| |

|

Annunciation is the Christian celebration of the announcement by the angel Gabriel to Mary that she would become the Theotokos (God-bearer). Despite being a virgin, Mary would miraculously conceive a child who would be called the Son of God. Gabriel told Mary to name her son Jesus, meaning "YHWH delivers". Most of Christianity observes this event with the Feast of the Annunciation on 25 March, nine full months before Christmas. According to the Bible (Luke 1:26), the Annunciation occurred in "the sixth month" of Elizabeth's pregnancy with the child who would later become known as John the Baptist.[1]

|

| The Annunciation is one of the most frequent subjects of artistic representation in both the Christian East and as Roman Catholic Marian art, particularly during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and figures in the repertoire of almost all of the great masters. The figures of the Virgin Mary and the Archangel Gabriel, being emblematic of purity and grace, were favorite subjects of Roman Catholic Marian art.

Because the natural composition of the scene–two parallel figures, often elegantly clad–the subject was often employed in the decoration of a diptych or tympaneum (decorated arch above a doorway). In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Annunciation is typically depicted on thea Holy Doors (decorative doorway leading from the nave into the sanctuary).

In Roman Catholic Marian art, scenes depicting the annunciations are also used to represent the dogma of perpetual virginity, via the announcement by the Archangel Gabriel that Mary would conceive a child to be born the prophet of god.

Frescos depicting this scene have appeared in Roman Catholic Marian churches for centuries, and it has been a topic addressed by many artists in multiple media, ranging from stained glass to mosaic, to relief, to sculpture to oil painting.

It has been one of the most frequent subjects of Christian art, particularly during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The figures of the Virgin Mary and the Archangel Gabriel, being emblematic of purity and grace, were favorite subjects of many painters such as Sandro Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Caravaggio, Duccio and Murillo among others. The mosaics of Pietro Cavallini in Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome (1291), the frescos of Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (1303), Domenico Ghirlandaio's fresco at the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence (1486), and Donatello's gilded sculpture at the church of Santa Croce, Florence (1435) are famous examples. |

The crypt of the Siena Cathedral

In 1999, frescoes made around the same time, including an Annunciation closely related to the Princeton panel, were found in the crypt of the Siena Cathedral. The frescoes are exceptionally well preserved and are almost unique in art history. They are a fundamental testimony to the origins and development of the Sienese school and and its main exponents

Painted by artists working Siena in the second half of the 13th century men such as Guido da Siena, Dietisalvi di Speme, Guido di Graziano and Rinaldo da Siena – the cycle of paintings is remarkable for the brightness of the colours covering not only the frescoed walls but also the columns, pilasters, capitals and corbels with geometric or phytomorphic embellishments.

|

|

Sienese painter, active in the last quarter of the 13th century, Annunciazion, 1280 circa, La Cripta del Duomo di Siena [3]

|

Aber wunderbar sind dir/ die Hände benedeit./ So reifen sie bei keiner Frau,/ so schimmernd aus dem Saum: “And yet your hands most wonderfully/ reveal his benison./ From woman’s sleeves none ever grew/ so ripe, so shimmeringly”; these are some words directed to Mary by the archangel Gabriel, in a poem by Rainer Maria Rilke, issued in 1902 and titled Verkündigung: Die Worte des Engels (“Annunciation: Words of the Angel”).

