|

||

| I T | Andrea del Castagno, Last Supper, 1447, fresco, Sant'Apollonia, Florence |

|

Andrea del Castagno, Last Supper, 1447 |

The first Renaissance refectory in Florence is the one belonging to the Benedictine nuns of Sant'Apollonia, created around 1445 in one of the most florid periods of the convent. Other three frescoes were discovered above this one, representing respectively the Resurrection, Crucifixion and Entombment of Christ. At the time of the restoration in 1952, the three frescoes were removed to be preserved, thus allowing the recovery of the splendid sinopites. |

|

Cenacolo of Sant’Apollonia with the Famous Men and Women by Andrea del Castagno, photograph from the beginning of the nineteenth century. Luchinat and Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani, ed. La tradizione fiorentina dei cenacoli. Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, 1997, p. 107. |

| The Cycle of Illustrious Men and Women is a work in fresco by Andrea del Castagno, painted for the Villa Carducci and Filippo Carducci between 1448 and 1451. Today the frescoes are divided between the Uffizi Gallery (frescoes of panels of distinguished men and women) and the Villa Carducci itself. The cycle was once covered with white plaster and was rediscovered in 1847 when the Grand Duke Leopold II bought the frescoes and had them removed. After being exhibited in the Museum Bargello in 1865, the detached frescoes were transferred to the museum Cenacolo di Sant'Apollonia. After the flood in Florence in 1966, they were again removed, to arrive at the Uffizi in 1969 where they were placed in the former church of San Pier Scheraggio. The hall of the deconsecrated church is now open only by appointment. |

| Andrea del Castagno (1423-1457) was well known for the emotional expressionism and naturalism of his figure style. It is often said that his Last Supper fresco exudes his greatest talent for balance between human figure and architecture. He stayed highly active in his later years, painting the his well known Famous Men and Women, in the Villa Carducci, displaying great minds such as Spano, Uberti, Dante and Boccaccio. In these larger-than-life–size series of portraits for a loggia of the Villa Carducci Pandalfini at Legnaia, Castagno broke with earlier styles and displayed more than mere craftsmanship. He portrayed movement of body and facial expression, creating dramatic tension. Castagno brought to painting what Banco and Donatello brought to sculpture for Florentine artists. This influence carried great weight through the Renaissance, finding a masterful pinnacle in the work of Michelangelo. |

|

||

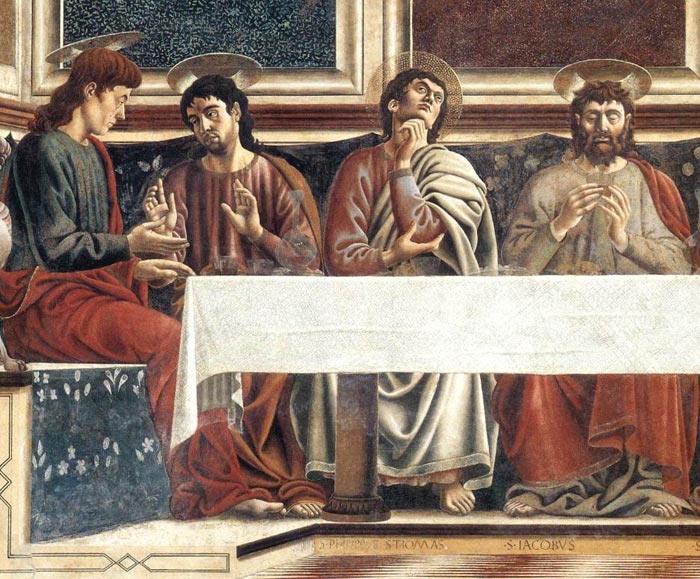

| All scholars agree in praising the sobre architectural structure of the room where the scene of the Last Supper is taking place: a room in the austere style of Alberti, with the lavish coloured marble panels functioning as a backdrop to the heavy and solemn scene of the banquet. Notice also the beauty of some of the minor details, such as the gold highlights in some of the characters' hair or the haloes depicted in perfect perspective. The detail and naturalism of this fresco portray the ways in which del Castagno departed from earlier artistic styles. The highly detailed marble walls hearken back to Roman "First Style" wall paintings, and that the pillars and statues recall Classical sculpture and preface trompe l'oeil painting. Furthermore, the color highlights in the hair of the figures, flowing robes, and a credible perspective in the halos foreshadow advancements to come. |

||

|

||

| The influence of Domenico Veneziano's painting is strong in the decoration of the refectory of Sant'Apollonia which Andrea painted between June and October 1447. He solved the problem posed by the height of the refectory walls in Sant'Apollonia by using the old method of arranging the scenes in two rows, one above the other, but he gave them a visual unity: the Stories of Christ's Passion frescoed on the upper level are in fact conceived as taking place in a space behind the room where the Last Supper on the lower level is happening.

