| |

|

| The Basilica di Santa Croce is the principal Franciscan church in Florence. It is situated on the Piazza di Santa Croce. The site, when first chosen, was in marshland outside the city walls. Legend says that Santa Croce was founded by St Francis himself. It is the burial place of some of the most illustrious Italians, such as Michelangelo, Galileo, Machiavelli, Foscolo, Gentile and Rossini.

Its most notable features are its sixteen chapels, many of them decorated with frescoes by Giotto and his pupils, and its tombs and cenotaphs.[1]

According to Lorenzo Ghiberti, Giotto painted chapels for four different Florentine families in the church of Santa Croce, although he does not identify which chapels they were. It is only with Vasari that the four chapels are identified: the Bardi Chapel (Life of St. Francis), the Peruzzi Chapel (Life of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, perhaps including a polyptych of Madonna with Saints now in the Museum of Art of Raleigh, North Carolina) and the lost Giugni Chapel (Stories of the Apostles) and the Tosinghi Spinelli Chapel (Stories of the Holy Virgin). As with almost everything in Giotto's career, the dates of the fresco decorations that survive in Santa Croce are disputed. The Bardi Chapel, immediately to the right of the main chapel of the church, was painted in true fresco, and to some scholars the simplicity of its settings seems relatively close to those of Padua, while the Peruzzi Chapel's more complex settings suggest a later date. The Peruzzi Chapel is adjacent to the Bardi Chapel and was largely painted a secco. This technique, quicker but less durable than true fresco, has resulted in a fresco decoration that survives in a seriously deteriorated condition. Scholars who date this cycle earlier in Giotto's career see the growing interest in architectural expansion that it displays as close to the developments of the giottesque frescoes in the Lower Church at Assisi, while the Bardi frescoes have a new softness of color that indicates the artist going in a different direction, probably under the influence of Sienese art, and so must be a later development.

Restorers using ultra-violet rays have rediscovered rich original details of Giotto's paintings in the Peruzzi Chapel in Florence's Santa Croce church that have been hidden for centuries.[3]

Giotto also received the commission for the second surviving chapel in the Franciscan church of Santa Croce in Florence from a banker. The donor Ridolfo de' Bardi and his brother jointly inherited their father's banking house and commercial interests. This involved maintaining a good relationship with the powers who determined the politics of the day - with the pope, with the Neapolitan ruling house of Anjou, and with the Guelph party. He was able to go on cultivating this highly effective mixture of faith, politics and money for the next three decades until his house went bankrupt in the 1340s.

The Bardi family chapel is situated to the right of the choir, which means that it is the first chapel of the southern transept, and dedicated to St. Francis. As was the case with the neighboring Peruzzi Chapel, these frescoes were also painted over in the 18th century, rediscovered in the 19th century, and reworked. During their restoration in the middle of our own century, all reworked areas were removed and the ruined parts sealed with plaster. For this reason, some of the frescoes have empty spaces, although the actual painting is considerably better preserved here than in the Peruzzi Chapel, since Giotto went back to working with fresh plaster here.

As in the Peruzzi chapel, three frescoes framed by ornamental bands decorate each wall. But unlike in the former, these are dedicated to just the one saint, St. Francis. The Renunciation of Worldly Goods and the Confirmation of the Rule are situated in the lunettes. In the middle register the Apparition at Arles and the Trial by Fire before the Sultan are depicted. The Death of St. Francis and Inspection of the Stigmata and the Apparition at Aries can be seen at eye level. Above the entrance to the chapel the Stigmatisation is portrayed, as it were, as a summation of the life of the saint. The seraphim from whom Francis receives the stigmata here appears — unlike at Assisi or in the panel in the Musée du Louvre — as the crucified Christ.

While the St Francis in the paintings in the Upper Church at Assisi wears a beard, Giotto depicts him without one here, as in the vault frescoes in the Lower Church. This manifestation of the saint, favoured by the order since 1316, must have been particularly agreeable to a banker, since it no longer expressed the original significance of personal poverty.

Unlike the Peruzzi Chapel, the construction of the architecture portrayed in the frescoes is here based on a viewpoint within the chapel. The perspective of the architectural structures in the paintings changes with great logical consistency — the higher the register, the greater the foreshortening from below. This only increases the impression of fluidity between real and painted space.