|

|

|

|

| |

|

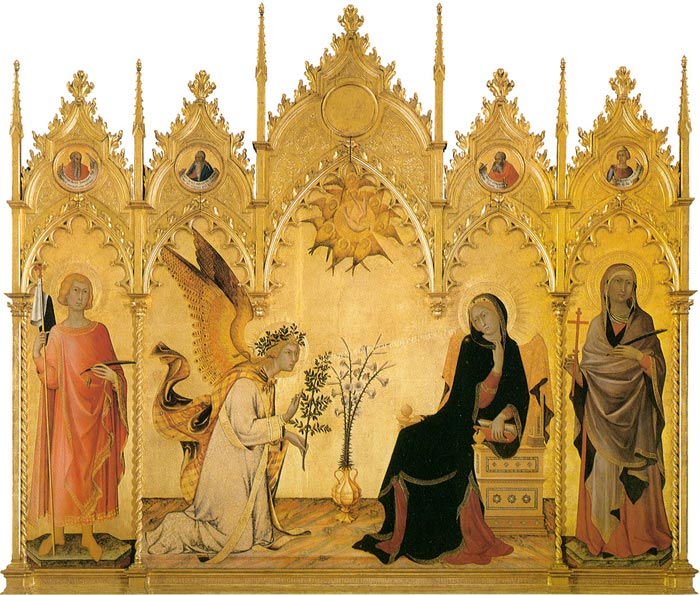

Giotto in Florence and Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti and Simone Martini in Siena were the principal figures in the transformation of Italian painting from a traditional Byzantine mode into a vehicle for the depiction of the varieties of visual and psychological experience. Their impact on Italian art is thus analogous with the roles of Dante and Petrarch in the history of Italian language and literature.

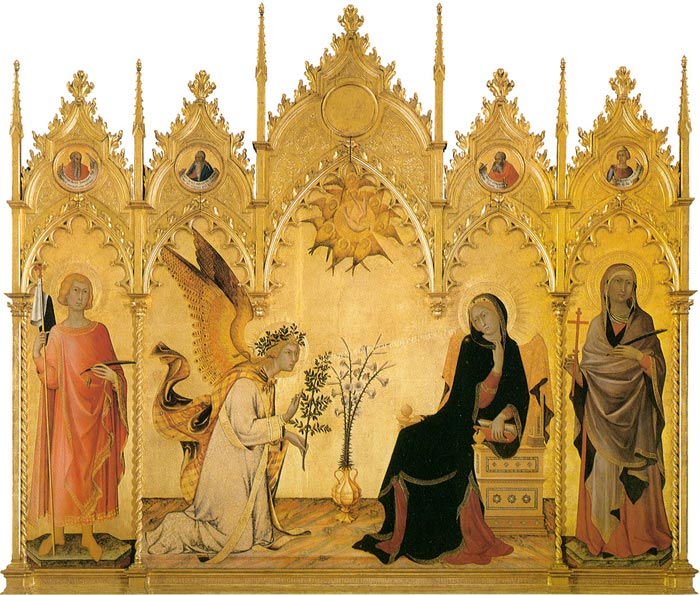

The altarpiece The Annunciation and the Two Saints, now in the Galleria degli Uffizi inFlorence, was executed between 1329 and 1333 for the chapel of Sant'Ansano of the Cathedral in Siena by Simone Martini and his brother-in-law Lippo Memmi, to whom are attributed the two lateral figures: Saint Ansano - patron of Siena - and Saint Giulitta. On the gold background the figures of Angel Gabriel and the Virgin enhances Gothic line, without narrative details: just the central pot with lilies, symbolizing Mary's purity, and the olive branch. The golden relief inscription starting from the Angel's mouth contains beginning words of the Annunciation.

|

|

Simone Martini, Lippo Memmi, The Annunciation and the Two Saints, 1333, tempera on wood, 265 x 305 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

|

A late work in which the precious enamel of the colour and the vibrant undulation of the line are carried to the very highest degree. The two lateral saints, St Ansanus and St Margaret, were painted on Simone's design by his pupil and brother-in-law Lippo Memmi. The inscription on the panel records that Lippo Memmi, whose sister Simone had married in 1324, collaborated on the altarpiece.