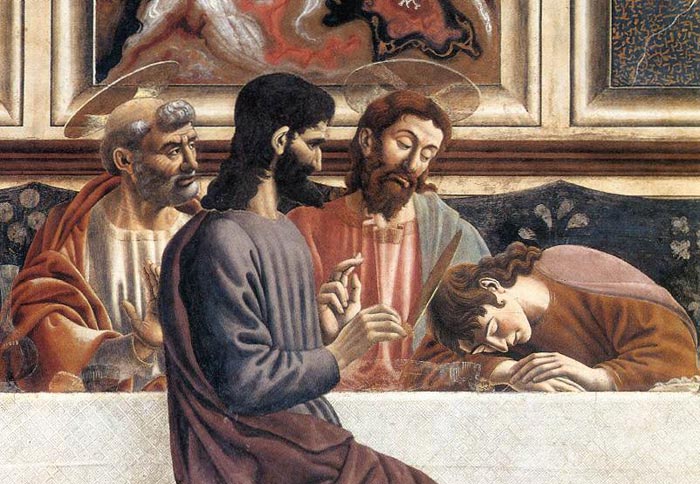

The Last Supper displays del Castagno's talents at his best. The arrangement of balanced figures in an architectural setting is particularly noted. For instance, Saint John's posture of innocent slumber neatly contrasts Jude the Betrayer's tense, upright pose, and the hand positions of the final pair of apostles on either end of the fresco mirror each other with accomplished realism. The colors of the apostles' robes and their postures contribute to the balance of the piece. The treatment of the Last Supper was a serious challenge for Renaissance painters, who had to depict thirteen figures while retaining diversity and interest. For this scene, Castagno created an engaging space with imitation marble wall plaques and the sharply foreshortened floor and ceiling. The figures are arranged behind a long narrow table, with the exception of the Apostle at each end and Judas Iscariot isolated on the front side. The central group, composed of four figures, Judas, Christ, Peter, and John, is visually emphasized by a dramatically coloured red marble slab. An extraordinary element of this fresco is the remarkable balance of gestures and expressions, particularly in the group of figures in the centre of the composition, where the innocent sleep of St John to the left of Jesus is contrasted to the tense, rigid figure of Judas sitting opposite. |

|

|

|

||

| The treatment of the Last Supper was a serious challenge for Renaissance painters, who had to depict thirteen figures while retaining diversity and interest. For this scene, Castagno created an engaging space with imitation marble wall plaques and the sharply foreshortened floor and ceiling. The figures are arranged behind a long narrow table, with the exception of the Apostle at each end and Judas Iscariot isolated on the front side. The central group, composed of four figures, Judas, Christ, Peter, and John, is visually emphasized by a dramatically coloured red marble slab. |

||

|

||

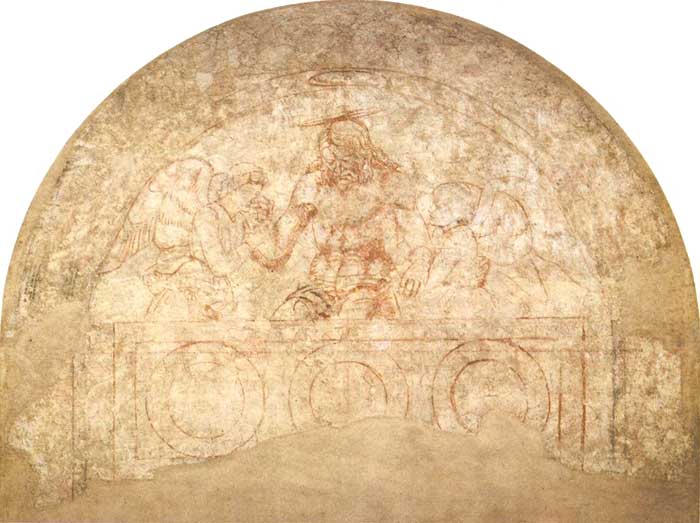

| The fresco of Christ in the Sepulchre with Two Angels was painted in the cloister of Sant'Apollonia. Here, as in the other frescoes, the composition is dominated by the perfect balance between the accurate geometrical construction and the genuine participation in the dramatic event.

The splendid synopia which was discovered when the fresco was detached from the wall is today on exhibit alongside the fresco itself. |

||

|

||

|

||

Andrea del Castagno, Christ in the Sepulchre with Two Angels (synopia), 1447, fresco in Sant'Apollonia, Florence |

