| |

|

| The Basilica di Santa Croce is the principal Franciscan church in Florence. It is situated on the Piazza di Santa Croce. The site, when first chosen, was in marshland outside the city walls. Legend says that Santa Croce was founded by St Francis himself. It is the burial place of some of the most illustrious Italians, such as Michelangelo, Galileo, Machiavelli, Foscolo, Gentile and Rossini.

Its most notable features are its sixteen chapels, many of them decorated with frescoes by Giotto and his pupils, and its tombs and cenotaphs.

The frescoes depicting religious stories in medieval churches were defined as the Biblia pauperum, the poor person’s Bible, because of the scope they offered for teaching stories concerning God and the saints to a largely illiterate population. But apart from their functional didactic value, they were also one of the areas in which the finest artists of the past, including the likes of Giotto, Masaccio and Michelangelo, tested their skills.

Two of Florence’s most well-known fresco cycles are to be found in the Bardi and Peruzzi Chapels in Santa Croce. They were painted by Giotto and his workshop and depict scenes from the Life of Saint Francis (Bardi Chapel) and the Lives of Saint John the Baptist and Saint John the Evangelist (Peruzzi Chapel). The church also houses some other very interesting cycles: the Legend of the True Cross in the sanctuary is by Agnolo Gaddi, as are the scenes from the Lives of Saints Antony Abbot, John the Baptist and John the Evangelist in the Castellani Chapel.

The stories told on the walls generally concern the saint to which the church is dedicated, the religious order of the church or the families who were patrons of the chapels (in which case the name of the chosen saint often coincided with that of the patron). And so, for instance, the frescoes in Santa Croce depict scenes from the Life of Saint Francis, the frescoes by Andrea del Bonaiuto (c.1367–69) in the Spanish Chapel in Santa Maria Novella develop the theme of the struggle of the Dominicans against Christian heresy, while the chapel of the family of Filippo Strozzi in the same church was frescoed by Filippino Lippi with scenes from the Life of Saint Philip (1494–1502).

However, the frescoes are not just interesting for their themes: they are often set in the city of the time, and show the buildings, clothes and furniture of the age, offering what amounts to a kind of postcard of the past. This is the case of Ghirlandaio’s frescoes (1485–90) in the Tornabuoni Chapel in Santa Maria Novella, where one can admire the fine clothes of the noblewomen portrayed and the interiors of luxurious 15th-century homes.

But the fresco cycles are above all a testing ground for the representation of figures in space and the application of perspective. This problem, which Giotto tackled by developing a kind of empirical perspective, was solved by Masaccio in his cycle in the Brancacci Chapel in the Chiesa del Carmine (1424–28), and with such authoritativeness that it was studied by later artists, first and foremost Michelangelo.

|

At the end of 1313, Giotto was back in Florence and was once more working in a Franciscan church, in the great Minorite church of Santa Croce, for which he was to continue creating works right up until the end of his life. According to a statement made by the Florentine artist Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378—1455), Giotto painted four of the chapels here. Several noble Florentine families are also said to have commissioned panel paintings from him, with which they endowed the altars in Santa Croce. But only two chapels and one altarpiece which can confidently be attributed to Giotto have survived the ravages of time - the Peruzzi and Bardi chapels.

The two chapels, which Giotto decorated for the two Florentine banking dynasties, lies next to one another in the Franciscan church. On the left, we can see into the Bardi Chapel and can make out the vault with its representations of the Franciscan virtues; to the right, in the Peruzzi chapel we can see the scenes from the life of St John the Evangelist. It is clear that Giotto composed these latter paintings in relation to the view from outside the chapel. Giotto painted a fresco of the Stigmatization of St Francis on the outside wall of the Bardi Chapel over the arch, which identifies the dedication of the chapel from a distance and at the same time provides the Franciscans with a large-scale image within the church itself of a defining moment in the life of their patron and founder.

