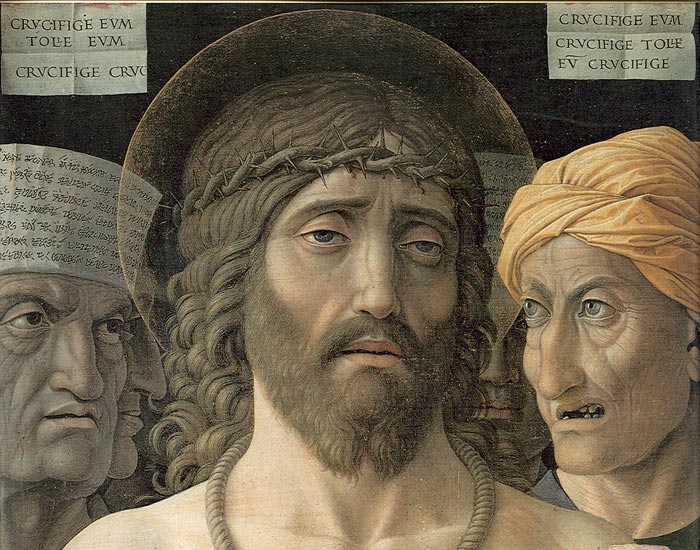

[1] The Mantegna of the end is in very point comparable to the final period of the great Italian painters of modern times, rather solitary and meditating with profound introspection on episodes of the Passion – one thinks of Titian or Caravaggio, among others.The ecce Homo of the Musée Jacquemart-André (cat. 183) which was underestimated for a long time falls within this movement, as does the Christ Carrying the Cross with Simon of Cyrene from Verona (cat 188). Although the autograph nature of the latter is sometimes questioned, its very close framing must be associated with the inventions on the same theme of the great European artists around 1500: Leonardo, Giorgione or Bosch[[It is obviously essential to add to this “tragic series” the final St. Sebastian, found in Mantegna’s studio after his death and today in the Ca’d’Oro in Venice.

[2] Ecce Homo are the Latin words used by Pontius Pilate in the Vulgate translation of the John 19:5, when he presents a scourged Jesus Christ, bound and crowned with thorns, to a hostile crowd shortly before his Crucifixion. James Version translates the phrase into English as Behold the Man. The scene is widely depicted in Christian art.

The Ecce homo is a standard component of cycles illustrating the Passion and Life of Christ in art. It follows the Flagellation of Christ, the Crowning with thorns and the Mocking of Christ, the last two often being combined. The usual depiction shows Pilate and Christ, the mocking crowd and parts of the city of Jerusalem, but from the 15th century devotional pictures are found of Jesus alone, in half or full figure with a purple robe, loincloth, crown of thorns and torture wounds, especially on his head. Similar subjects but with the wounds of the crucifixion showing (Nail wounds on the limbs, spear wounds on the sides), are termed a Man of Sorrow(s) (also Misericordia), and if the "Instruments of the Passion" are present it may be called an Arma Christi. If Christ is sitting down (usually supporting himself with his hand on his thigh), it may be referred to it as Christ at rest or Pensive Christ. It is not always possible to distinguish these subjects.

The first depictions of the ecce homo scene in the arts appear in the 9th and 10th centuries in Syrian-byzantine culture. Western depictions in the Middle Ages that often seem to depict the ecce homo scene, (and are usually interpreted as such) more often than not only show the crowning of thorns and the mocking of Christ, (cf. the Egbert Codex and the Codex Aureus Epternacensis) which precede the actual ecce homo scene in the Bible. The independent image only developed around 1400, probably in Burgundy, but then rapidly became extremely popular, especially in Northern Europe.

The motif found increasing currency as the Passion became a central theme in Western piety in the 15th and 16th centuries. The ecce homo theme was included not only in the passion plays of medieval theatre, but also in cycles of illustrations of the story of the Passion, as in the Passions of Albrecht Dürer or the prints of Martin Schongauer. The scene was (especially in France) often depicted as a sculpture or group of sculptures; even altarpieces and other paintings with the motif were produced (by, for example, Hieronymus Bosch or Hans Holbein). Like the passion plays, the visual depictions of the ecce homo scene, it has been argued, often, and increasingly, portray the people of Jerusalem in a highly critical light, bordering perhaps on antisemitic caricatures. Equally, this style of art has been read as a kind of simplistic externalisation of the inner hatred of the angry crowd towards Jesus, not necessarily implying any racial judgment.

The motif of the lone figure of a suffering Christ who seems to be staring directly at the observer, enabling him/her to personally identify with the events of the Passion, arose in the late Middle Ages. A parallel development was that the similar motifs of the Man of Sorrow and Christ at rest increased in importance. The subject was used repeatedly in later prints (for example, by Jacques Callot and Rembrandt), the paintings of the Renaissance and the Baroque, as well as in Baroque sculptures.

Hieronymus Bosch painted his first ecce homo during the 1470s.[2] He returned to the subject in 1490 to paint in a characteristically Netherlandish style, with deep perspective and a surreal ghostly image of praying monks in the lower left-hand corner.

In 1498, Albrecht Dürer depicted the suffering of Christ in the ecce homo scene of his Great Passion in unusually close relation with his self-portrait, leading to a reinterpretation of the motif as a metaphor for the suffering of the artist. As a representation of the injustice of critique, James Ensor used the ecce homo motif in his ironic print Christ and the Critics(1891), in which he portrayed himself as Christ.

Especially in the 19th and 20th centuries, the meaning of ecce homo motif has been extended to the portrayal of suffering and the degradation of humans through violence and war. Famous modern depictions are: Lovis Corinth's later work Ecce Homo (1925), which shows, from the perspective of the crowd, Jesus, a soldier and Pilate dressed as a physician, and Otto Dix's Ecce homo with self-likeness behind barbed wire (1948). Joe Forkan has painted a 2009 version.

|

Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects

Art in Tuscany | Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

Volume III | Filarete And Simone To Mantegna

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects, Giorgio Vasari | download pdf

Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects | Andrea Mantegna

The André’ Jacquemart's "Italian Museum" is a stunning showcase for an extensive collection of Italian Quattrocento artworks and the pride of the Musée Jacquemart-André. The choice of works faithfully reflects the personal taste of Edouard André and Nélie Jacquemart.

Here, Edouard André showed his preference for Venetian painters like or Bellini or Mantegna, several of whose works he acquired, such as the moving Ecce Homo. Nélie Jacquemart, for her part, preferred the Florentine artists such as Ucello, Botticini, Bellini or Perugino.

Andre Jacquemart Museum, Paris | www.musee-jacquemart-andre.com

|