In contrast to the concern for time and place in the frescoes, the Annunciation altarpiece emits an atmosphere of sublime unreality. In its elegance of line and rhythm, the exquisitely rendered details of costume, setting, and flower symbols, and the fragile sentiment of the participants in the sacred event, the Annunciationis a supreme masterpiece in the history of lyrical art.

|

|

Annunciation Angel |

|

|

|

|

|

Sant'Ansano e l'arcangelo Gabriele

|

|

La Vergine e Santa Massima, madre di Ansano

|

|

L''arcangelo Gabriele

|

Art in Tuscany | Simone Martini | The Annunciation

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Annunciation, 1344, tempera on wood, 127 x 120 cm Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena

|

The brothers Pietro Lorenzetti (c. 1280–1348) and Ambrogio Lorenzetti (c. 1290–1348) were Sienese painters; they represent two of the most radical and innovative forces in Trecento art. Pietro and Lorenzetti were probably pupils of Duccio, and they both enlarged on the study of narrative and pictorial realism common to Sienese and Florentine art at this time. Their art manifests an interesting admixture of the styles of both schools, combining Sienese sensitivity to color and line with Florentine monumentality.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s last signed and dated work, is from 1344: an Annunciation (Siena, Pinacoteca) painted for the chamber of the tax magistrate in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. The moment of incarnation depicted here presents an interpretation of great theological subtlety, and the spatial construction of the panel shows the tile floor converging to a single vanishing point; this is the closest any Trecento painting comes to true one-point perspective.

It is not known who Ambrogio's teacher was, but his early works indicate that he early received his main inspiration from the art of Duccio, his brother Pietro Lorenzetti, and Giotto. Already his representations reveal a realistic individualism and an intense preoccupation with significant composition and form. These characteristics are most evident in the Allegoriesand Effects of Good and Bad Government in the Palazzo Pubblico, the most important Sienese fresco decoration. In it Ambrogio is seen as an acute observer, an empirical explorer of linear and aerial perspective, a student of classical works of art, and a political and moral philosopher. His desire to depict spatial depth convincingly led him to an increasingly accurate rendering of space in his paintings and almost to one-point perspective in his last work, the Annunciation.

The chapel of Monte Siepi in the rural abbey of San Galgano near Siena was built to honor this Sienese saint and to commemorate a vision of the Madonna that Galgano had on this site. The surviving frescoes are fragmentary; but Ambrogio’s original program for the chapel, c. 1336, included a depiction of Galgano’s vision, portraying a procession of saints and angels on the side walls converging, along with the visitors inside the chapel, toward the Madonna enthroned as queen of heaven on the wall behind the altar. By portraying saints on the walls flanking the enthroned Madonna, Ambrogio involved the entire space of the chapel, surrounding the viewer with Galgano’s vision—a bold experiment that anticipates the carefully coordinated chapel interiors of the seventeenth century. The complex iconographic program for the wall portrayed the Virgin’s central role in the mystery of human redemption: she was shown both as the exalted queen of heaven at the top of the fresco and as the humble Virgin Annunciate at the bottom. As the discovery (in 1996) of the sinopie underlying the frescoes revealed, Ambrogio originally portrayed the Virgin of the annunciation cowering in utter terror before the angel, while the Maestà above showed her enthroned without the child, wearing a crown, and bearing worldly symbols of power—the orb and scepter—in her hands. Both of these unique images were suppressed shortly after completion of the frescoes: the trembling annunciate was painted over by another artist, who replaced her with a typical meekly accepting Madonna; and the empress was transformed into the more usual image of motherhood by placing the Christ child on her lap. Presumably, the patrons had been disturbed by Ambrogio’s provocative interpretations and had subsequently commissioned something more conventional.

|

|

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Annunciazione, 1334-1336, affresco, cappella di San Galgano a Montesiepi

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Annunciation, Oratory of St. Galgano at Montesiepi

|

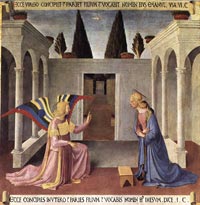

Fra Angelico | The Cortona Altarpiece (The Annunciation), 1433-34

|

The Cortona Altarpiece, the Annunciation, was executed for the church San Domenico at Cortona. Undoubtedly Angelico's first truly great painting, this Annunciation formed a prototype for a noble line of derivatives. The painting repeats the design of the main panel of the Prado altarpiece in a more elaborate architectural setting.

