|

|

Sandro Botticelli, Primavera, c. 1486, Uffizi Gallery, Florence |

|

Sandro Botticelli | Primavera |

| Primavera, also known as Allegory of Spring, is a tempera panel painting by Italian Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli. Most critics agree that the painting, depicting a group of mythological figures in a garden, is allegorical for the lush growth of Spring. Other meanings have also been explored. Among them, the work is sometimes cited as illustrating the ideal of Neoplatonic love. The painting itself carries no title and was first called La Primavera by the art historian Giorgio Vasari who saw it at Villa Castello, just outside Florence, in 1550.[2] Vasari’s contemporaries were not particularly baffled by its secret. He simply writes: “Venus with the Graces who cover her with flowers, representing Spring.”The Medici family of Florence has become synonymous with the extraordinary cultural phenomenon called the Italian Renaissance.[3] The history of the painting is not certainly known, though it seems to have been commissioned by one of the Medici family. It contains references to the Roman poets Ovid and Lucretius, and may also reference a poem by Poliziano. Since 1919 the painting has been part of the collection of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy. Composition |

||

The painting features six female figures and two male, along with a blindfolded putto, in an orange grove. To the right of the painting, a flower-crowned female figure stands in a floral-patterned dress scattering flowers, collected in the folds of her gown. |

Mercury may have been modeled after Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici,[18] or possibly his cousin Giuliano de' Medici.[19] |

|

Various interpretations of the figures have been set forth, but it is generally agreed that at least at one level the painting is, as characterized by Cunningham and Reich (2009), "an elaborate mythological allegory of the burgeoning fertility of the world."[1] Elena Capretti in Botticelli (2002) suggests that the typical interpretation is thus:

This is a tale from the fifth book of Ovid's Fasti in which the wood nymph Chloris's naked charms attracted the first wind of Spring, Zephyr. Zephyr pursued her and as she was ravished, flowers sprang from her mouth and she became transformed into Flora, goddess of flowers. In Ovid's work the reader is told 'till then the earth had been but of one colour'. From Chloris' name the colour may be guessed to have been green - the Greek word for green is khloros, the root of words like chlorophyll - and may be why Botticeli painted Zephyr in shades of bluish-green.[8]

|

||

| The origin of the painting is somewhat unclear. It may have been created in response to a request in 1477 of Lorenzo de' Medici,[20] or it may have been commissioned somewhat later by Lorenzo or his cousin Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici.[21][22] One theory suggests Lorenzo commissioned the portrait to celebrate the birth of his nephew Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici (who would one day become Pope), but changed his mind after the assassination of Giulo's father, his brother Giuliano, having it instead completed as a wedding gift for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, who married in 1482.[7] It is frequently suggested that Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco is the model for Mercury in the portrait, and his bride Semirande represented as Flora (or Venus).[18][23][24][25] It has also been proposed that the model for Venus was Simonetta Vespucci, wife of Marco Vespucci and perhaps the mistress of Giuliano de' Medici (who is also sometimes said to have been the model for Mercury).[19] The painting overall was inspired by a description the Roman poet Ovid wrote of the arrival of Spring (Fasti, Book 5, May 2), though the specifics may have been derived from a poem by Poliziano.[26][27] As Poliziano's poem, "Rusticus", was published in 1483 and the painting is generally held to have been completed around 1482,[2][28] some scholars have argued that the influence was reversed.[29] Another inspiration for the painting seems to have been the Lucretius poem "De rerum natura", which includes the lines, "Spring-time and Venus come, and Venus' boy, / The winged harbinger, steps on before, / And hard on Zephyr's foot-prints Mother Flora, / Sprinkling the ways before them, filleth all / With colors and with odors excellent."[30][31] Whatever the truth of its origin and inspiration, the painting was inventoried in the collection of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici in 1499.[32] Since 1919, it has hung in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. During the Italian campaign of World War Two, the picture was moved to Montegufoni Castle about ten miles south west of Florence to protect it from wartime bombing.[33] It was returned to the Uffizi Gallery where it remains to the present day.[34] In 1982, the painting was restored.[35] The work has darkened considerably over the course of time.[27] |

||

| Youtube BBC The Private Life of a Masterpiece - La Primavera, Sandro Botticelli |

[1] Cunningham & Reich 2009, p. 282. |

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Sandro Botticelli and Primavera (painting), published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

Numerous other towns and villages offer a treasure trove of history and art waiting to be discovered. The central location of the holiday home allows you to visit the nearby beautiful villages Montalcino, Sant'Antimo, Pienza, S. Quirico d'Orcia and in the south Saturnia and Sorano - known for its beautiful Sasso Leopoldo. And the sea is 38km away in Marina di Grosseto. Off the beaten trackand nestled in a natural amphitheatre of rolling hills, Podere Santa Pia is the ideal choice for those seeking a peaceful, uncontaminated environment, yet still within easy reach of the the famous Tuscan cities, food and wines. Slow food and slow travel are part of a movement to return to traditional ways of traveling. Wine tasting in Tuscany is practically an obligation in this region of rolling vineyards and hidden, historic wine-properties. Hidden secrets and holiday houses in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia| Artist and writer's residency in spring and autumn

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, April |

Spring in Tuscany: century-old olive trees, between Podere Santa Pia and Cinigiano |

||

Vasari Corridor, Florence

|

Florence |

Florence, Duomo |

||

|

|

|||

Sovicille |

Siena, Palazzo Publicco |

Sunsets in Tuscany |

||

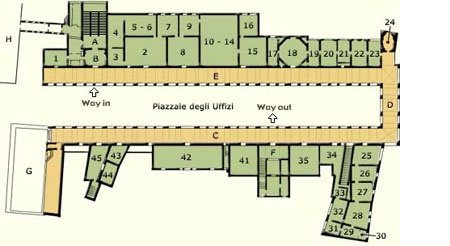

Galleria degli Uffizi

|

||||

Galleria degli Uffizi

All of Florence’s state-run museums belong to an association called Firenze Musei,

|

S E C O N D F L O O R

|

|||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, morning view on the Maremma from the northern terrace. Even after a wet spring,

the hills hereabouts tended to amber, umber and shades in between.

Tuscan Spring |

||||