Art in Tuscany | Giotto di Bondone | The Bardi Chapel in Santa Croce, Florence

|

The Peruzzi Chapel pairs 3 frescoes from the life of St. John the Baptist (The Annunciation of John's Birth to his father Zacharias; The Birth and Naming of John; The Feast of Herod) on the left wall with 3 scenes from the life of St. John the Evangelist (The Visions of John on Ephesus; The Raising of Drusiana; The Ascension of John) on the right wall. The choice of scenes has been related to both the patrons and the Franciscans. Because of the serious condition of the frescoes, it is difficult to discuss Giotto's style in the chapel, although the frescoes show signs of his typical interest in controlled naturalism and psychological penetration. The Peruzzi Chapel was especially renowned during Renaissance times. Giotto's compositions influenced Masaccio's Cappella Brancacci, and Michelangelo is known to have studied the frescoes.

Giotto's paintings in the lance-shaped chapel are believed to have had a major influence on Michelangelo, who was born nearly 140 years after Giotto died and who painted the Sistine Chapel in the early 1500s. [4] |

|

The Bardi Chapel and the Peruzzi Chapel The Bardi Chapel and the Peruzzi Chapel

in Santa Croce, Florence |

|

|

|

| |

|

Frescoes in the Peruzzi Chapel

|

|

|

Scenes from the Life of St John the Baptist

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annunciation to Zacharias |

|

Birth and Naming of the Baptist |

|

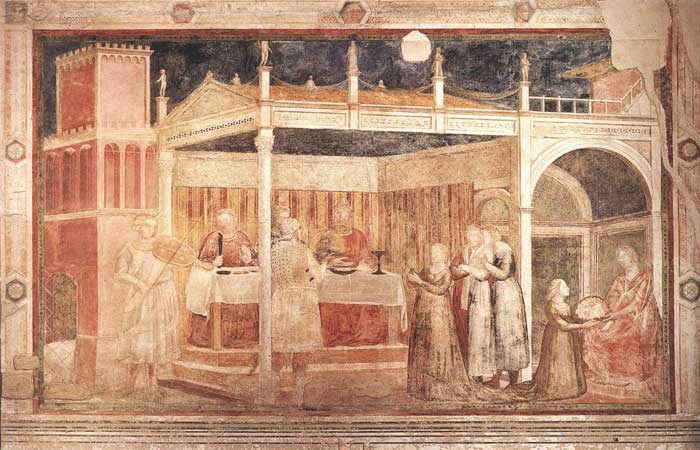

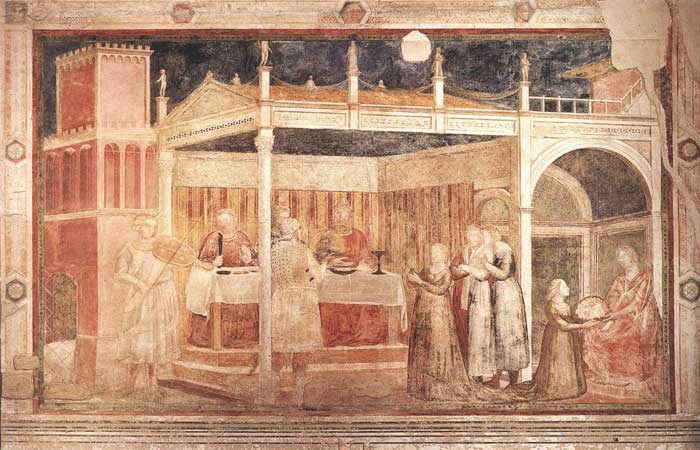

Feast of Herod |

| |

|

|

|

|

Scenes from the Life of St John the Evangelist

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

St John on Patmos |

|

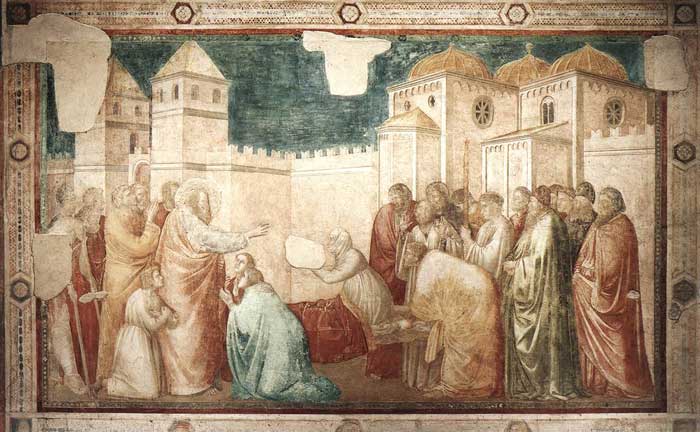

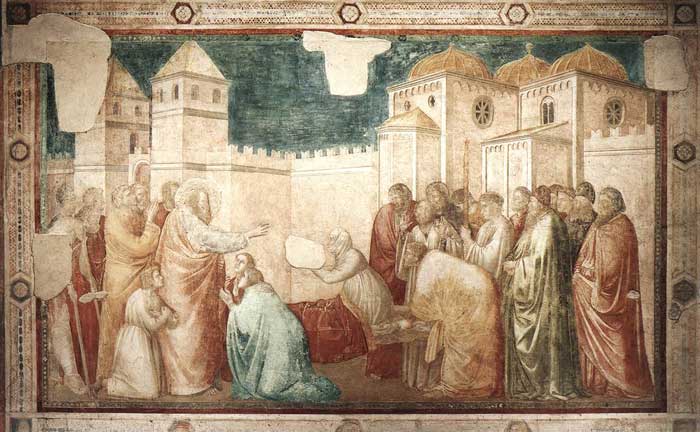

Raising of Drusiana |

|

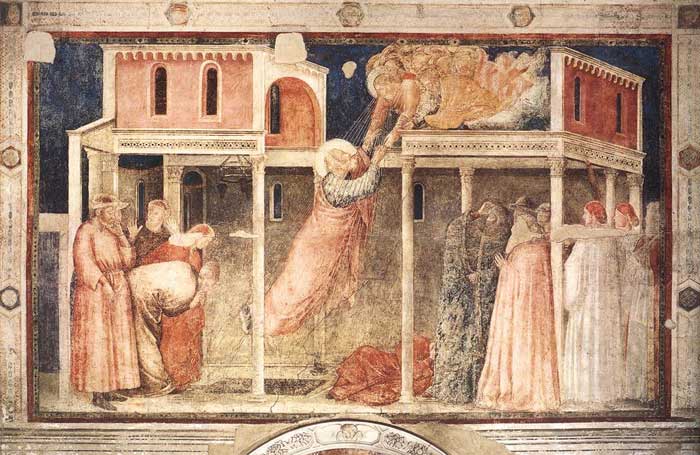

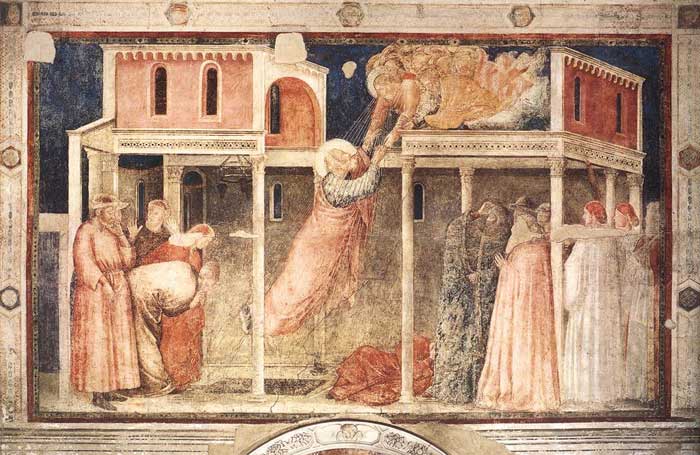

Ascension of the Evangelist |

| |

|

|

|

|

Frescoes in the Peruzzi Chapel | Scenes from the Life of St John the Baptist

|

|

|

