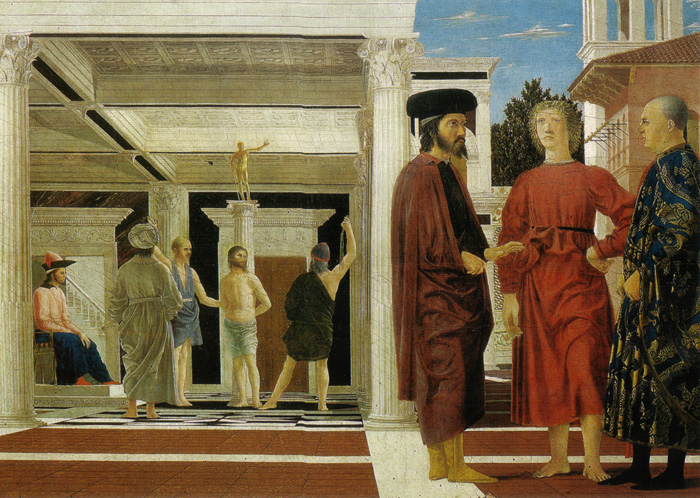

Renaissance painting differed from the painting of the Late Medieval period in its emphasis upon the close observation of nature, particularly with regards to human anatomy, and the application of scientific principles to the use of perspective and light. The Flagellation of Christ by Piero della Francesca demonstrates in a single small work many of the themes of Italian Renaissance painting, both in terms of compositional elements and subject matter. Immediately apparent is Piero's mastery of perspective and light. The architectural elements, including the tiled floor which becomes more complex around the central action, combine to create two spaces. The inner space is lit by an unseen light source to which Jesus looks. Its exact location can be pinpointed mathematically by an analysis of the diffusion and the angle of the shadows on the coffered ceiling. The three figures who are standing outside are lit from a different angle, from both daylight and light reflected from the pavement and buildings.

The religious theme is tied to the present. The ruler is a portrait of the visiting Emperor of Byzantium.[1] Flagellation is also called "scourging". The term "scourge" was applied to the plague. Outside stand three men representing those who buried the body of Christ. The two older, Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathaea, are believed to be portraits of men who recently lost their sons, one of them to plague. The third man is the young disciple John, and is perhaps a portrait of one of the sons, or else represents both of them in a single idealised figure, coinciding with the manner in which Piero painted angels.

The Flagellation of Christ (probably 1455–1460) is a painting by Piero della Francesca in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino. Much of Piero's later career was spent working at the humanist court of Federico da Montefeltro at Urbino. There he painted the portraits of Federico and his wife (Uffizi, Florence, c. 1465) and the celebrated Flagellation (still at Urbino, in the Ducal Palace). The Flagellation is his most enigmatic work, and it has called forth varied interpretations. Gombrich has suggested that the subject is rather The Repentance of Judas and Pope-Hennessy that it is The Dream of St Jerome.

Called by one writer an "enigmatic little painting," the composition is complex and unusual, and its iconography has been the subject of widely differing theories. Kenneth Clark placed The Flagellation in his personal list of the best ten paintings, calling it 'the greatest small painting in the world'.

The flagellation is a recurring motif in Christian art which depicts a scene from the passion of Christ. Traditionally, this setting features Jesus tied to a column while being flayed with a scourge or whip. In Francesca's portrayal of this event, however, the main focus is not on the flaying but on a grouping of three men who stand in the right foreground. Their identitites are not known though studies of the work have yielded several possibilities. Their relationship to the tragic event in the background is also not clear.

There is no documentation of who commissioned this artwork or the location of the commission. The creation date is only an approximation. The piece is small, a modest 23 x 32 inches, which supports the possibility that the painting was meant for private use. Earliest commentary on the piece suggests that the aim of the patron was to keep the true intention of the work enigmatic. Absent valid documentation, the patron, the identity of the foreground trio and the purpose of the painting remains a mystery.

Description

The theme of the picture is the Flagellation of Christ by the Romans during his Passion. The biblical event takes place in an open gallery in the near distance, while three figures in the foreground on the right-hand side apparently pay no attention to the event unfolding behind them. The panel is much admired for its use of linear perspective and the air of stillness that pervades the work, and it has been given the epithet "the Greatest Small Painting in the World".[2]

The painting is signed under the seated emperor OPVS PETRI DE BVRGO S[AN]C[T]I SEPVLCRI – "the work of Piero of Borgo Santo Sepolcro" (his native town).

The Flagellation is particularly admired for the mathematical unity of the composition, and Piero's ability to depict the distance between the actual flagellation scene and the three characters in the foreground realistically through perspective. The portrait of the bearded man on the left is considered unusually intense for Piero's time.

Interpretations

Much of the scholarly debate surrounding the work concerns the identities or significance of the three men in the right foreground, and of the sitting man on the left, who is in one sense certainly Pontius Pilate, a traditional element in the subject, but may also represent a contemporary figure.

It has also been suggested that there can be multiple identities for each man depending on how it is read. The interior scene is illuminated from the right while the "modern" outdoor scene is illuminated from the left. Originally the painting had a frame on which the Latin phrase "Convenerunt in Unum" ("They came together"), taken from Psalm 2, ii in the Old Testament, was inscribed.

