) in painted terracotta. The bust is a very realistic image of Uzzano, a Florentine banker, patrician and patron of the arts. Donatello depicted the sitter at the ripe old age of sixty, or thereabouts, and his careworn expression reveals the pressure of the passing years. This is literally a ‘warts and all’ representation of Uzzano, which has led many to conclude that the sculptor may have used a face mask to achieve the accuracy of the image. The sculpted portrait bust grew in popularity during the second half of the 15th century and marked the strong influence of humanism and the world of classical antiquity. The busts were inspired by the example of the patricians of Republican Rome and would normally have been placed above the entrance door to a room or house. We will see more examples of the portrait bust, by most of the major sculptors of the 15th century, on the second floor. It is time for us to return to the balcony at the top of the staircase, which acts as an exhibition space for a series of bronze animals by Giambologna. The animals were commissioned, in 1567, for the grotto of the Medici Villa of Castello, on the outskirts of Florence. Freely modelled in wax and clay before being cast in bronze, they are some of the freshest creations of the entire 16th century. Giambologna has managed to evoke the very essence of the different creatures. The most famous animal is perhaps the ‘Turkey’, a bird that was introduced into Europe in the 16th century from the country of the same name. The work is almost impressionistic in its free treatment of form. The modelling of the surface and lack of finish foreshadow the work of a much later age. It has been suggested that Giambologna, in depicting the bird as a ridiculously pompous creature, was gently satirising the contemporary courtier with his formal ruff and heavy robes of office. The design of the ‘Peacock’ is more abstract and stylised. In its strut there is an air of the imperious and the empty headed. The bird throws its head back with a mixture of pomposity and pride. In his depiction of the ‘Eagle’ we can feel all of the menace of this wonderful predator of the skies. The vicious curve of the beak, the angry turn of the head, coupled with the huge claws that encompass the whole mound of earth on which it is perched. |

||||

| Sala del Verrocchio | Andrea del Verrocchio is often remembered, less for his own significant achievements, and more for the fact that he was the master of Leonardo da Vinci. During the second half of the 15th century, he ran one of the most successful workshops in the city and it was there that the young Leonardo learned the elements of his trade. At the time of his death, in 1488, Verrocchio was regarded by many as the leading master of his day and by some as one of the greatest who had ever existed. He was born Andrea di Cione, but adopted the surname of the goldsmith, Giuliano Verrocchio, under whom he had been apprenticed. This was a common practise of the time. In the middle of the room stands Verrocchio’s bronze statue of ‘David’ (1470s), the sculptor’s response to Donatello’s earlier image of the biblical hero. The work was commissioned by Lorenzo the Magnificent, and, in contrast to the nudity of Donatello’s figure, Verrocchio’s ‘David’ is clothed in a short, leather tunic and carries a small dagger rather than a long sword. His mood is pensive rather than triumphant. In the case of the female portrait, there were less references to the classical busts of women. One of the most famous of all was created by Verrocchio and is known as ‘The Lady with a Nosegay’ (14xxx). The portrait is actually more a half-length than bust. This gave the artist the opportunity to express the character and mood of the sitter through the hands as well as the face. In this particular image, the hands are rather more eloquent than the face. Don’t leave the room without looking at Verrocchio’s terrifying depiction of ‘The Resurrection’ (14xxx) in painted terracotta. The design of the work is based on Luca della Robbia’s depiction of the same theme in the cathedral. Verrocchio’s image, however, in its range of expression, is a world away from that of Luca. He has injected a sense of absolute drama into his treatment of the scene. We can feel the terror of the soldier on the left, who has woken to see Christ rising out of the tomb. He turns away with his mouth wide open as he gives vent to a cry of horror. On the right, an older man crouches on the ground, transfixed by what he sees. Two other figures remain asleep, oblivious of what is going on around them. The Sala del Verrocchio also houses the finest collection of portrait busts from the 15th century. There was a revival of this particular genre in the middle of the Quattrocento and demand was particularly high in Florence. The type derives from classical antiquity and its popularity was a product of the humanist spirit of living all’ antica, after the manner of the classical world. On the wall to the right of the entrance you can see the portrait of ‘Piero de’ Medici’ (c.1455-60) by Mino da Fiesole. Piero, the father of Lorenzo the Magnificent, was known as Il Gottoso, the Gouty, an ailment that also afflicted his son. We see him dressed in a delicately carved garment made of brocade. The head is turned away and the alert eyes stare into the distance. This creates an impression of strength and importance, especially when compared with the more natural impression created by Benedetto da Maiano in his nearby portrait of ‘Pietro Mellini’ (1474). The Florentine merchant is dressed in a brocade garment similar to the one worn by Piero de’ Medici. The rounded base and the draped shoulder allies the work more firmly to ancient types. The detailed carving of the face depicts an older man. The raised eyebrows, wrinkled forehead and cheeks suggest a sense of bemusement, which gives life to the image. The high level of detail may point to the use of a plaster mask. |