Annunciation to Zacharias

|

|

Giotto, Annunciation to Zacharias, 1320, fresco, 280 x 450 cm, Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence |

|

| Zachariah shrinks back before the angel, who prophesies the birth of a son. The musicians on one side, and the women on the other, do not seem to notice any of this. The depiction of the women in particular reveals a change in the way figures are fashioned compared to the Arena Chapel. Although comparable in volume, these women move in a more lithesome fashion.

Giotto has also further developed the depiction of space. Thus the buildings disappear behind the painted frame of the lunette, creating the impression that the view has been truncated. |

| |

|

|

Birth and Naming of the Baptist

|

|

Giotto, Birth and Naming of the Baptist, 1320, fresco, 280 x 450 cm, Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

| This picture field contains two scenes, which Giotto unites by way of the architecture and the domestic environment common to both. On the right, we can see Elizabeth, Johns mother, in labour, and on the left, his father, who is writing his name on a tablet. The world of this house is characterized by women: by women in expensive clothing, who appear considerably more urban than the women in the frescoes at Padua.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Giotto, Feast of Herod, 1320, fresco, 280 x 450 cm, Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

| The banquet takes place in a splendid open hall, decorated with small marble figures. John the Baptist is beheaded at the request of the dancing Salome. In contrast to the festiveness of the scene, Giotto increases the brutality of the events through the gestures, culminating in the encounter between Herod and the henchman, who hands him the severed head as if it were a dish of fare. Even although the surface of the faces is badly damaged, this moment of horror and outrage is still clear: plates, hands, dishes and head form an alarmingly brutal unity, over which soldier and king look at one another. |