||

[1] Andrea del Castagno (Italian, before 1419 - 1457) | The exact birth date of Andrea di Bartolo di Simone, called Andrea del Castagno, is not known; formerly estimated around 1390 on the basis of Vasari's indications, it has been established as shortly before 1419 by recent research. Andrea was born in a village in the Mugello area near Florence now called Castagno d'Andrea, and was probably trained in Florence. He was well enough known there in 1440 to receive the commission to paint, on the facade of the Bargello, the members of the Albizzi family and their friends hanging from their heels because they were declared rebels after the battle of Anghiari. For this work, destroyed in 1494, Andrea was given the nickname "Andreino degli Impiccati" (Andy of the Hanged Men). In 1442 he was in Venice, where with Francesco da Faenza he painted the signed and dated frescoes on the vault of the San Tarasio chapel in the church of San Zaccaria. The stylistically uniform decoration of the chapel, however, leads one to conclude that Francesco's intervention must have been marginal. The Venice murals, the earliest surviving dated work by Andrea, demonstrate his interest in using perspective foreshortening to impart monumentality and physical density to his athletic figures. The murals also show the influence of Paolo Uccello, Filippo Lippi, and above all, Donatello on the young artist. The following year Andrea was back in Florence, and at the beginning of 1444 he received payment for a cartoon of the Deposition for a window in the drum of the cathedral's dome. In these same years he also painted the Crucifixion with Camaldolese Saints for the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli (now in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova). On 30 May 1444 he joined the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, and over the next two years received various official commissions for works that have not survived. The presence in Florence of Domenico Veneziano--who, assisted by Piero della Francesca, worked in the church of Sant'Egidio (1439-1445)--was probably decisive for Andrea. Even without giving credence to Vasari's story about Andrea's envy of Domenico, he was certainly influenced by the latter's clear, luminous palette and rigorous perspective constructions, with solutions often very near to or foreshadowing those of Piero della Francesca. The c. 1444 fresco decoration of the Pazzi chapel in the Villa del Trebbio (some fragments of which are still in situ, whereas the Madonna and Child with Two Saints is now detached and forms part of the Contini-Bonacossi bequest to the Uffizi) brings him another step closer to Domenico Veneziano. An intense, almost Flemish interest in reflected light informed his luminous vision and realistic rendering of detail, reaching its highest point on the west wall of the refectory of the former monastery (now museum) of Sant'Apollonia, where in 1447 Andrea frescoed the Last Supper and episodes from the Passion and Resurrection of Christ. From this period also are the lunette of the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, originally painted above a door of the same monastery, and a Crucifixion with Saints Benedict and Romuald, formerly in the cloister of Santa Maria degli Angeli (both are now detached and in the museum of Sant'Apollonia). The Assumption of the Virgin between Saints Julian and Minias (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), painted between 1449 and 1450 for the church of San Miniato fra le Torri in Florence, was followed immediately by the fresco decoration of the large hall of Villa Carducci at Legnaia, with its Famous Men series, datable to 1449-1451. Some fragments of the cycle are still in situ, while the principal figures have been detached and are exhibited in the Uffizi. Between 1451 and 1453 Andrea frescoed three stories from the life of the Virgin in the church of Sant'Egidio, continuing the work begun by Domenico Veneziano; the cycle, completed by Baldovinetti, has since been destroyed. Similarly lost is the fresco of Lazarus, Martha, and Mary Magdalene, commissioned from Andrea in 1455 for the tomb of Orlando de' Medici in the church of Santissima Annunziata, presumably executed shortly after the surviving frescoes in the second and third chapels of the church, with Saint Julian and a Blessing Christ in one, and in the other Saint Jerome between Saints Paula and Eustochium beneath an image of the Holy Trinity. In 1456 Andrea painted the fresco in Santa Maria del Fiore of the equestrian monument to Niccolò da Tolentino, and in 1457 the Last Supper (lost in 2002) in the refectory of Santa Maria Nuova. Andrea's very intense activity was interrupted by his sudden death, probably from the plague, in 1457. [This is the artist's biography published, or to be published, in the NGA Systematic Catalogue | www.nga.gov ] |

||

|

Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance painting This article incorporates text from the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913, a publication now in the public domain, and uses material from the Wikipedia article Andrea del Castagno, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||

Holiday homes in the Tuscan Maremma | Podere Santa Pia |

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

||

|

||||

Villa I Tatti |

Siena, Duomo |

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence |

||

The façade and the bell tower of San Marco in Florence |

Florence, Orsan Michele |

Florence, San Miniato al Monte |

||

Florence | Transport |

||||

| Choosing one of the Florence walking tours you'll be able to visit the world-famous museums of the Uffizi and Accademia Galleries, discovering the main historical and artistic treasures of the city. The tours focus on Florence's major sights and attractions, including the Duomo, the Ponte Vecchio and the city's famous churches and Renaissance palaces. Novelist Henry James called Florence a “rounded pearl of cities -- cheerful, compact, complete -- full of a delicious mixture of beauty and convenience.” The best way to experience the Italian city’s artistry, history and joy of life is by walking the same paths that the Medicis, Michelangelo and James once used. And to reach Villa I Tatti, there is the itinerary From Fiesole to Settignano. 1 | A Walk Around the Uffizi Gallery 2 | Quarter Duomo and Signoria Square 3 | Around Piazza della Repubblica 5 | San Niccolo Neighbourhood in Oltrarno |

San Miniato al Monte |

|||