The Bardi Chapel is of particular interest as it depicts the life of St. Francis, following a similar iconography to the frescoes in the Upper Church at Assisi, dating from 20–30 years earlier. A comparison makes apparent the greater attention given by Giotto to expression in the human figures and the simpler, better-integrated architectural forms. Giotto represents only 7 scenes from the saint's life here, and the narrative is arranged somewhat unusually. The story starts on the upper left wall with St. Francis Renounces his Father. It continues across the chapel to the upper right wall with the Approval of the Franciscan Rule, moves down the right wall to the Trial by Fire, across the chapel again to the left wall for the Appearance at Arles, down the left wall to the Death of St. Francis, and across once more to the posthumous Visions of Fra Agostino and the Bishop of Assisi. The Stigmatization of St. Francis, which chronologically belongs between the Appearance at Arles and the Death, is located outside the chapel, above the entrance arch. This arrangement encourages viewers to link scenes together: to pair frescoes across the chapel space or relate triads of frescoes along each wall. These linkings suggest meaningful symbolic relationships between different events in St. Francis's life.

|

|

The Bardi Chapel and the Peruzzi Chapel The Bardi Chapel and the Peruzzi Chapel

in Santa Croce, Florence

|

|

Giotto, Vision of the Ascension of St Francis(detail), c. 1325, fresco, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence |

|

|

|

| |

|

Frescoes in the Bardi Chapel

|

|

|

Giotto also received the commission for the second surviving chapel in the Franciscan church of Santa Croce in Florence from a banker. The donor Ridolfo de' Bardi and his brother jointly inherited their father's banking house and commercial interests. This involved maintaining a good relationship with the powers who determined the politics of the day - with the pope, with the Neapolitan ruling house of Anjou, and with the Guelph party. He was able to go on cultivating this highly effective mixture of faith, politics and money for the next three decades until his house went bankrupt in the 1340s.

The Bardi family chapel is situated to the right of the choir, which means that it is the first chapel of the southern transept, and dedicated to St. Francis. As was the case with the neighboring Peruzzi Chapel, these frescoes were also painted over in the 18th century, rediscovered in the 19th century, and reworked. During their restoration in the middle of our own century, all reworked areas were removed and the ruined parts sealed with plaster. For this reason, some of the frescoes have empty spaces, although the actual painting is considerably better preserved here than in the Peruzzi Chapel, since Giotto went back to working with fresh plaster here.

As in the Peruzzi chapel, three frescoes framed by ornamental bands decorate each wall. But unlike in the former, these are dedicated to just the one saint, St. Francis. The Renunciation of Worldly Goods and the Confirmation of the Rule are situated in the lunettes. In the middle register the Apparition at Arles and the Trial by Fire before the Sultan are depicted. The Death of St. Francis and Inspection of the Stigmata and the Apparition at Aries can be seen at eye level. Above the entrance to the chapel the Stigmatisation is portrayed, as it were, as a summation of the life of the saint. The seraphim from whom Francis receives the stigmata here appears — unlike at Assisi or in the panel in the Musée du Louvre — as the crucified Christ.

While the St Francis in the paintings in the Upper Church at Assisi wears a beard, Giotto depicts him without one here, as in the vault frescoes in the Lower Church. This manifestation of the saint, favoured by the order since 1316, must have been particularly agreeable to a banker, since it no longer expressed the original significance of personal poverty.

Unlike the Peruzzi Chapel, the construction of the architecture portrayed in the frescoes is here based on a viewpoint within the chapel. The perspective of the architectural structures in the paintings changes with great logical consistency — the higher the register, the greater the foreshortening from below. This only increases the impression of fluidity between real and painted space.

|

Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stigmatisation of Saint Francis |

|

Renunciation of Wordly Goods |

|

Apparition at Arles |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Death and Ascension of St Francis |

|

Confirmation of the Rule |

|

Ascension of the Evangelist |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vision of the Ascension of St Francis |

|

|

|

|

Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis | Stigmatisation of Saint Francis

|

|

Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis, Stigmatisation of Saint Francis, 1325, fresco, 390 x 370 cm, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

| The Stigmatisation of Saint Francis appears above the entrance to the chapel. Being marked with the stigmata is the high point in the saint's life. They mark him out for all to see as one of Christ's successors. The seraphim from whom Francis receives the stigmata here appears — unlike at Assisi or in the panel in the Musee du Louvre — as the crucified Christ. Fine golden rays emanating from Christ's wounds lead to St. Francis. In this representation the saint almost appears startled. He is in this way turned both towards the faithful and towards Christ. |

|

|

|

Renunciation of Wordly Goods

|

|

Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis, Renunciation of Wordly Goods, 1325, fresco, 280 x 450 cm, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

The scene Renunciation of Wordly Goods is situated in the lunette of the wall left to the entrance of the chapel.

