|

|

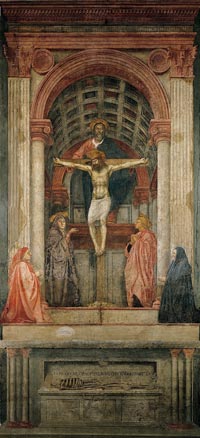

Masaccio, Trinity, (detail) 1425-28, fresco, 640 x 317 cm, Santa Maria Novella, Florence |

|

Masaccio | The Holy Trinity, Santa Maria Novella, Firenze |

The Holy Trinity, with the Virgin and Saint John and donors (Italian: Santa Trinità ) is a fresco by the Early Italian Renaissance painter Masaccio. It is located in the Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella, in Florence. Trinity is the most famous work of Masaccio beside the frescoes in the Cappelle Brancacci. There are various opinions as to exactly when this fresco was painted between 1425 and 1428. It was described in detail by Vasari in 1568, who emphasized the virtuosity of the trompe l'oeil in the architectural structure of the painting: "a barrel vault drawn in perspective, and divided into squares with rosettes which diminish and are foreshortened so well that there seems to be a hole in the wall." |

||

The most likely interpretation of the Trinity is that the painting alludes to the traditional medieval double chapel of Golgotha, with Adam's tomb in the lower part (the skeleton) and the Crucifixion in the upper part. But it can also assume the significance of the journey the human spirit must undertake to reach salvation, rising from the earthly life (the corruptible body) through prayer (the two petitioners) and the intercession of the Virgin and saints (John the Evangelist) to the Trinity.

WIKI The Trinity is noteworthy for its inspiration taken from ancient Roman triumphal arches and the strict adherence to the recent perspective discoveries, with a vanishing point at the viewer's eye level, so that, as Vasari describes it 'a barrel vault drawn in perspective, and divided into squares with rosettes that diminish and are foreshortened so well that there seems to be a hole in the wall.' This artistic technique is called trompe l'oeil, which means 'deceives the eye,' in French. Several diverse interpretations of the fresco have been proposed. Most scholars have seen it as a traditional kind of image, intended for personal devotions and commemorations of the dead, although explanations of how the painting reflects these functions differ in their details. |

|

|

Alberti's Perspective Construction and One-point perspective | The location of the eye in Masaccio's Trinity | Tony Phillips, Alberti’s perspective construction, the January, 2002, AMS Feature Column One-point perspective is the most common systematic method for representing space on a surface. The idea is that the picture in its frame should give the illusion of being a window through which the immobile eye of the observer looks at an outside 3-dimensional world. (Alberti speaks of the canvas as ``an open window through which I see what I want to paint.'') Each spot visible through the window gives a spot in the picture, located at the intersection with the picture plane of the straight line joining it to the eye. The Magic of Illusion — presented here in a seven-part podcast series — is a film about how we see, what we see, or what it is we think we see. Al Roker guides us on a journey into the secrets of illusion, utilizing special effects to illustrate the artistic and visionary discoveries of the Renaissance. While Copernicus and Columbus were changing our understanding of the world, the Renaissance masters were dramatically changing the way we see that world. The film uses recent technology to look at old works in new ways. Each segment of this podcast presentation unlocks new secrets of illusion and perspective as seen in the works of old masters. This program made possible by The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations. In 1427 inside Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Masaccio created the masterpiece The Trinity using linear perspective for the first time. This segment explains how he was able to make the wall behind the work seem to disappear so that the painting becomes an extension of the room the viewer is in. Part 2 | Masaccio's Trinity in Santa Maria Novella, Firenze |

|

|

||||

Santa Trinita in Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

San Marco, Florence |

||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

||||

|

||||

Castello Banfi |

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

||

Santa Maria Novella a Firenze |

The Valle d'Ombrone |

Santa Maria del Carmine, Firenze |

||

|

||||

Podere Santa Poa offers its guests a breathtaking view over the Maremma hills and Montecristo, the island in the Tyrrhenian Sea |

||||