|

|

| |

|

|

Frescoes in the Peruzzi Chapel | Scenes from the Life of St John the Evangelist

|

|

|

|

|

Giotto, St John on Patmos, 1320, fresco, 280 x 450 cm, Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

| Peaceful and self-absorbed, the Evangelist sits on the island of Patmos. Only the way he holds his head demonstrates that he is concentrating on his inner visions. At the bottom corners of the lunette angels bind up the wind, in order that calm can be restored. The dragon, which threatens the woman and child, and he who is like the son of man, are the principal figures of the vision of the end of the world and of the second coming of Christ. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Giotto, Raising of Drusiana, 1320, fresco, 280 x 450 cm, Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

| Outside the walls of the city of Ephesus, John the Evangelist resurrects the faithful Drusiana. The firmness and the plasticity of the figures, which harmonize with the architecture, reinforce the dramatic presence of their movements, through which the eye is led to the central event. The tension, which already lies in the encounter between the two groups, is thus heightened further.

Although thronged together, the people still display different reactions, which are obviously dependent on the distance they stand from the actual event, and which range from dumb amazement through to arms thrown up in horror.

We can admire the single well-preserved fragment in the Chapel, the hand of St John the Evangelist to the scene where he resuscitates Drusiana. It is a work of such strength that we think of Masaccio.

|

Ascension of the Evangelist

|

|

|

|

Giotto, Ascension of the Evangelist, 1320, fresco, 280 x 450 cm, Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence |

| |

|

|

Giotto illustrates the miracle of the ascension of John the Evangelist using the astonished, startled reactions of the group at the open tomb. The other group appears blinded and in the grip of a shock wave. The ascension takes place between these two groups: Christ, surrounded by heavenly hosts, appears above the building. He emits golden rays, which envelop the body of the evangelist. They transport the latter to a different sphere and seem like a materialization of the gaze with which Christ looks at John. We are given the impression that the energy, which overcomes gravity, lies more in the meeting of the eyes than in the coincidence of the gestures.

Christ, surrounded by heavenly hosts, appears above the building. He emits golden rays, which envelop the body of the evangelist. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Churches in Florernce |

The Basilica di Santa Croce

Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance painting

[1] The Italian painter, sculptor and architect Giotto di Bondone (known simply as Giotto) was active during the proto-Renaissance era in Padua and Florence. Best known for his humanistic religious frescoes, Giotto - along with the Sienese artist Duccio di Buoninsegna (1255-1319) and Cimabue (1240-1302) - was a key figure in the pre-Renaissance period and is considered one of the founders of fine art painting in Europe. His pictures broke away from the symbolism of Byzantine art and introduced a new naturalism and realism into painting. Although much of his work has been destroyed, his most notable feat was the cycle of fresco paintings in the Cappella degli Scrovegni in Padua (Arena Chapel) (1304-13). Other major works include his frescoes on the life of Saint Francis at Assisi, and in the Bardi and Peruzzi Chapels (created after 1320) in the Franciscan church Santa Croce in Florence.

Many of the details of Giotto's life are sketchy and open to controversy, including the date and place of his birth. It is believed that he was born around 1267 in a village called Vespignano, near Florence. His father was a small landowner described as 'a person of good standing' in public records from the time.

Legend has it, the young Giotto was discovered by the renowned Italian painter Cimabue (also known as Benvenuto di Giuseppe) while he was drawing pictures of his father's sheep. Apparently Cimbaue was so impressed he asked the boy's father if he could take him to Florence as an apprentice. However, it is far more probable that Giotto's family were well off enough to move to Florence and send the 12 year old Giotto to Cimbue's studio as an apprentice.

Around a year later Giotto followed Cimabue to Rome where he was introduced to a school of fresco painters, including the famous Pietro Cavallini and the well-known Florentine architect and sculptor Arnolfo di Cambio.

The earliest of Giotto's known works, is believed to be a series of frescos painted on a church at Assisi about the life of St Francis. At a time when realism in art was not yet popular, these frescos were refreshingly realistic and the figures very natural looking. There is some dispute as to whether it is in fact the hand of Giotto, and recent documents have come to light to suggest that the fresco is in fact the work of a group of unnamed proto-Renaissance artists. If this is so, then Giotto's next most celebrated work, the Fresco of Padua, owes much to the naturalism of these painters.