The clearly articulated palace building is set obliquely within the field of the lunette. This creates great tension, appropriate to the confrontation between St. Francis and his infuriated father. Giotto also uses the reactions of the individual figures to demonstrate the outrageousness of the saints public decision to renounce all his worldly goods.

With the palace in the rear of the Renunciation of Worldly Goods, Giotto has created a complex, active, multilayered, and expansive space that allows and encourages him to break with the frieze-like arrangement of his figures in all the prior compositions. By liberating his architectural setting from the limits of its frame, he sets his figures free as well.[2] |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

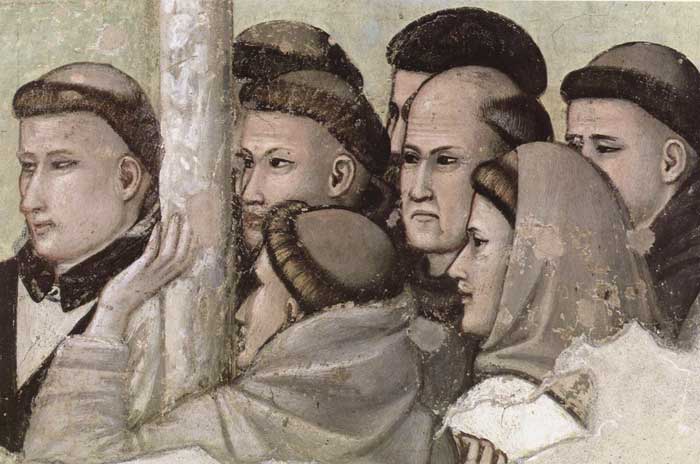

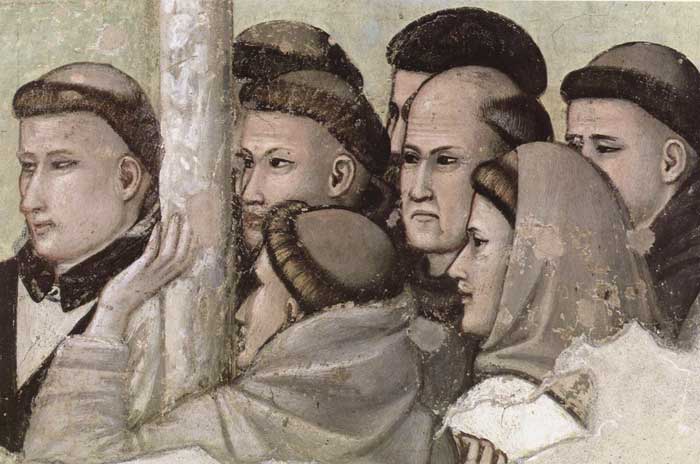

Giotto, Apparition at Arles, c. 1325, fresco, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

This scene is situated at the middle register on the wall left to the entrance of the chapel.

During a sermon delivered by the Franciscan brother Augustine, St. Francis appeared in support of his words. He blesses the monks and so strengthens them in their faith. The architecture is completely free of Gothic decoration, making the vividness of the faces is all the more striking.

|

| |

|

|

Death and Ascension of St Francis

|

|

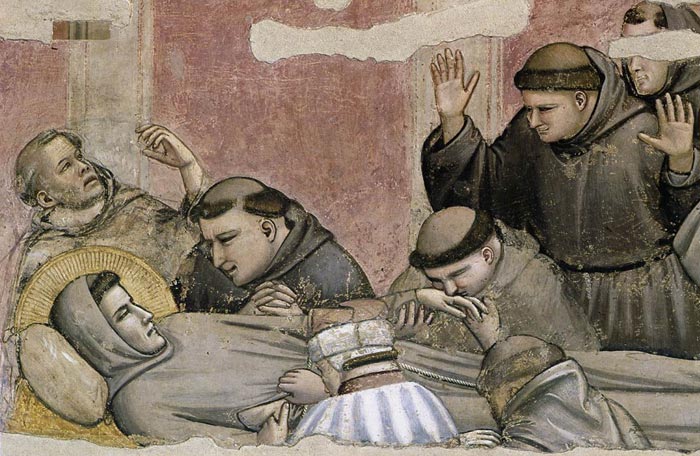

Giotto, Death and Ascension of St Francis, c. 1325, fresco, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

| This scene is situated at eye level on the wall left to the entrance of the chapel.

