[1] Giotto di Bondone was a Florentine painter and architect. Outstanding as a painter, sculptor, and architect, Giotto was recognized as the first genius of art in the Italian Renaissance. Giotto lived and worked at a time when people's minds and talents were first being freed from the shackles of medieval restraint. He dealt largely in the traditional religious subjects, but he gave these subjects an earthly, full-blooded life and force.

The artist's full name was Giotto di Bondone. He was born about 1266 in the village of Vespignano, near Florence. His father was a small landed farmer. Giorgio Vasari, one of Giotto's first biographers, tells how Cimabue, a well-known Florentine painter, discovered Giotto's talents. Cimabue supposedly saw the 12-year-old boy sketching one of his father's sheep on a flat rock and was so impressed with his talent that he persuaded the father to let Giotto become his pupil. Another story is that Giotto, while apprenticed to a wool merchant in Florence, frequented Cimabue's studio so much that he was finally allowed to study painting.

The earliest work attributed to Giotto is a series of frescoes on the life of St Francis in the church at Assisi. In about 1305 and 1306 Giotto painted the extraordinary series of frescoes in the Arena Chapel in Padua.

Vasari tells the story of how Pope Boniface VIII sent a messenger to Giotto with a request for samples of his work. Giotto dipped his brush in red and with one continuous stroke painted a perfect circle. He then assured the messenger that the worth of this sample would be recognized. When the pope saw it, he "instantly perceived that Giotto surpassed all other painters of his time."

In Rome, Naples, and Florence, Giotto executed commissions from princes and high churchmen. The Peruzzi and Bardi chapels in the Church of Santa Croce are adorned by Giotto's frescoes.

In 1334 the city of Florence honored Giotto with the title of Magnus Magister (Great Master) and appointed him city architect and superintendent of public works. In this GIOTTO di Bondone (b. 1267, Vespignano, d. 1337, Firenze) capacity he designed the famous Campanile (bell tower). He died in 1337, before the work was finished.

Giotto was short and homely, and he was a great wit and practical joker. He was married and left six children at his death. Unlike many of his fellow artists, he saved his money and was accounted a rich man. He was on familiar terms with the pope, and King Robert of Naples called him a good friend.

In common with other artists of his day, Giotto lacked the technical knowledge of anatomy and perspective that later painters learned. Yet what he possessed was infinitely greater than the technical skill of the artists who followed him. He had a grasp of human emotion and of what was significant in human life. In concentrating on these essentials he created compelling pictures of people under stress, of people caught up in crises and soul-searching decisions. Modern artists often seek inspiration from Giotto. In him they find a direct approach to human experience that remains valid for every age.

Giotto is regarded as the founder of the central tradition of Western painting because his work broke free from the stylizations of Byzantine art, introducing new ideals of naturalism and creating a convincing sense of pictorial space. His momentous achievement was recognized by his contemporaries (Dante praised him in a famous passage of The Divine Comedy, where he said he had surpassed his master Cimabue), and in about 1400 Cennino Cennini wrote 'Giotto translated the art of painting from

Greek to Latin.'

In spite of his fame and the demand for his services, no surviving painting is documented as being by him. His work, indeed, poses some formidable problems of attribution, but it is universally agreed that the fresco cycle in the Arena Chapel at Padua is by Giotto, and it forms the starting-point for any consideration of his work. The Arena Chapel (so-called because it occupies the site of a Roman arena) was built by Enrico Scrovegni in expiation for the sins of his father, a notorious usurer mentioned by Dante. It was begun in 1303 and Giotto's frescos are usually dated c. 1305-06. They run right round the interior of the building; the west wall is covered with a Last Judgment, there is an Annunciation over the chancel arch, and the main wall areas have three tiers of paintings representing scenes from the life of the Virgin and her parents, St Anne and St Joachim, and events from the Passion of Christ. Below these scenes are figures personifying Virtues and Vices, painted to simulate stone reliefs - the first grisailles. The figures in the main narrative scenes are about half-size, but in reproduction they usually look bigger because Giotto's conception is so grand and powerful. His figures have a completely new sense of three-dimensionality and physical presence, and in portraying the sacred events he creates a feeling of moral weight rather than divine splendor. He seems to base the representations upon personal experience, and no artist has surpassed his ability to go straight to the heart of a story and express its essence with gestures and expressions of unerring conviction.

The other major fresco cycle associated with Giotto's name is that on the Life of St Francis in the Upper Church of S. Francesco at Assisi. Whether Giotto painted this is not only the central problem facing scholars of his work, but also one of the most controversial issues in the history of art. The St Francis frescos are clearly the work of an artist of great stature (their intimate and humane portrayals have done much to determine posterity's mental image of the saint), but the stylistic differences between these works and the Arena Chapel frescos seem to many critics so pronounced that they cannot accept a common authorship. Attempts to attribute other frescos at Assisi to Giotto have met with no less controversy.

There is a fair measure of agreement about the frescos associated with Giotto in Santa Croce in Florence. He probably painted in four chapels there, and work survives in the Peruzzi and Bardi chapels, probably dating from the 1320s. The frescos are in very uneven condition (they were whitewashed in the 18th century), but some of those in the Bardi Chapel on the life of St Francis remain deeply impressive.

Nothing survives of Giotto's work done for Robert of Anjou in Naples, and the huge mosaic of the Ship of the Church (the Navicella) that he designed for Old St Peter's in Rome has been so thoroughly altered that it tells us nothing about his style. In Rome he would have seen the work of Pietro Cavallini, which was as important an influence on him as that of his master Cimabue.