The Scrovegni Chapel in Padua | In about 1305 Giotto painted a series of 38 frescos at the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel in Padua. The frescos illustrate the life of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary, and the figures are emotionally expressive and realistic looking. Although Giotto specialized in religious art, he broke from the traditions of Byzantine art (which valued the symbolic approach over realism) by infusing his figure drawing with real-life people, poses and expressions. He also introduced an early form of linear perspective into his painting. Although other artists like Pietro Cavallini had started working in this style, Giotto took it much further and set a new standard for figure painting. The art historian and writer Giorgio Vasari, a biographer of Giotto, wrote many stories about the latter's mastery of drawing. One story told how Pope Boniface VIII sent a messenger to Giotto to request samples of his work. As a response, Giotto dipped his brush into red paint and in one continuous stroke painted a perfect circle. He told the messenger to take the circle back to the Pope and that it's worth would be recognised. When the pope received the circle, according to Vasari, he 'instantly perceived that Giotto surpassed all other painters of his time'.

Giotto's reputation as a painter quickly grew, as did his commissions. By 1301 documents show he owned several large estates in Florence (apparently he was a good saver!) and that his workshop had become a leading studio in Italy. But in spite of his fame and demand for his services, no painting survives to this day that is documented by him. There is a certain measure of agreement that Giotto painted frescos at four chapels at the Sta Croce in Florence and the Bardi Chapel. Some of the frescos are in bad condition, as they were whitewashed in the 18th century, but despite this, remain impressive to this day. Several panel paintings on the Stefaneschi Altarpiece at the Vatican bear Giotto's signature, but it believed that this is just a trademark confirming it came from his workshop, rather than a signature of his personal work. On the other hand, the Ognissanti Madonna, c.1315 (Uffizi Gallery) is not signed, but the work is such a grandiose spectacular that it is universally accepted as Giotto's.

Sometime between 1303 and 1310 Giotto executed his most influential work, the painting of a series of 37 scenes at the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Famous panels in the series include The Adoration of the Magi, in which a comet-like Star of Bethlehem streaks across the sky, and the Flight from Egypt. The 19th century English critic John Ruskin said of Giotto's realism 'He painted the Madonna and St. Joseph and the Christ, yes, by all means ... but essentially Mamma, Papa and Baby'. In 1311 Giotto returned to Florence where he executed a work of mosaic art for the facade of the old St. Peter's Basilica and now lost except for some fragments. Remaining frescos from his later years show that Giotto's style had become more ornate, which perhaps reflected the new International Gothic style, which was emerging in Europe.

Revered by this time - even by the more conservative Sienese School of painting - as one of the great new innovative artists, Giotto was honored with the title of Magnus Magister (Great Master) in 1334 by the city of Florence and was appointed city architect and superintendent of public works. During this time he designed the famous campanile (bell tower) on St Peters Square, but died before the work was completed. He last known completed work is the decoration of Podestà Chapel in the Bargello, Florence.

Giotto died in January 1337, but there is some controversy over the exact location of his grave. In 1970, bones were discovered underneath the paving of the Church of Santa Reparta (where his biographer claims he was buried). Forensic examination confirms that they were the bones of a painter (a range of chemicals including arsenic and lead, both commonly found in paint, were discovered in the bones). The front teeth were worn in such as way as to be consistent with holding a brush between the teeth. A reconstruction of the skeleton shows a man with a very large head, large crooked nose and one eye more prominent than the other. The bones were of a small man, only about 4 foot tall who suffered from a form of dwarfism. This would be consistent with a picture in one of the frescos at the church of Santa Croce of a dwarf-like figure which is supposed to be a self portrait of Giotto. His biographer, who was a friend of Giotto, says 'there was no uglier man in the city of Florence'. The body was reburied with honour near the grave of the Renaissance architect Filippo Brunelleschi.

Although Giotto lacked technical knowledge of anatomy and perspective that painters in futures year were to learn, he had grasped something far more important. He grasped human emotion, and was able to portray this is a powerful and meaningful way. He managed to convey, stress, soul-searching, grief and joy through his paint brush, and it was this gift he passed onto future masters of Renaissance art such as Mantegna, Botticelli, Michelangelo, Raphael, Leonardo Da Vinci, Giusto de'Menabuoi, Jacopo Avanzi, Titian and Altichiero. Italian painter Cennino Cennini wrote in about 1400 that `Giotto translated the art of painting from Greek to Latin.'

[2] The Cambridge companion to Giotto, Giotto, By Anne Derbes, Mark Sandona.

|

[3] "We have uncovered a secret Giotto," said Isabella Lapi Ballerini, head of Florence's Opificio delle Pietre Dure, one of the world's most prestigious art restoration laboratories.