Conventional

According to the traditional interpretation, the three men would be Oddantonio da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, Piero's patron, and his two advisors Serafini and Ricciarelli (who allegedly murdered the Duke on July 22, 1444). The two advisors are identified also as Manfredo dei Pio and Tommaso di Guido dell'Agnello, who were also allegedly responsible for Oddantonio's death due to their unpopular government, which led to the conspiracy. Oddantonio's death would be compared, in its innocence, to that of Christ.

Dynastic

Another traditional view considers the picture a dynastic celebration commissioned by Duke Federico da Montefeltro, Oddantonio's successor and half-brother. The three men would simply be his predecessors. This interpretation is backed by a 18th century document in the Urbino Cathedral, where once the painting was housed, and in which the work is described as "The Flagellation of Our Lord Jesus Christ, with the Figures and the Portraits of Duke Guidubaldo and Oddo Antonio".

Political-theological

According to this other old-fashioned view, the figure in the middle would represent an angel, flanked by the Latin and the Orthodox Churches, whose division created strife in the whole of Christendom.

The seated man on the far left watching the flagellation would be the Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaiologos, as identified by his clothing, particularly the unusual red hat with upturned brims which is present in a medal by Pisanello. In the variant of this interpretation, proposed by Carlo Ginzburg in 2000[3], the painting would be in fact an invitation by Cardinal Bessarion and the humanist Giovanni Bacci to Federico da Montefeltro to take part in the crusade. The young man would be Bonconte II da Montefeltro, who died of plague in 1458. In this way, the sufferings of Christ are paired both to those of the Byzantines and of Bonconte.

Silvia Ronchey and other art historians[4] agree on the panel being a political message by Cardinal Bessarion, in which the flagellated Christ would represent the suffering of Constantinople, then besieged by the Ottomans, as well as the whole Christianity. The figure on the left watching would be sultan Murad II, with John VIII on his left. The three men on the right are identified as, from left: Cardinal Bessarion, Thomas Palaiologos (John VIII's brother, portrayed barefoot as, being not an emperor, he could not wear the purple shoes with which Constantine is instead shown) and Niccolò III d'Este, host of the council of Mantua after its move to his lordship of Ferrara.

Piero della Francesca painted the Flagellation some 20 years after the fall of Constantinople. But, at the time, allegories of that event and of the presence of Byzantine figures in Italian politics were not uncommon, as shown by Benozzo Gozzoli's contemporary Magi Chapel in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence.

Kenneth Clark

In 1951, the art historian Kenneth Clark identified the bearded figure as a Greek scholar, and the painting as an allegory of the suffering of the Church after the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, and of the proposed crusade supported by Pope Pius II and discussed at the Council of Mantua. Again, the man in the far left would be the Byzantine Emperor.

Marilyn Aronberg Lavin

Another explanation of the painting is offered by Marilyn Aronberg Lavin in Piero della Francesca: The Flagellation[5].

The interior scene represents Pontius Pilate showing Herod with his back turned, because the scene closely resembles numerous other depictions of the flagellation that Piero would have known.

Lavin identifies the figure on the right as Ludovico Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, and the figure on the left as his close friend, the astrologer Ottavio Ubaldini della Carda, who lived in the Ducal Palace. Ottavio is dressed in the traditional garb of an astrologer, even down to his forked beard. At the time the painting is thought to have been made, both Ottavio and Ludovico had recently lost beloved sons, represented by the youthful figure between them. Note that the youth's head is framed by a laurel tree, representing glory. Lavin suggests that the painting is intended to compare the suffering of Christ with the grief of the two fathers. She suggests that the painting was commissioned by Ottavio for his private chapel, the Cappella del Perdono, which is in the Ducal Palace at Urbino and which has an altar whose facade is the exact size of the painting. If the painting was on the altar, the perspective in the painting would have appeared correct only to someone kneeling before it.

David A. King

In a recent book,[6] a new interpretation developed by David King, director of the Institute for the History of Science in Frankfurt, Germany, is presented, which establishes a parallel between the painting and the inscription on an astrolabe made in 1462 by Regiomontanus and presented to Cardinal Bessarion.[7] King claims that by searching for monograms of names across the epigram one can establish the dual or multiple identities of each of the eight persons and one classical god in the painting. The young man in red is the eager young German astronomer Regiomontanus, the new protégé of the Cardinal Bessarion. However, his image embodies three brilliant young men close to Bessarion who had recently died: Buonconte da Montefeltro, Bernardino Ubaldini dalla Carda and Vangelista Gonzaga. One of the purposes of the painting was to signify hope for the future in the arrival of the young astronomer into Bessarion circle as well as to pay homage to the three dead young men.

Sir John Pope-Hennessy, the art historian, argued in his book The Piero della Francesca Trail that the actual subject of the painting is "The Dream of St. Jerome." According to Pope-Hennessy,"'As a young man St Jerome dreamt that he was flayed on divine order for reading pagan texts, and he himself later recounted this dream, in a celebrated letter to Eustochium, in terms that exactly correspond with the left-hand side of the Urbino panel."

Pope-Hennessy also cites and reproduces an earlier picture by Sienese painter Matteo di Giovanni, which deals with the subject recorded in Jerome's letter, helping to validate his identification of Piero's theme.

Influence

The painting's restraint and formal purity strongly appealed when Piero was first "discovered," especially to admirers of cubist and abstract art. It has been held in especially high regard by art historians, with Frederick Hartt describing it as Piero's "most nearly perfect achievement and the ultimate realisation of the ideals of the second Renaissance period".

|

![]()