In a loggia of columns and arches, the angel appears to Mary. Shown in profile, he occupies the larger part of the painting, his richly painted wings extending out through the colonnade, their upper tips marking the centre of the picture. He declaims to the Virgin, 'the Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the highest shall overshadow thee' (Luke 1, v. 35). She, demure, with a dove fluttering above her head in a burst of golden light, inclines towards him and responds, 'Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word' (Luke 1, v. 38). Beyond them the picture space extends into the Virgin's chamber, and further, hidden space is hinted at by the bed curtain there which serves also to set off Gabriel's nimbus.

Outside the loggia is a delicately painted garden, enclosed by a palisade, symbolic of Mary's virginity. Carved in a roundel above the centre column is a half-length effigy of Isaiah, who had prophesied the birth of a child to a virgin. The pink entablature of the loggia points to the second reference to the Old Testament, in the top left corner, where Adam and Eve are expelled from Paradise.

The small scenes Fra Angelico painted in translucent colors for the predella (base) of the Cortona Annunciation are each in themselves small hymns of praise to the Virgin. A small section in the panel of Mary's Visit to Elizabeth (see p. 34) made art history. It is the first identifiable landscape in Italian painting, a view of Lake Trasimeno as seen from Cortona.

Art in Tuscany | Fra Angelico | The annunciation

|

|

|

| |

|

|

In 1448, according to an early chronicle, Fra Angelico received from Piero de' Medici, Cosimo's son, the prestigious assignment to decorate the doors of a silver treasury for the new oratory to be constructed near the chapel of the Santissima, at Santissima Annunziata, among the most venerable churches in Florence. Fra Angelico did not begin work on this extensive series of small paintings until after his return from Rome in 14491 so. The silver treasury panels were the last major commission undertaken by Fra Angelico and he was evidently unable to bring the project to completion before he was called back to Rome, where he died in February 1455.

Although the themes and settings of the scenes are varied, Angelico united the ensemble with consistently scaled figures, architecture and horizons. The Annunciation takes place within a deep, open courtyard framed by twin porticos, inspired by the architecture of the church.

Throughout the cycle, parallel and prophetic texts amplify the resonance of every scene. In the Annunciation, the quotations from the Book of Isaiah and the Gospel of Luke are virtually identical in phrasing, confirming, according to Christian exegesis, that Isaiah's prophecy was fulfilled through the Incarnation and divinely ordered.

Art in Tuscany | Fra Angelico | Paintings for the Armadio degli Argenti (1451-52)

|

|

Annunciation, 1451-52, Museo di San Marco, Florence Annunciation, 1451-52, Museo di San Marco, Florence