In 2009, more than a dozen restorers and researchers began an ambitious project of "non-invasive diagnostics" to ascertain the condition of the 12-meter-high chapel, which Giotto painted in about 1320.

The aim of the study, partly funded by a grant from the Getty Foundation in Los Angeles, was to gather information on the 170 square meter (1,830 square feet) chapel to use as a road map and "hospital chart" for a future restoration. During the project, which lasted four months, restorers working on three stories of steel scaffolding noted that while viewing the paintings under ultra-violet light, they were able see amazing details not visible to the naked eye. "It was something really astonishing," said Cecilia Frosinini, co-coordinator of the project that studied the scenes in the lives of John the Baptist and John the Evangelist.

"We knew we could get some very interesting results from our scientific diagnostics but when we looked under ultra-violet light, all of a sudden all these very faint paintings that were ruined by old restorations took on a new life," she said, pointing to one scene while donning protective eye wear. (Reuters)

[4] Giotto's paintings in the lance-shaped chapel are believed to have had a major influence on Michelangelo, who was born nearly 140 years after Giotto died and who painted the Sistine Chapel in the early 1500s. Today's restorers are seeing the details Michelangelo saw when he admired the paintings by Giotto, considered one of the artists who sowed the seeds for the Italian Renaissance. "The scenes are again three dimensional ... we were able to see all the chiaroscuro effects," she said. "There were bodies under the garments ... they became three dimensional, you could see the folds of the garments, the expressions of the faces." The Peruzzi Chapel was immortalized in E.M. Forster's "Room with a View," in the scene where the young Lucy Honeychurch is shown the Giottos by George Emerson, her future husband. "It is the Giottos that I want to see, if you kindly tell me where they are," Lucy says. Forster continues: "The son nodded. With a look of somber satisfaction, he led the way to the Peruzzi Chapel." Commissioned by the noble Peruzzi family, it was whitewashed in the early 1700s to make way for a new chapel design. But when restorers removed the white paint in 1840, they weren't exactly delicate. They used the techniques of their times, including harsh solvents and steel wool pads that blunted and homogenized the paintings, leaving them looking traumatized. The 19th century "restorers" painted the parts of the Giottos that had been damaged, adding their own brushstrokes to highlight what was no longer visible from the ground. In 1958, a restoration removed what the 19th century restorers added, leaving what remained of the original Giottos and what visitors to the church see today with their naked eyes. PAINTED "A SECCO" Even though they are often referred to as frescoes, the Peruzzi scenes were actually painted "a secco," or on dry plaster, unlike his famous frescos in the Bardi Chapel, which is also in Santa Croce, or his works in St Francis in Assisi. He painted the Peruzzi Chapel toward the end of his life and some experts believe he was striving for a different effect than he achieved with the fresco technique, in which the painting is done while the plaster is still wet. "It allowed him to obtain something more rich in terms of colors, of decorations," Frosinini said. "But over time, dry painting is very fragile," she said. Even after the 1958 restoration removed the "non-Giotto" parts added by 19th century "restorers," the paintings were left faint and anemic, like a patient who had never fully healed. But they come to life under ultra-violet light. In the scene where God is accepting John the Evangelist into heaven, the wrinkles in John's forehead, the threads of his beard, the whites of his eyes and God's welcoming gaze appear like fleeting but powerful visions. Unfortunately, they will remain fleeting forever. The lush details are only visible when they are bathed in ultra-violet light and subjecting them to such constant bombardment would be not only impractical but harmful. The only way to share the discovery with the general public would be with a massive — and expensive — project to allow visitors to enjoy a virtual chapel on computer screens. "I am fully aware that it is impossible to share the same kind of surprise and emotional feeling that we have when we are here in the dark and all of a sudden these images come back to life," Frosinini said. "So I just hope we can find enough funds to have a complete ultra-violet mapping of the whole chapel in order to build some kind of virtual software to share all that we have discovered with the general public," she said. (Philip Pullella, Reuters)

|

Podere Santa Pia is a very nice holiday home situated in the green hills of the Maremma near the tiny medieval town of Cinigiano. The area is wine zone of D.O.C Montecucco and Collemassari, the farm is an ideal spot to spend a pleasant and relaxing holiday. The central location of the holiday home allows you to visit the nearby beautiful villages Montalcino, Sant'Antimo, Pienza, S. Quirico d'Orcia and to the south Saturnia and Sorano - known for its beautiful Sasso Leopoldo. And the sea is 38km away in Marina di Grosseto.