||||

| Sala di Michelangelo | Here we find the celebrated bust of ‘Michelangelo’, complete with squashed nose, by Daniele da Volterra. (As a young man, Michelangelo received the disfiguring injury to his nose in the Brancacci Chapel after passing a less than favourable judgement on a drawing by a fellow artist, Piero Torrigiani). The middle of the room is dominated by two works by the man himself. The first is a statue of ‘Bacchus’ (1496-7), which Michelangelo carved when he was little more than twenty years old. The second is a bust of ‘Brutus’ (1539), the only bust the sculptor ever carved. The statue of ‘Bacchus’ was commissioned by Cardinal Riario in 1496. Michelangelo finished the work within a year, but the Cardinal was not satisfied with the result and refused to pay for it. Unfortunately, history does not tell is what the cardinal disliked about the work, all we know is that it was bought by the banker, Jacopo Galli, and became part of his collection. It is one of Michelangelo’s early attempts to compete with antique sculpture, but the result is a work in which the pagan and sensual outweigh the noble and heroic. The young god of wine stands uncertainly on the ground, staring vacantly at the cup of wine he is holding. He looks as if he will fall over the moment he starts to walk. Behind him sits a satyr, eating a bunch of grapes, the ultimate source of the god’s inebriation. The coiled satyr acts as a convenient support for the main figure. Michelangelo began work on the bust of ‘Brutus’ almost fifty years later, after he had become a permanent resident in Rome. According to Vasari, the bust was commissioned by Donato Gianotti, another Florentine exile, who had been the Secretary of War in the final Republican government of the city. We should see the commission against a background of political events, which culminated in the assassination of the brutal Alessandro de’ Medici, the first Duke of Florence, in 1537. The bust was a tribute to the Republican spirit in Florence by one of its most ardent patriots. Caesar was seen as the perfect example of tyranny and Brutus, his assassin, as the perfect example of the free spirit of Republicanism. The pose is clearly based on Imperial busts that Michelangelo would have seen in Rome. Brutus turns his head to the left, presenting his right profile to the viewer. It is not known whether the face is based on a real portrait or is purely imaginary. It was finished by his pupil, Tiberio Calcagni, when Michelangelo, for some reason, stopped work on the bust. According to a later epigram that was attached to the base of the bust, Michelangelo stopped work on the piece when he was reminded of the nature of the crime. Cellini’s bust of ‘Cosimo I’ (1545-7) was a product of his rivalry with a fellow sculptor, the pugnaciously competitive, Baccio Bandinelli. Cosimo I was persuaded by Bandinelli to commission, in competition, both Cellini and himself to make busts of the Duke. Cellini produced a remarkable work, which in terms of the intensity of expression, energy of movement and range of fine detail, seemed destined to win. But Cosimo and his court seem to have preferred the less virtuosic work by Bandinelli, which can now be seen at the other end of the room. The bronze statue of ‘Mercury’ (1564-80) is by Giambologna, a Flemish artist called Jean de Boulogne, but more commonly known by the Italian form of his name, who dominated Florentine sculpture throughout the second half of the 16th century. Technical brilliance was Giambologna’s hallmark as a sculptor and this manifests itself in this depiction of Mercury, the messenger of the gods. Giambologna developed a new concept in sculpture, which challenged the powerful influence of classical antiquity. This was the figura serpentinata, a spiral, upward movement through a figure or group which countered the force of gravity. The statue of Mercury is a perfect example of this. We see the god being borne aloft on the breath of the god of wind. All sense of weight seems to have disappeared as Mercury balances on a single, winged foot. The energy of the spiral movement rises up from the base, through the body, and ends in the pointed index finger of the right hand, dissolving all sense of weight. |

|

|||

Art in Tuscany | Florence Piazzas | Le piazze di Firenze Art in Tuscany | Florence | Palazzo del Bargello |

||||

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia article Palazzo del Bargello published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia |

Madonna di Vitaleta Chapel, San Quirico d'Orcia |

||

|

||||

Villa Celsa near Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Choistro dello Scalzo, Florence |

||

| Choosing one of the Florence walking tours you'll be able to visit the world-famous museums of the Uffizi and Accademia Galleries, discovering the main historical and artistic treasures of the city. The tours focus on Florence's major sights and attractions, including the Duomo, the Ponte Vecchio and the city's famous churches and Renaissance palaces. Novelist Henry James called Florence a “rounded pearl of cities -- cheerful, compact, complete -- full of a delicious mixture of beauty and convenience.” The best way to experience the Italian city’s artistry, history and joy of life is by walking the same paths that the Medicis, Michelangelo and James once used. 1 | A Walk Around the Uffizi Gallery 2 | Quarter Duomo and Signoria Square 3 | Around Piazza della Repubblica 5 | San Niccolo Neighbourhood in Oltrarno 6 | Walking in the Bargello Neighbourhood 7 | From Fiesole to Settignano

|

San Miniato al Monte |

|||

The façade and the bell tower of San Marco in Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Florence, Duomo |

||