Several panel paintings bear Giotto's signature, notably the Stefaneschi Altarpiece (Vatican), done for Cardinal Stefaneschi, who also commissioned the Navicella, but it is generally agreed that the signature is a trademark showing that the works came from Giotto's shop rather than an indication of his personal workmanship. On the other hand, the Ognissanti Madonna (Uffizi, Florence, c. 1305-10) is neither signed nor firmly documented, but is a work of such grandeur and humanity that it is universally accepted as Giotto's.

Among the other panels attributed to him, the finest is the Crucifix in Sta Maria Novella, Florence. On account of his great fame as a painter, Giotto was appointed architect to Florence Cathedral in 1334; he began the celebrated campanile, but his design was altered after his death.

In the generation after his death he had an overwhelming influence on Florentine painting; it declined with the growth of International Gothic, but his work was later an inspiration to Masaccio, and even to Michelangelo. These two giants were his true spiritual heirs.

[2] In 1300, the wealthy Paduan merchant Enrico Scrovegni bought a piece of land on the site of a former Roman arena. Included in the palace that he built on the site was a chapel dedicated to the Virgin of the Annunciation, Santa Maria Annunziata, and the Virgin of Charity, Santa Maria del Carità. Enrico is shown in the fresco of the Last Judgement presenting a model of the chapel to the Virgin.

The family wealth had been amassed by Enrico's father, Reginaldo, whom Dante singled out as the arch usurer in his Inferno. Usury, the lending of money for profit, was considered a sin during the Middle Ages. It is likely that Enrico constructed the chapel as a means to expiate the father's sin. The dedication of the Chapel to the Virgin of Charity, referred to in a document of March of 1304 in which Pope Benedict XI granted indulgences to those who visited "Santa Maria del Carità de Arena," was an obvious choice to disassociate the family from taint of greed and miserliness.

The theme of usury is developed in a number of frescoes in the Arena Chapel. This is most evident in the prominent positioning of the scene of Judas being paid for betraying Christ on the north side of the Chancel Arch adjacent to the altar.

But the theme of usury is also developed in the adjacent image of Christ expelling the merchants from the Temple and the detail of usurers hanging from the their money bags in the Hell scene included in the Last Judgment.

The size and splendor of the Arena Chapel offended the monks of the neighboring Eremitani Church, who lodged a complaint before the Episcopal Curia in Padua. We, thus, can see the Arena Chapel as both a token of Enrico Scrovegni's piety and his contrition for the sins of his father and also as a symbol of his family's status as wealthy merchants who are emulating the aristocracy with the lavish palace and private family chapel. Enrico Scrovegni's seeming conflicting motivations in commissioning the Arena Chapel is brought out in the following passage:

"Among the factors that relate specifically to Enrico Scrovegni are a possible desire to expiate his father's usury and at the same time to make his own expenditure conspicuous; an ambition for status combined with a fear of damnation; a desire, on the one hand, to be regarded as an ascetic devoted to the cult of the Virgin, and, on the other, to secure for himself a fitting property to serve as his personal monument (Source:Diana Norman, Siena, Florence, and Padua: Art, Society and Religion 1280-1400, Volumr II: Case Studies, p. 92)."

It is likely that the Chapel was formally consecrated on March 25, 1305, the Feast of the Annunciation. An entry in the records for March 16,1305 of the High Council of Venice documents the lending of tapestries to Enrico Scrovegni on the occasion of the dedication of his chapel.

The earliest reference to Giotto's frescoes in the Arena Chapel is found in an allegorical poem entitled The Documents of Love written by Francesco da Barberino between 1308-1313. The text refers to a figure of Envy that "Giotto painted excellently in the Arena at Padua.

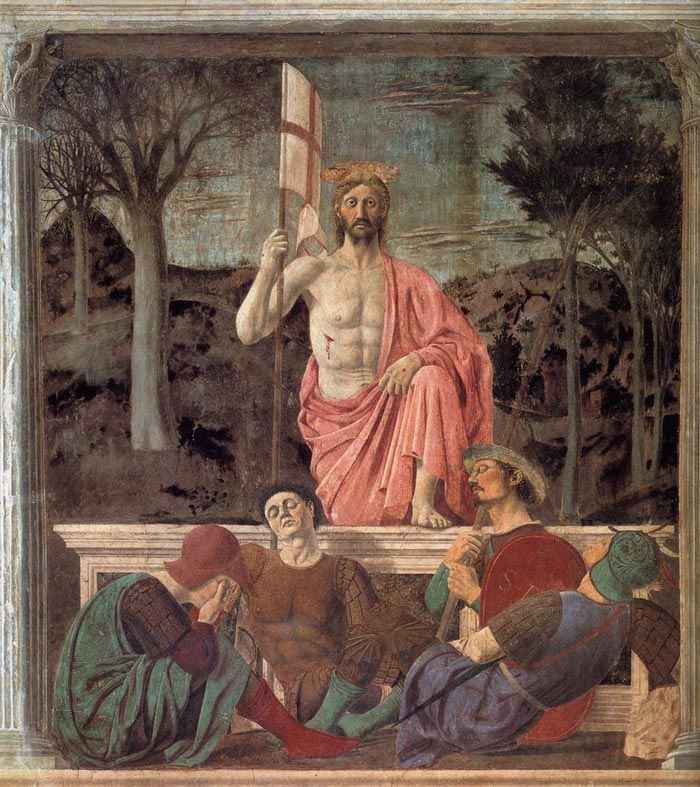

[3] Marco Bussagli, Piero Della Francesca, p. 24, Giunti Editore, 2007

Sito ufficiale | www.cappelladegliscrovegni.it

Tour virtuale della Cappella degli Scrovegni | Riproduzione digitale in alta definizione degli affreschi di Giotto agli Scrovegni

Giotto. Cappella Scrovegni. Il Restauro | The restauration | pdf | www.giottoagliscrovegni.it

|