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. |

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

|

View from Podere Santa Pia

on the coast and Corsica |

|

|

|

|

|

Pienza |

|

Montalcino |

|

San Quirico d'Orcia

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sant'Antimo, between Santa Pia and Montalcino |

|

Sansepolcro |

|

The towers of San Gimignano |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia is embedded in the tranquility of the Tuscan country and let you enjoy great views of the Maremma and the island Monte Christo. Although this is off the beaten track it is the ideal choice for those seeking a peaceful, uncontaminated environment.

Situated in panoramic position, overlooking vineyards and olive trees, Santa Pia features incredible sunsets...

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Renaissance Art

The word 'Renaissance' is a French term first coined in the 19th century to describe the intellectual and artistic revival, inspired by a renewed study of Classical literature and art, which began in Italy in the early 14th century and reached its culmination in the early 16th century, having spread in the meantime to other parts of Europe. The equivalent Italian term is Rinascimento. The concept enshrined in the word 'Renaissance' is actually one of rebirth rather than revival and carries with it the loaded, and absolutely discredited, argument that the Middle Ages was a dead period intellectually and artistically. Such a view effectively renders Byzantine, Romanesque and Gothic art as being without aesthetic value. Though this position is untenable, the term 'Renaissance' is useful in so far as it denotes a view that was held by contemporary, especially Italian, thinkers and because the period covered by the term, in the leading artistic centres of Italy, exhibits a growing preoccupation with a coherent set of values based on antique Classical models.

It was Petrarch (1304-74) who first evoked the complementary images of the prevailing darkness of the Middle Ages, when the intellectual achievements of the Classical world had been forgotten, and the subsequent illumination of his own period following their rediscovery by scholars such as himself. Thus, the renewal of interest in the antique was first and foremost an intellectual and literary revival. The importance of Classical texts to the development of the visual arts was their inherent view of a world with man at the centre. Also, references to the arts in the antique world revealed that artists were valued for their ability to represent nature with great fidelity and that, furthermore, they enjoyed a higher status than their medieval counterparts. Thus, the beginnings of Renaissance art in Italy should be recognizable by seeking out not only those artists who adopted motifs or borrowed models from antiquity, but also those who sought to represent the human figure and the material world more naturalistically than had their predecessors.

Until the 20th century the generally accepted model for the development of the artistic Renaissance was that constructed by Vasari, writing in 1550. He gave to Giotto the credit for the rebirth of art after centuries of barbarism and structured his chronological model like the ages of man, with Giotto and his immediate heirs as representing the infancy of art; Masaccio, Brunelleschi, Donatello and Ghiberti as the experimental youth; and Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo as the perfected maturity. Although notions of rebirth (and the previous death the term implies) and artistic progress are now rejected, and although it is recognized that Vasari was above all a Florentine writer structuring history in Florentine terms in order to set the scene for his friend and idol, the Florentine all-round artist, Michelangelo, Vasari's account is useful in that it does reflect what is a perceptible movement away from an art based on conventionalized representations of a supernatural reality towards an increasing technical expertise (in which Florence mostly led the way) in the representation of a visually convincing and rationally ordered natural world. The subject matter was still preponderantly sacred, but Christ and the saints were now conceived with more corporeality, and increasingly not in an ethereal Heaven, but at the centre of the physical world.

If we accept Vasari's implication that Giotto was a Renaissance artist we should also be aware that he was in fact preceded by a non-Florentine, the sculptor, Nicola Pisano. Both artists imbue the human figure with a new power, dignity and gravity; and, furthermore, Pisano quotes directly from antique Roman sarcophagi, thus fulfilling the second requirement for a true Renaissance artist. Unfortunately, the following century does not present an ordered development from the achievements of these two figures and it is more usual today to agree with Alberti (writing in 1435) that the artistic Renaissance of Italy actually began in Florence in the early 15th century. The strength of this model is that what follows in Florence and in all those centres affected by Florentine art, presents a largely coherent artistic development throughout the century.

Brunelleschi, placed by Alberti in the vanguard of the new art, was the first architect to go beyond the arbitrary usage of the vocabulary (i.e. the recognizable motifs) of Classical buildings towards a perception of the underlying grammar (the order and harmony created by the rational proportional relationships of part to part and part to whole). Brunelleschi also seems to have made the earliest experiments in single point linear perspective and may have advised Masaccio in its possibilities for constructing a rationally ordered picture space. Certainly the fictive architecture in Masaccio's Trinity (c. 1428, Florence, Sta Maria Novella) is Brunelleschian. The earliest surviving use of linear perspective, however, is in Donatello's St. George and the Dragon relief (c. 1417, Florence, Or San Michele). Of the sculptors that looked towards Classical models, Donatello, like Brunelleschi with his architecture, was the one that most clearly understood the underlying spirit of Classicism. Throughout the 15th century (today usually designated the 'Early Renaissance'), Florentine artists were at the forefront of investigations into the representation of the natural world. To some, one particular area of investigation or another might take precedence: to Uccello it was the underlying geometry of form and the organizational possibilities of perspective and to Antonio Pollaiuolo, anatomy. Another hallmark of the Renaissance is that although the overwhelming majority of commissions were still sacred there was also, as the century progressed, a growth in lay patronage requiring portraits and other secular images, particularly those dealing with themes from Classical mythology.