|

| |

|

|

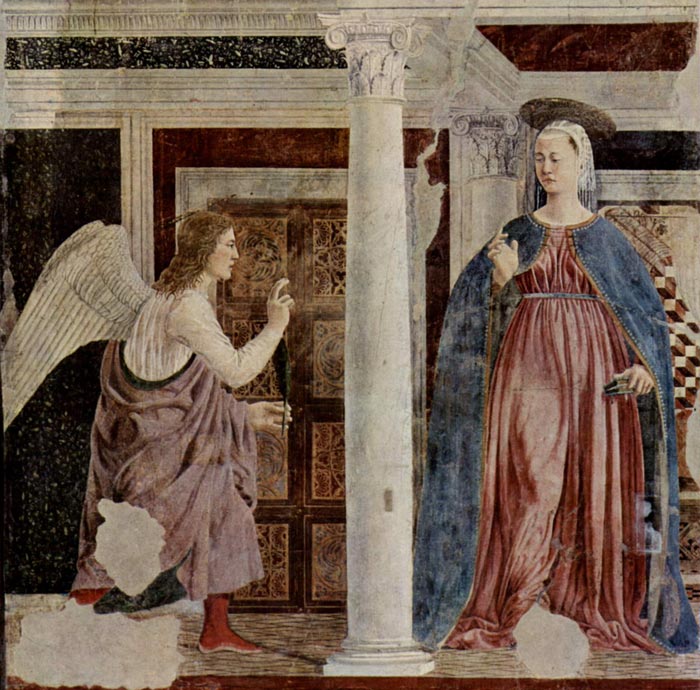

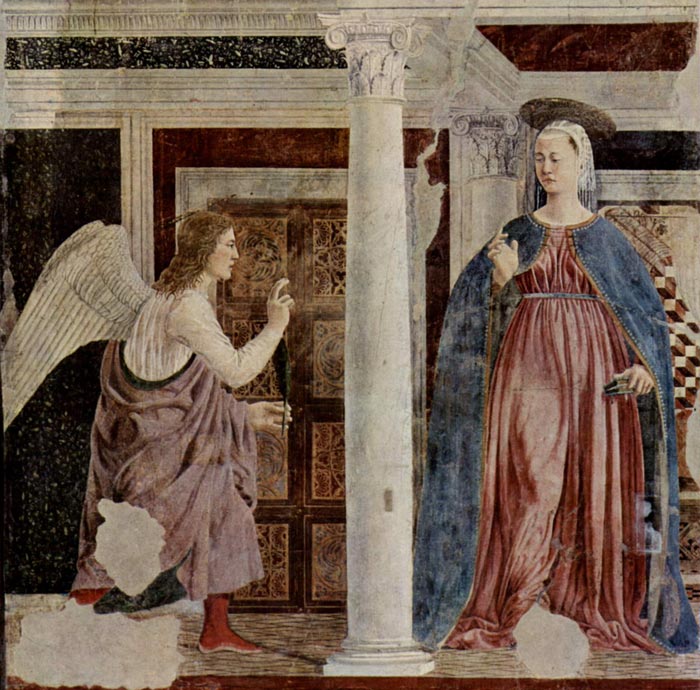

Piero della Francesca | The Annunciation to Mary

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, The Annunciation to Mary, c. 1455, fresco, 329 x 193 cm, San Francesco, Arezzo

|

The cycle ends with a depiction of the Annunciation, not strictly part of the Legend of the True Cross but probably included by Piero for its universal meaning.

With the scene of the Annunciation, the chronology of the story enters the time of the New Testament. This scene is not ordinarily included in the True Cross legend. Never inappropriate in cycles concerned with the theology of salvation, the Annunciation may have been required here in remembrance of the important indulgence, granted in 1298 and often renewed, awarded to all visitors who worshipped in the church on March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation.

Piero has created an ingenious four-part composition that combines heaven and earth. God-the-Father carried on clouds in the upper left quadrant emits golden rays from his hands. [Very little of the gold, applied after the plaster is dry, remains on any of the frescoes.] At the same moment the Angel Gabriel alights below, in the forecourt of Mary’s house. He is silhouetted against the intricately carved doorway, which is closed, fulfilling the prophecy of Ezekiel (44:2; perhaps represented in the figure depicted two tiers above). Gabriel proffers not a lily but a palm frond, thus announcing not only the incarnation of Christ but also the future death and compassion of Mary herself. The palm is known as the key to paradise, lost when Eve sinned but returned when Mary died. The sin of Eva is unlocked by this key as Gabriel utters the greeting Ave, its reverse.

Piero paints Mary as a massive figure, tall as a column (another of her epithets), of great nobility and acquiescence. Her scale and demeanor qualify her as a symbol of the Church, while her expression and grace are full of human warmth. Her house, the “Casa Santa,” is a marble-encrusted, classicizing dwelling. Through the open doorway, her thalamus or marriage-bed is visible, alluding to the Marriage of Christ and Ecclesia that is taking place at the Annunciation. In the upper right quadrant, the shadow of the tapestry bar passes through the hanging-loop, again symbolizing Mary’s unbroken virginity. More than any other scene, the Annunciation transforms medieval symbolism into a vista of the new rationally measured world of the Renaissance.

|

|

|

Sandro Botticelli

|

|

|

|

Sandro Botticelli (1444/45-1510), Annunciation (Annunciation of San Martino alla Scala), 1481, fresco. 243 x 550 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Photo © Gabinetto Fotografico, Polo Museale, Florence |

| |

Art in Tuscany | Sandro Botticelli , Annunciation (Annunciation of San Martino alla Scala)

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

Virgin Annunciate,by the Italian Renaissance artist Antonello da Messina, is housed in the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo, in southern Italy. Probably painted in Sicily in 1476, it shows Mary interrupted at her reading by the Angel of the Annunciation.