In an extremely compressed space, St. Francis' disciples have gathered for his funeral. One of them notices that the saints soul is being carried heavenward by angels. While one monk kisses the stigmata, a disbelieving nobleman examines the wound in St. Francis' side.

The remarkable foreshortening of the figure of the friar kissing the saint's hands is reminiscent of the foreshortening used in the sleeping soldier in the Resurrection of the Upper Church of San Francesco at Assisi.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Giotto di Bondone, Transito di Francesco, restauro, volto post pulitura in attesa del ritocco pittorico , cappella Bardi, basilica di Santa Croce, Firenze

|

|

Giotto di Bondone, Esequie di san Francesco (particolare), Cappella Bardi, Basilica di Santa Croce, Firenze

|

|

Giotto di Bondone, Morte e verifica delle stimmate di san Francesco d'Assisi (particolare san Francesco), 1317-1325, Cappella Bardi, Basilica di Santa Croce, Firenze

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Giotto, Confirmation of the Rule, c. 1325, fresco, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

| This scene is situated in the lunette of the wall right to the entrance of the chapel.

In this representation the simple architecture is placed parallel to the picture plane of the lunette. This creates a strong and clearly articulated composition. Francis kneels with his companions before Pope Honorius III, who approves the first rule. We notice the careful arrangement of the friars behind St Francis.

|

|

|

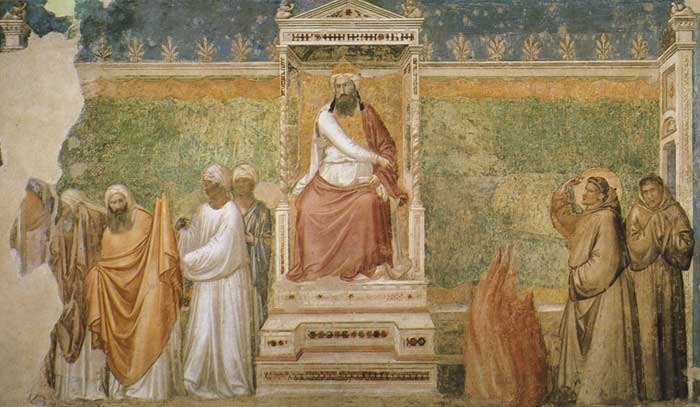

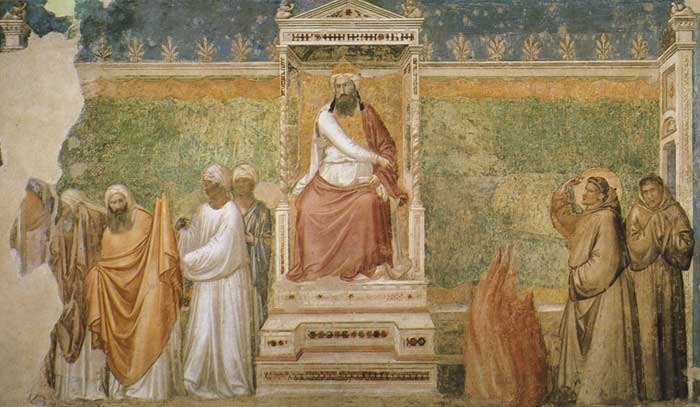

St Francis before the Sultan (Trial by Fire)

|

|

Giotto,c. 1325, St Francis before the Sultan (Trial by Fire), fresco, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

This scene is situated at the middle register on the wall right to the entrance of the chapel.