The first quarter of the 16th century is generally termed the 'High Renaissance'. It is the period when the leading artists had sufficient technical expertise to achieve virtually any naturalistic effect they wished, coupled with a controlling, Classically-based intelligence which imposed visual harmony and compositional balance while eliminating gratuitous detail. Although most of the leading protagonists were Florentine - Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael - the centre of production had shifted to Rome (where these three men worked) and to Venice, where Bellini, Giorgione and Titian were creating their own High Renaissance style. The most important architect of the High Renaissance, whose buildings were the first to be considered as having fully recaptured the grandeur of ancient Rome, was Bramante.

It was not until this period that Italian Renaissance ideals began to spread in a significant way north of the Alps, Durer being the first northern artist to fully assimilate the ideals of the Renaissance into his work. Increasingly, from the 16th century onwards, northern artists would finish their artistic education by visiting Italy. Foreign rulers and states also sought to buy in Italian artists, but from the 1520s Mannerism had supplanted the High Renaissance style and thus in France, for example, direct Italian influence in the 16th century is essentially Mannerist (e.g. Francis I's School of Fontainebleau). Nevertheless, Mannerist art is inconceivable without the Classical ideals of the Renaissance (whether to flout deliberately or to exaggerate) and those ideals continued to exert a powerful influence on artists, alongside the art of Classical antiquity, as the supreme exemplar up until the second half of the 19th century and the advent of Realism and Impressionism.

[From The Bulfinch Guide to Art History: A Comprehensive Survey and Dictionary of Western Art and Architecture, Shearer West (Editor), Bulfinch Pr (September 1996)].

|

Giotto, Masaccio and others: fresco cycles in Florence

The frescoes depicting religious stories in medieval churches were defined as the Biblia pauperum, the poor person’s Bible, because of the scope they offered for teaching stories concerning God and the saints to a largely illiterate population. But apart from their functional didactic value, they were also one of the areas in which the finest artists of the past, including the likes of Giotto, Masaccio and Michelangelo, tested their skills.

Two of Florence’s most well-known fresco cycles are to be found in the Bardi and Peruzzi Chapels in Santa Croce. They were painted by Giotto and his workshop and depict scenes from the Life of Saint Francis (Bardi Chapel) and the Lives of Saint John the Baptist and Saint John the Evangelist (Peruzzi Chapel). The church also houses some other very interesting cycles: the Legend of the True Cross in the sanctuary is by Agnolo Gaddi, as are the scenes from the Lives of Saints Antony Abbot, John the Baptist and John the Evangelist in the Castellani Chapel.

The stories told on the walls generally concern the saint to which the church is dedicated, the religious order of the church or the families who were patrons of the chapels (in which case the name of the chosen saint often coincided with that of the patron). And so, for instance, the frescoes in Santa Croce depict scenes from the Life of Saint Francis, the frescoes by Andrea del Bonaiuto (c.1367–69) in the Spanish Chapel in Santa Maria Novella develop the theme of the struggle of the Dominicans against Christian heresy, while the chapel of the family of Filippo Strozzi in the same church was frescoed by Filippino Lippi with scenes from the Life of Saint Philip (1494–1502).

However, the frescoes are not just interesting for their themes: they are often set in the city of the time, and show the buildings, clothes and furniture of the age, offering what amounts to a kind of postcard of the past. This is the case of Ghirlandaio’s frescoes (1485–90) in the Tornabuoni Chapel in Santa Maria Novella, where one can admire the fine clothes of the noblewomen portrayed and the interiors of luxurious 15th-century homes.

But the fresco cycles are above all a testing ground for the representation of figures in space and the application of perspective. This problem, which Giotto tackled by developing a kind of empirical perspective, was solved by Masaccio in his cycle in the Brancacci Chapel in the Chiesa del Carmine (1424–28), and with such authoritativeness that it was studied by later artists, first and foremost Michelangelo.

(

From Apt - Agenzia per il Turismo di Firenze (Florence Official Tourist Office) |

|

|