Antonello da Messina studied the Flemish artists, notably Jan van Eyck. Based on these experiences, when he returned to Venice he introduced oil painting and Flemish pictorial techniques into mid-15th-century Venetian art.

A masterpiece of Italian Renaissance art, Antonello's The Virgin Annunciate was created for a domestic interior. It is a haunting image of the adolescent Mary when the angel Gabriel announces to her that she will bear God's Son. The modest Sicilian female, attired in a simple blue mantle, is aloof and mysterious. She is shown bust-length and against a plain background. Mary looks up from behind a reading desk upon which her book of devotions rests. Her direct outward gaze and right hand raised in a blessing gesture engage the viewer, who replaces Gabriel as the provider of the miraculous news and becomes an active participant in the charming painting's story. The lack of a pendant or adjoining panel suggests that the angel's presence is implied.

Noteworthy in The Virgin Annunciate is Antonello's use of light to build convincing forms. To paint Mary's foreshortened right hand, he may have employed a velo, a stringed grid through which an artist observed objects and then recorded their contours onto a squared piece of paper. [2]

|

|

|

Case Vacanze Toscana | Artist and Writer's Residency | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

|

[1] The Christian celebration of the Annunciation on the 25th March marks the angel Gabriel's visit to Mary. In the Bible, the Annunciation is narrated in the book of Luke, Chapter 1, verses 26-38: Now in the sixth month, the archangel Gabriel was sent from God to a city of Galilee, named Nazareth, to a virgin pledged to be married to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David. The virgin's name was Mary. Having come in, the angel said to her, "Rejoice, you highly favored one! The Lord is with you. Blessed are you among women!" But when she saw him, she was greatly troubled at the saying, and considered what kind of salutation this might be. The angel said to her, "Don’t be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God. Behold, you will conceive in your womb, and bring forth a son, and will call his name ‘Jesus.’ He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his father, David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever. There will be no end to his Kingdom." Mary said to the angel, "How can this be, seeing I am a virgin?" The angel answered her, "The Holy Spirit will come on you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you. Therefore also the holy one who is born from you will be called the Son of God. Behold, Elizabeth, your relative, also has conceived a son in her old age; and this is the sixth month with her who was called barren. For everything spoken by God is possible." Mary said, "Behold, the handmaid of the Lord; be it to me according to your word." The angel departed from her.

Fra Filippo Lippi (1406 - October 8, 1469), also called Lippo Lippi, was an Italian painter of the Italian Quattrocento (15th century) school. Lippi was born in Florence to Tommaso, a butcher. Both his parents died when he was still a child. Mona Lapaccia, his aunt, took charge of the boy. In 1420 he was registered in the community of the Carmelite friars of the Carmine in Florence, where remained until 1432, taking the Carmelite vows in 1421 when he was sixteen. In his Lives of the Artists, Vasari says: "Instead of studying, he spent all his time scrawling pictures on his own books and those of others," The prior decided to give him the opportunity to learn painting. Eventually Fra Filippo quit the monastery, but it appears he was not released from his vows; in a letter dated 1439 he describes himself as the poorest friar of Florence, charged with the maintenance of six marriageable nieces.

[2] Barbera, Gioacchino, Keith Christiansen and Andrea Bayer. Antonello da Messina: Sicily's Renaissance Master (exh. cat.). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005, 12-30, 46-47.

[3] Foto d Di Sailko, licenziato in base ai termini della licenza Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported. |

|

|

|

Annunciation, 1451-52, Museo di San Marco, Florence

Annunciation, 1451-52, Museo di San Marco, Florence