The sultan is enthroned in the centre of the picture and is referring his priests to the fire. Unlike Francis, the latter do not wish to undergo the trial by fire, and they steal away. In this fresco the faces of the foreigners are painted particularly vividly. The coloured faces lead us to conclude that Nubians or Ethiopians were present in Florence.

The faces of the foreigners are painted particularly vividly. The coloured faces lead us to conclude that Nubians or Ethiopians were present in Florence.

|

Vision of the Ascension of St Francis

|

|

Giotto, Vision of the Ascension of St Francis, c. 1325, fresco, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

The Vision of the Ascension of St Francis is situated at eye level on the wall right to the entrance of the chapel.

A major restoration operation on Giotto ’s frescoed Stories of St. Francis in the Bardi Chapel of Santa Croce in Florence is revealing new details and restoring previously unseen legibility to the Florentine master’s masterpiece. The project is led by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure (OPD) and the Opera di Santa Croce, with support from the Fondazione CR Firenze and the ARPAI Association, and is directed by Cristina Acidini (president of the Opera di Santa Croce) and Emanuela Daffra (superintendent of the OPD). [3]

The renewed freshness and refinement of some details show us the effects of realism and spatial complexity of Giotto's paintings. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Giotto di Bondone, Visioni dell'ascensione di san Francesco (particolare), scena delle Storie di san Francesco, cappella Bardi, basilica di Santa Croce, Firenze

|

|

Giotto di Bondone, Visioni dell'ascensione di san Francesco, restauro, volto post pulitura in attesa del ritocco pittorico , cappella Bardi, basilica di Santa Croce, Firenze

|

|

La restauratrice Maria Rosa Lanfranchi al lavoro sul «Transito di Francesco» nella Cappella Bardi della Basilica di Santa Croce di Firenze

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Florence, Santa Croce, Giotto, Restoration of the frescoes

The frescoes in the Bardi Chapel have an eventful history and still bear the traces of it.Both Ghiberti and Vasari claimed that in the eighteenth century the basilica was in a very poor condition, partly as a result of the infiltrations and floods that had struck Santa Croce several times. In the eighteenth century, the frescoes were covered with a scialbo, a layer of white lime.In 1812, the tomb of the architect Giuseppe Salvetti was built into the left wall, and in 1818, opposite it, that of Niccolò Gaspero Paoletti.In the mid-nineteenth century, Giotto's frescoes were rediscovered: the white lime layer was sanded away and the cenotaphs were removed and transferred to the Salviati chapel. The paintings were restored by Gaetano Bianchi, who restored the damaged or completely lost parts of the frescoes. This 1853 intervention is commemorated by an inscription to the right of the altar. The restoration, in keeping with the philosophy of the time, included additions in "style. A century later, between 1957 and 1958, the subsequent restoration aimed at restoring a more authentic Giotto by removing the pictorial additions.

The very delicate operation was entrusted to Leonetto Tintori, the most famous Italian restorer of frescoes. He carried out this new restoration in 1958-1959, preserving only the original parts. However, he used synthetic, vinyl fixatives in this restoration, and it is with this last intervention, as well as with the damage caused by the 1966 flood, that the recent restoration was confronted. The condition of the frescoes can be seen in some photos that pre-date 1959.In 2022, a new phase in the restoration of the chapel began. The modern, scientific approach tries to remedy the disasters of the past as best as possible. Preceded by and multidisciplinary and non-invasive diagnostic examination, that is, with techniques that do not touch the murals, the most recent rrestoration began in June 2022. The restoration of the chapel was entrusted to Cristina Acidini, President of the Opera di Santa Croce, and Emanuela Daffra, Superintendent of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure.

Giotto, in particular, used a combination of fresco and dry painting techniques, exploiting organic binders, such as egg, to expand the color range and create more intense chiaroscuro effects. The restoration revealed hidden details and lost color fragments, which we can now appreciate thanks to the cleaning carried out. Among the surprises were also an earlier decoration, probably geometric, the discovery of the pontaie holes, that is, the holes for the scaffolding, which thus made it possible to know the exact layout of the structure that Giotto mounted to paint, and then again traces of the sinopites and preparatory drawing. It was also possible to reconstruct the course of the “days” of the tonachino, or the thin layer of plaster on which Giotto and collaborators had spread the colors. Also found were some test brushstrokes of which Giotto used to test how the colors would change after the plaster dried: these brushstrokes would then be concealed by the dry layers of colors, but today they are visible again as these additions have been lost. [3]

Giotto in Santa Croce | De restauratie van de Bardi-kapel in Santa Croce, oktober 2024 - juli 2025

|

|

Giotto di Bondone, San Francesco rinuncia alle vesti davanti al vescovo Guido e al padre Bernardone (particolare), 1317-1325, Cappella Bardi, basilica di Santa Croce, Firenze

|

Churches in Florernce |

The Basilica di Santa Croce

Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance painting

[1] The Italian painter, sculptor and architect Giotto di Bondone (known simply as Giotto) was active during the proto-Renaissance era in Padua and Florence. Best known for his humanistic religious frescoes, Giotto - along with the Sienese artist Duccio di Buoninsegna (1255-1319) and Cimabue (1240-1302) - was a key figure in the pre-Renaissance period and is considered one of the founders of fine art painting in Europe. His pictures broke away from the symbolism of Byzantine art and introduced a new naturalism and realism into painting. Although much of his work has been destroyed, his most notable feat was the cycle of fresco paintings in the Cappella degli Scrovegni in Padua (Arena Chapel) (1304-13). Other major works include his frescoes on the life of Saint Francis at Assisi, and in the Bardi and Peruzzi Chapels (created after 1320) in the Franciscan church Santa Croce in Florence.

"The first of the great personalities in Florentine painting was Giotto. Although he affords no exception to the rule that the great Florentines exploited all the arts in the endeavor to express themselves, he, Giotto, renowned as an architect and sculptor, reputed as wit and versifier, differed from most of his Tuscan successors in having a peculiar aptitude for the essential in painting as an art .

"Well, it was of the power to stimulate the tactile consciousness of the essential, as I have ventured to call it, in the art of painting that Giotto was supreme master. This is his everlasting claim to greatness, and it is this which will make him a source of highest aesthetic delight for a period at least as long as decipherable traces of his handiwork remain on mouldering panel or crumbling wall. For great though he was as a poet, enthralling as a story teller, splendid and majestic as a composer, he was in these qualities superior in degree only, to many of the masters who painted in various parts of Europe during the thousand years that intervened between the decline of antique, and the birth, in his own person, of modem painting. But none of these masters had the power to stimulate the tactile imagination, and, consequently, they never painted a figure which has artistic existence. Their works have value, if at all, as highly elaborate, very intelligible symbols, capable, indeed, of communicating something, but losing all higher value the moment the message is delivered.

"Giotto's paintings, on the contrary, have not only as much power of appealing to the tactile imagination as is possessed by the objects represented human figures in particular but actually more; with the necessary result that to his contemporaries they conveyed a keener sense of reality, of life likeness than the objects themselves! We whose current knowledge of anatomy is greater, who expect more articulation and suppleness in the human figure, who, in short, see much less naively now than Giotto's contemporaries, no longer find his paintings more than life like; but we still feel them to be intensely real in the sense that they powerfully appeal to our tactile imagination, thereby compelling us, as do all things that stimulate our sense of touch while they present themselves to our eyes, to take their existence for granted. And it is only when we can take for granted the existence of the object painted that it can begin to give us pleasure that is genuinely artistic, as separated from the interest we feel in symbols...

"Let us now turn back to Giotto and see in what way he fulfils the first condition of painting as an art, which condition, as we agreed, is somehow to stimulate our tactile imagination. We shall understand this without difficult) if we cover with the same glance two pictures of, nearly the same subject that hang side by side in the Uffizi at Florence, one by 'Cimabue', and the other by Giotto. The difference is striking, but it does not consist so much in a difference of pattern and types, as of realization. In the 'Cimabue' we patiently decipher the lines and colours, and we conclude at last that they were intended to represent a woman seated, men and angels standing by or kneeling. To recognize these representations we have had to make many times the effort that the actual objects would have required, and in consequence our feeling of capacity has not only not been confirmed, but actually put in question. With what sense of relief, of rapidly rising vitality, we turn to the Giotto 1 Our eyes scarcely have had time to light on it before we realize it completely the throne occupying a real space, the Virgin satisfactorily seated upon it, the angels grouped in rows about it. Our tactile imagination is put to play immediately. Our palms and fingers accompany our eyes much more quickly than in presence of real objects, the sensations varying constantly with the various projections represented, as of face, torso, knees; confirming in every way our feeling of capacity for coping with things~ for life, in short. I care little that the picture endowed with the gift of evoking such feelings has faults, that the types represented do not correspond to my ideal of beauty, that the figures are too massive, and almost unarticulated; I forgive them all, because I have much better to do than to dwell upon faults.

"But how does Giotto accomplish this miracle? With the simplest means, with almost rudimentary light and shade, and functional line, he contrives to render, out of all the possible outlines, out of all the possible variations of light and shade that a given figure may have, only those that we must isolate for special attention when we are actually realizing it. This determines his types, his schemes of colour, even his compositions. He aims at types which both in face and figure are simple, large boned, and massive types, that is to say, which in actual life would furnish the most powerful stimulus to the tactile imagination. Obliged to get the utmost out of his rudimentary light and shade, he makes his scheme of colour of the lightest that his contrasts may be of the strongest. In his compositions he aims at clear ness of grouping, so that each important figure may have its desired tactile value. Note in the 'Madonna' we have been looking at, how the shadows compel us to realize every concavity, and the lights every convexity, and how, with the play of the two, under the guidance of line, we realize the significant parts of each figure, whether draped or undraped. Nothing here but has its architectonic reason. Above all, every line is functional; that is to say, charged with purpose. Its existence, its direction, is absolutely determined by the need of rendering the tactile values. Follow any line here, say in the figure of the angel kneeling to the left, and see how it outlines and models, how it enables you to realize the head, the torso, the hips, the legs, the feet, and how its direction, its tension, is always determined by the action. There is not a genuine fragment of Giotto in existence but has these qualities, and to such a degree that the worst treatment has not been able to spoil them. Witness the resurrected frescoes in Santa Croce at Florence!

"The rendering of tactile values once recognized as the most important specifically artistic quality of Giotto's work, and as his personal contribution to the art of painting, we are all the better fitted to appreciate his more obvious though less peculiar merits must add, which would seem far less extraordinary if it were not for the high plane of reality on which Giotto keeps us. Now what is behind this power of raising us to a higher plane of reality but a genius for grasping and communicating real significance? What is it to render the tactile values of an object but to communicate its material significance? A painter who, after generations of mere manufacturers of symbols, illustrations, and allegories, had the power to render the material significance of the objects he painted, must, as a man, have had a profound sense of the significant. No matter, then, what his theme, Giotto feels its real significance and communicates as much of it as the general limitations of his art and of his own skill permit. When the theme is sacred story, it is scarcely necessary to point out with what processional gravity, with what hieratic dignity, with what sacramental intentness he endows it; the eloquence of the greatest critics has here found a darling subject. But let us look a moment at certain of his symbols in the Arena at Padua, at the 'Inconstancy', the 'Injustice', the 'Avarice', for instance. 'What are the significant traits', he seems to have asked himself, 'in the appearance and action of a person under the exclusive domination of one of these vices? Let me paint the person with these traits, and I shall have a figure that perforce must call up the vice in question! So he paints 'Inconstancy' as a woman with a blank face, her arms held out aimlessly, her torso falling backwards, her feet on' the side of a wheel. It makes one giddy to look at her. 'Injustice' is a powerfully built man in the vigour of his years dressed in the costume of a judge, with his left hand clenching the hilt of his sword, and his clawed right hand grasping a double hooked lance. His cruel eye is sternly on the watch, and his attitude is one of alert readiness to spring in all his giant force upon his prey. He sits enthroned on a rock, overtowering the tall waving trees, and below him his underlings are stripping and murdering a wayfarer. 'Avarice' is a homed hag with ears like trumpets. A snake issuing from her mouth curls back and bites her forehead. Her left hand clutches her money bag, as she moves forward stealthily, her right hand ready to shut down on whatever it can grasp. No need to label them: as long as these vices exist, for so long has Giotto extracted and presented their visible significance.

"Still another exemplification of his sense for the significant is furnished by his treatment of action and movement. The grouping, the gestures never fail to be just such as will most rapidly convey the meaning. So with the significant line, the significant light and shade, the significant look up or down, and the significant gesture, with means technically of the simplest, and, be it remembered, with no knowledge of anatomy, Giotto conveys a complete sense of motion such as we get in his Paduan frescoes of the 'Resurrection of the Blessed', of the 'Ascension of our Lord', of the God the rather in the 'Baptism', or the angel in 'Zacharias' Dream'.

"This, then, is Giotto's claim to everlasting appreciation as an artist: that his thoroughgoing sense for the significant in the visible world enabled him so to represent things that we realize his representations more quickly and more completely than we should realize the things themselves, thus giving us that confirmation of our sense of capacity which is so great a source of pleasure."

[From Bernard Berenson, Italian Painters of the Renaissance]

[2] The Cambridge companion to Giotto, Giotto, By Anne Derbes, Mark Sandona.

[3] SOURCE: The restoration of Giotto's frescoed Stories of St. Francis in the Bardi Chapel in Santa Croce |www.finestresullarte.info/en

Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence

|

|

|

|

|

|

Farnese |

|

Chianti region

|

|

Siena, Duomo |

The Basilica di Santa Croce (Basilica of the Holy Cross) is the principal Franciscan church in Florence, Italy, and a minor basilica of the Roman Catholic Church. It is situated on the Piazza di Santa Croce, about 800 metres south east of the Duomo. The site, when first chosen, was in marshland outside the city walls. It is the burial place of some of the most illustrious Italians, such as Michelangelo, Galileo, Machiavelli, Foscolo, Gentile and Rossini, thus it is known also as the Temple of the Italian Glories (Tempio dell'Itale Glorie).

In 1966, the Arno River flooded much of Florence, including Santa Croce. The water entered the church bringing mud, pollution and heating oil. The damage to buildings and art treasures was severe, taking several decades to repair.

Santa Croce was the first populated area to be overflowed by the flood. This area remained under the water longer compared to the others because it's lower with respect to the river. The Arno river completely filled the Cloister, it penetrated into the crypt, it disrupted the tombs of the Church. The works of removing the mud and the rubble took about two months. But the damages didn't finish here: the Franciscan fathers and those in charge of the Belle Arti saw the most devastating reality: the Crucifix by Cimabue, located in the Museum inside the big Franciscan refectory, was destroyed. Among great difficulties the heavy painted cross, drenched with water, was brought down and laid in a horizontal position. It took six hours to accomplish this difficult task, while the flakes of colour detached and fell in the mud. The mud was sieved and some fragments were recovered.

The statue of Dante, now in front of the church, was still in the middle of the piazza in 1966.

Specific collections affected in Florence were the Archives of the Opera del Duomo (Archivio di Opera del Duomo), 6,000 volumes/documents and 55 illuminated manuscripts were damaged; Gabinetto Vieusseux Library (Biblioteca del Gabinetto Vieusseux): All 250,000 volumes were damaged, namely titles of romantic literature and Risorgimento history; submerged in water, they became swollen and distorted. Pages, separated from their text blocks, were found pressed upon the walls and ceiling of the building; the National Library Centers of Florence (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale Firenze): Located alongside the Arno River, the National Library was cut off from the rest of the city by the flood. 1,300,000 items (or one-third of their holdings) were damaged, including prints, maps, posters, newspapers and a majority of works in the Palatine and Magliabechi collections.

and the State Archives (Archivio di Stato): Roughly 40% of the collection was damaged, including property and financial records; birth, marriage and death records; judicial and administrative documents; and police records, among others.

|

|

Santa Croce after the Florence Flood, Santa Croce after the Florence Flood,

4th of november 1966

|

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia, with a unique private swimming pool

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early morning light at the private swimming pool at Podere Santa Pia

|

|

Reflections on the private swimming pool at Podere Santa Pi

|

|

Evenings around the pool in Tuscany offer a totally different quality of light and amazing colors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monte Christo. Situated in panoramic position, overlooking vineyards and olive trees, Santa Pia features incredible sunsets...

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|